Guys. GUYS. Did you see that list ranking all of the Mario games? Holy crap! New Super Mario Bros. U at number one, for reals??? Why, clearly this is a horrible judgement that I must take to the internet to express my displeasure over– oh, no, wait, everybody else has already done that. Dangit!

But… hmm. This list has generated a lot of attention and discussion. Clearly, Gaming Dot Moe needs a real kick in the pants, an article that will drive vistors to the site in droves and make them read about Raimais and spur heated debate and conversation! We need to make a ranking list involving a popular, long-running videogame character!

Let’s see… Mario’s been done… Sonic? Oh jeez, that’s a debate I don’t even want to wade into, what with the differences between Classic and Modern Sonic… I mean, hell, even if we just limited it to Modern Sonic, nobody can agree which ones are actually the good games and they will hate you for whatever you say! Megaman? I mean, that’s pretty cut-and-dry, the debate is basically between 2, 3, and X.

Wait… I’ve got it!

Yes! Pac-Man! Nobody’s done a comprehensive list talking about the best Pac-Man games yet! We’re going to have another GAMING DOT MOE EXCLUSIVE on our hands here!

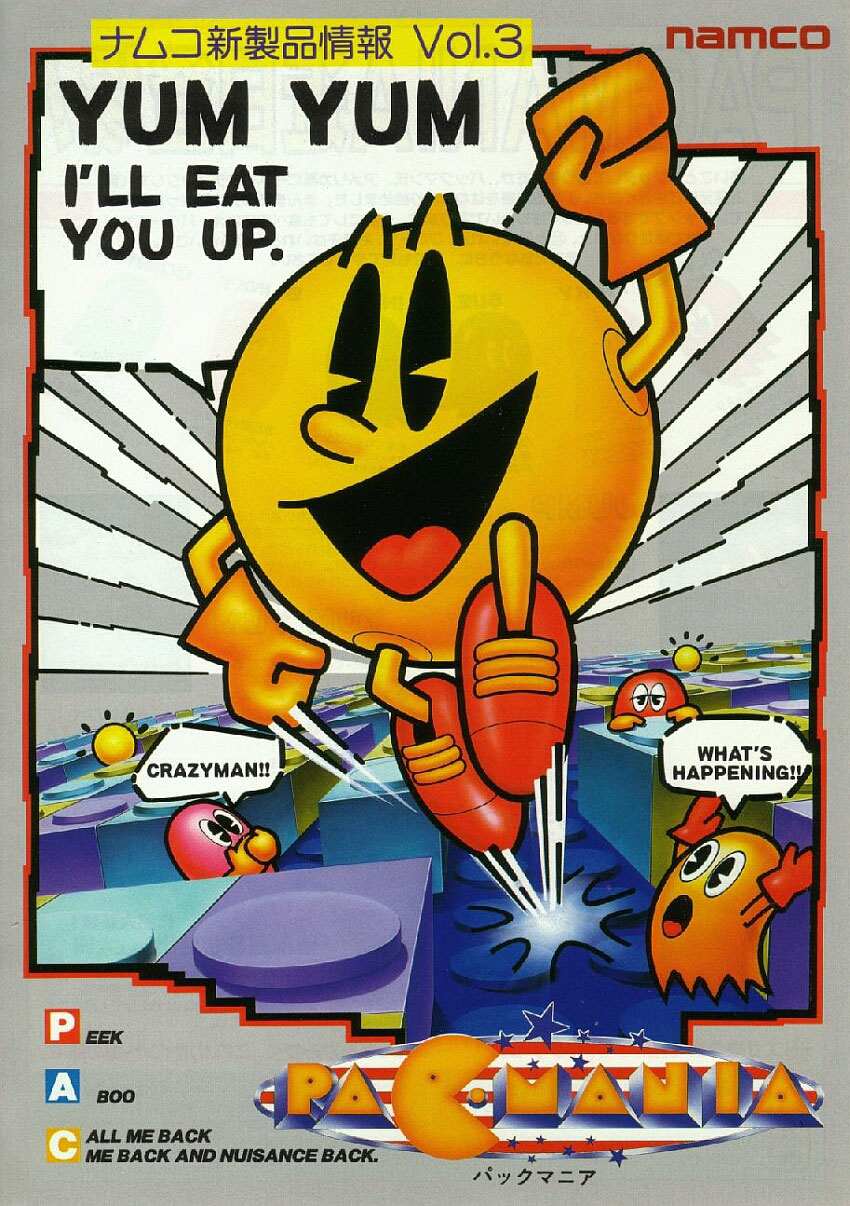

But lay something down first, because there’s a lot of Pac-Man games out there covering different genres. The main rule in this ranking is that the game has to adhere to the basic tenets of classic Pac-Man gameplay, which means roaming mazes while collecting objects. So no, no Pac-Man World, Ghostly Adventures, Pac-Attack, or Pac-Land. Sorry if you’re looking to see if Pac-Man Party is better or worse than Pac-In-Time, but someone else will have to make that list.

That doesn’t mean we can’t talk about a few other Pac-Man games first, though…

Special Mentions

Pac-Man 2: The New Adventures

Out of all the games Pac-Man’s ever starred in, this one deviates the furthest from the concepts established in the original, meaning that there’s no way I’d put it on the list with the rules I established. However, it’s worth mentioning because it’s a game you simply have to experience, preferably vicariously.

It feels like somebody at Namco woke up one day and said, “Hey, we have a beloved videogame icon here, but the style of game he pioneered is just too old for the purple-stuff addled kids of the 90s. We need to make something unique and original to make Pac hip and relevant again!”

And the result was… a point and click adventure game. No, scratch that — it’s a point and click adventure game with an added layer of obfuscation. Pac-Man is not under your direct control — instead, you have a slingshot to hit objects (and Pac-Man) with and the ability to yell “LOOK!” in the hopes that you can direct his attention somewhere. Unfortunately, Pac-Man rarely does what you actually want him to do, resulting in amazing moments of frustrating as Pac-Man winds up in stupid, stupid situations that would have been wholly avoidable if you could just tell him what to do. This is where the “smug asshole Pac” meme began, and once you see the game, you’ll understand why.

I wouldn’t recommend trying to play this yourself, but you absolutely should watch somebody else suffer through trying to get Pac-Man to do very simple tasks. It’s a good time for everyone… except the player.

https://twitter.com/TieTuesdayLP/status/933544071880065025

Pac-Man Battle Royale

This one’s tough to slide into the list just because how much fun you get from it is wholly dependent on how many players you have. If you have a full group of four people, then yes, this is going to be one hell of a time. However, with every player you subtract, Battle Royale becomes noticeably less enjoyable. It doesn’t really seem fair to fault an inherently multiplayer game for being less fun with less players, so I’m going to exclude this one from the ranking.

Anyhow, that’s enough preamble, let’s get to

THE RANKINGS

Continue reading →