Quiz games. They’re one of the most basic forms of game out there, going a long, long way back to the days of game shows on radio and television, persisting to this very day. They’ve also been a part of videogaming from the early days: as soon as ROM chips could feasibly hold a decent amount of text, quiz games started to appear in arcades and on consoles.

Nowadays, when you think of arcade quiz games, you probably think of something like the multiplayer setups you see at trivia nights in a local bar. This is the direction Western quiz games evolved in: they never really eschewed a game-show/board-game style format, and evolved to implement either real-money gambling mechanics or large-scale multiplayer, competitive functionality.

In Japan, however, things played out very differently. Arcade quiz games started to appear there in the mid-late 80s, through companies like Sega and Nichibutsu. As the 90s came along, a renaissance of quiz-game development created a unique, fascinating genre with an abundance of different thematic elements.

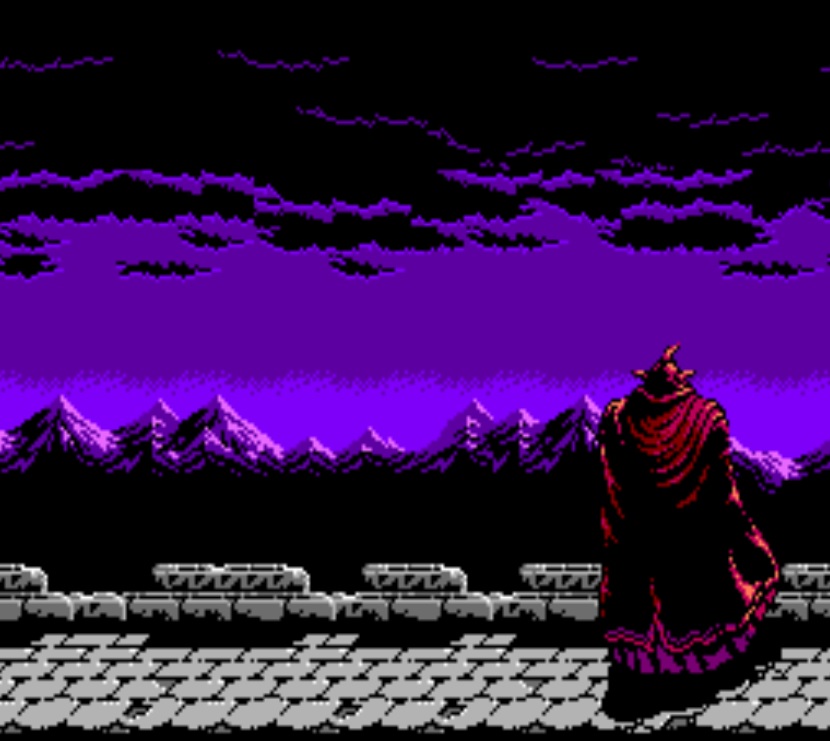

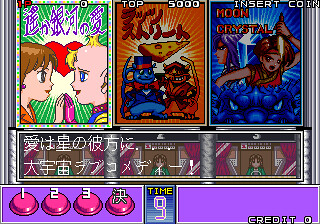

The genre first saw significant advancement through games like Adventure Quiz: Capcom World, a trivia game loaded with 80s Capcom fanservice, and Mitchell’s Quiz Sangokushi, which melded the question-and-answer format with strategic, territory-conquering gameplay. These games utilized elements of visual novels and strategy games to make the quiz experience more appealing and engaging. Other games put quiz elements into fun new genres: Taito’s Quiz Chikyuu Boueigun (“Quiz Earth Defense Force,” no relation to the current Earth Defense Force games by D3 Publisher) has you saving the planet in a story that’s chock-full of classic sci-fi parodies, while SNK’s Quiz Daisousasen (“Quiz Big Criminal Investigation”) is a detective story that morphs into a weird sci-fi/horror thing at the end. You still had game-show style quiz games too, but they were quickly losing ground to more ambitious efforts.

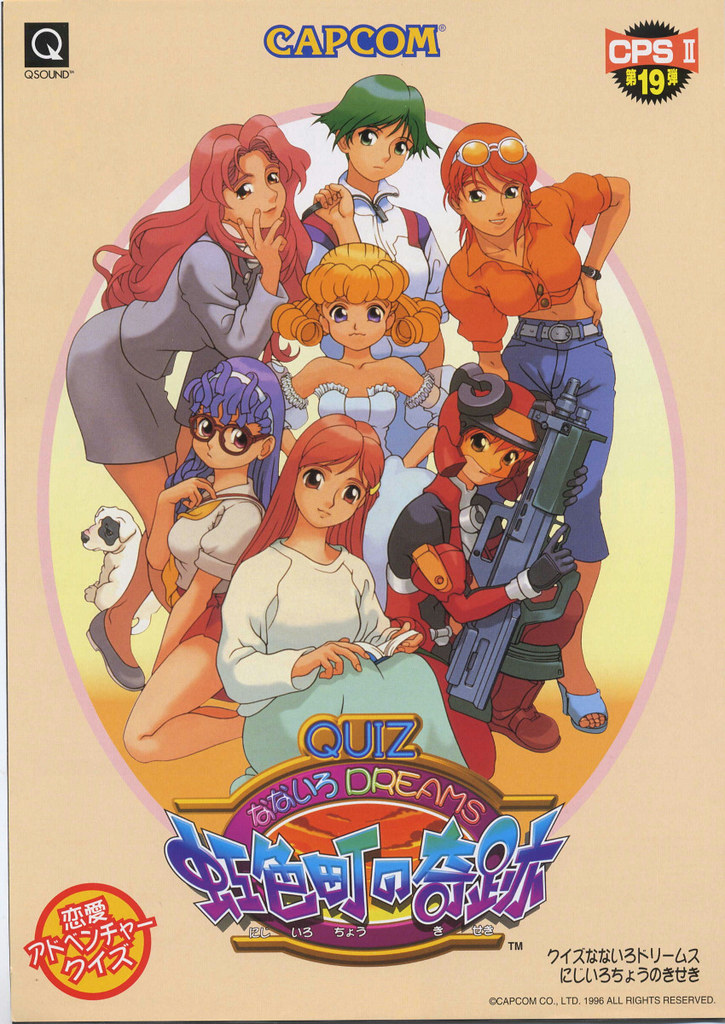

In some cases, publishers adapted existing properties but added a quiz-game twist, hoping the familiar name would draw in customers. This is how we got games like Saurus’s Quiz King of Fighters and Taito’s Quiz HQ, which combined existing game properties with a quiz-game element. As time passed, however, more and more experimentation happened. The mid-late 90s were really a golden age for arcade quiz games, resulting in a stunning variety of thematic and gameplay genres mixing in with traditional quiz elements.

Interestingly, quiz games tend to be very lengthy, sometimes taking an hour or more to complete from start to finish… which, in theory, goes against the short, focused play experiences arcades want to offer. You want to get people off that machine as quickly as possible, right? However, with these new thematic ideas, players became more committed to seeing the games through to the end. It doesn’t hurt as much to abandon a gameshow you feel like you’re not doing well in, but when you’re in the middle of a story about saving the universe? Hell yes you’re going to brute-force your way through with yen! Add a second player into the mix and watch earnings double!

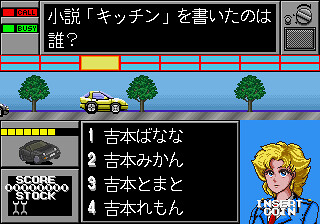

Unfortunately, most the appeal of these games is lost on the West. Japanese quiz games might be the most culturally impenetrable games out there: not only do you have to be fluent in the language, you also have to be fluent in a variety of cultural elements. Sure, you might know the multiple readings of thousands and thousands of kanji, but unless you lived in Japan during the early 1990s and remember which popular talent of the time appeared in a specific ad campaign, you’re probably not going to get very far. That is, unless you cheat. Thankfully, emulating most of these games allows you to cheat through the quiz portions, making the games somewhat more accessible… though it does result in the game losing a big part of its inherent charm. (Plus, even if you do cheat, if you don’t speak the language you can find yourself making very poor choices.)

You don’t hear a lot about quiz games nowadays — the genre saw a sharp decline in development and interest after the 1990s. Currently, the big name (and basically the only name) in Japanese quiz games is Konami’s Harry Potter-inspired Quiz Magic Academy, which has a new arcade version releasing soon (along with a mobile version that is no doubt raking in plenty of money). Right now, it’s practically the only arcade quiz game in town, unless your local game center has an older game installed in a cabinet somewhere.

But where does someone who doesn’t know anything about Japanese arcade quiz games go to get a good sampling of what the genre has to offer? Well, that’s why I’ve taken the time to write this. Today, we’re going to take a look at some noteworthy Japanese-style arcade quiz games: One that, against all odds, got a localized release, and three others that showcase some very interesting experiences. Continue reading