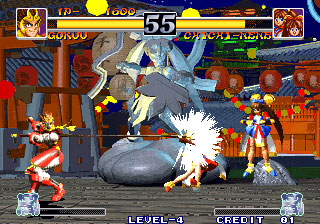

I don’t know why, but I’ve always been strangely fascinated by Ragnagard. It feels like such an anomaly in the Neo Geo’s massive library of fighting games on numerous levels: the CG visuals, the slow-feeling gameplay, the focus on aerial combos. It’s the sort of game that I’ve felt a compulsion to research, to figure out just how it came into being.

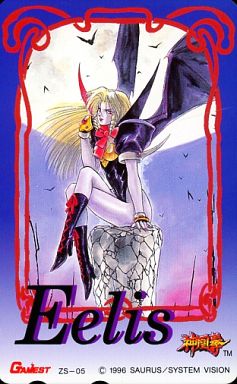

I’m the sort of person who will delve into weird internet rabbit holes over the course of researching stuff and pursuing information, and sometimes that yields incredibly interesting results. One day, when I was out looking for things related to Ragnagard on Japanese sites, I came across a page that had a gorgeous illustration of the game’s main female lead, Benten. But that’s not all that was there: alongside it were numerous anecdotes written by someone who was clearly heavily involved in the game’s development. It turned out this site was run by one Powerudon, an accomplished artist in the game industry who had been one of the driving forces behind Ragnagard’s development.

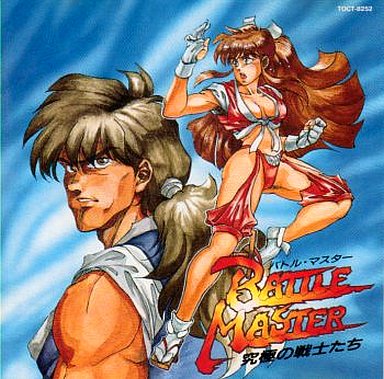

Looking around his site yielded more interesting tidbits of info, particularly related to a Super Famicom fighting game called The Battle Master. It hadn’t hit me that this and Ragnagard were done by the same developer, as they have a dramatically different feel, but Powerudon had laid out a lot of details about the mechanics and development of these titles on their site — alongside some incredible artwork

I knew I had to talk with Powerudon. One of the reasons I created gaming.moe is to preserve elements of gaming history that might otherwise be lost to time, particularly the words and memories of the people behind games both well-known and obscure. I reached out to Powerudon for an interview, and he agreed, so I emailed him a batch of questions.

A while later, he sent me a massive text file containing replies to all of the questions I had sent. I had asked him to go into as much detail as possible, and he did just that — for which I’m extremely grateful, because he has some really interesting anecdotes and thoughts on game development. So sit back, grab a drink, and enjoy a lengthy interview about System Vision, Battle Master, Ragnagard, and the tumultuous environment of game development in the early/mid-90s.

Special thanks to Tom James and Jason Moses for translation assistance!

Thank you for taking the time for this interview. Can you tell us a little bit about who you are, your background, and your current line of work?

I go by the name POWERUDON online. There’s a food in Japan that people refer to as “Chikara Udon,” and, since “chikara” means “power” in English, I just did a little switchover to end up with my current nickname. I love weird names, you see. I’m listed as HIROAKI FUJIMOTO in the staff credits for Battle Master and Ragnagard. My real name is Akihiro Takanami.

I’m currently Design Chief over at h.a.n.d. Inc. It’s no problem naming titles I’ve worked on, and while it was a few years ago, a major project in my resume is the smartphone game “The World Ends With You: Solo Remix”, which I handled general graphics work on. The job required converting all of the pixel graphics in the game to high resolution, and the biggest chunk I handled was enemy animations.

My name shows up in the game’s opening movie (around the 9:18 mark):

My parents divorced when I was young. After that, I spent a number of years living back and forth between my mom and dad. I was in high school at the time. My dad was living on his own, but mom remarried, and my stepfather’s last name was Fujimoto, and that’s what I ended up going with after I graduated and got a job.

My stepfather, Fujimoto, was an official in the Self-Defense Forces. After I graduated, my mom told me that if I got a job in the SDF, I’d be able to leave work at 5 every day and have plenty of time to do what I wanted. I tried it, and it was nothing like that at all, and before you knew it all I could think about was getting back to working on manga and game art as soon as possible. After my training ended, I was assigned to an artillery squad, and despite some difficulties managed to leave the position.

One of the conditions for joining the SDF was using Fujimoto as my name instead of Takanami. I used Fujimoto from the time I joined/quit the SDF up until I left System Vision. And that’s why I’m listed as HIROAKI FUJIMOTO in the staff rolls.

When did you become interested in pursuing a career in the game industry?

I first became aware that the “game industry” existed when I was in high school. My dream for all of my elementary and middle-school years was to become a manga artist, and hadn’t so much as considered the game industry. I was always penciling comics in my notebook and showing them to friends, and played games in the arcade (and at home after the Famicom came out) and enjoyed them simply as a player.

When I was in elementary school, my game experience made me a big fan of computers, and I had the chance to use a PC known as the MZ1500 by Sharp. This was probably one of the foundational moments that led to me joining the game industry. A friend of mine at school named Kikuo bought an MZ1500 — today he works as a programmer. (He also participated on Battle Master’s development as a programmer, incidentally). He let me come over on weekends and afternoons, where I’d use a pixel art tool called PCG Editor to draw pictures. When I couldn’t go to Kikuo’s house, I’d draw pixel art using graph paper instead.

Kikuo occasionally made small games, which he had me play. I basically learned the process for creating games thanks to him.

We had a lot of fun times with that MZ1500, but I ended up having to move after my parents changed jobs. It may have only been for a short time, but I’d been blessed with the opportunity to create something with computers.

==============================

Today, Kikuo runs a browser-game site called Collepic. Here’s his twitter.

I was actually involved with character and graphic design on the site. Before its current state as a browser game portal, Collepic was a separate social game you installed that allowed you to create pixel art to earn in-game currency that you could use to play games (the pixel art tool is still on the main site).

==============================

Things got a little rocky at home during my high school years. *laughs* As a result, I ended up leaving and living in a dorm. I was pretty free living on my own, so I ended up really going deep on games, partaking in the Super Famicom, Megadrive, and PC Engine. I was blown away by how much more powerful the Megadrive and Super Famicom were on release. “I can play games that look as good as the ones in the arcade!”

I really liked arcade games, but I lived in the middle of nowhere and had to make do with what little money I made from my newspaper delivery route. If I went to an arcade, I only had enough money to play a few times — the rest had to go to my bus fare home. But compared to what you could play at home, arcade games were still so far ahead of the curve that just looking at the screen was satisfying and enjoyable.

One day, I was talking with Kikuo on a long-distance phone call (smartphones didn’t exist back then), and he told me about a computer that could deliver graphics on par with the arcades. It was called the MSX2+, it was made by Sanyo, and it plugged into your TV. I got my hands on one and tried making games with it using the shooting game toolkit “Yoshida Kensetsu” and the RPG makers “Dante” and “Dante 2”. I never finished anything, though. (laughs)

For pixel art, I used “DD Club” and “Graph Saurus”. I hadn’t been able to experience game development since the MZ1500, and I spent those free days creating things all day long. But I still hadn’t considered the idea of entering the game industry.

What changed everything for me was the release of Capcom’s Final Fight on the Super Famicom. That was a greater shock to my system than Mario, F-Zero, or any RPG.

First, I loved creating characters. Before Final Fight, the characters in action games – particularly home console ones – were more symbolic representations than anything. But Final Fight’s Cody, Guy, Haggar, and all the enemies were like beautifully animated illustrations. It felt good to hit them and knock them down in droves, too. The gameplay and expressive power of the game shocked me into finally realizing that I might want to enter the game industry.

I encountered the MZ1500 in elementary school and the MSX2+ in high school, and I enjoyed using computers in general. Because I had that foundation, it only took one game to fill me with determination. I’d wanted to become a manga artist since I was a kid, but the dam holding back my resolve to make games broke under the pressure.

From there, I graduated high school, joined the SDF, and quit soon afterwards. I had no idea how to enter the game industry, and worried endlessly while working a bunch of part-time jobs, eventually ending up as a waiter at a golf course. The reason I quit the SDF without making any plans was out of an unusual fear I felt: that the creative side of me that wanted to make things would vanish being in that environment. Better to work part-time while creating pixel art on the MSX, and drawing in my notebook.

My living situation wasn’t great either. Creating things was basically the only thing keeping me grounded during this period of uncertainty.

When I was working as a waiter, one of my coworkers handed me the classifieds and said “Hey Fujimoto, this sounds up your alley, doesn’t it?” It was a wanted ad for an artist position at System Vision. At the time, it was pretty rare to see a position like that in Hokkaido. Hudson Soft had their main office here, but I assumed a famous developer like them would never accept somebody like me, and never considered them as a possibility. Afterwards, I found out that the internal situation at the company probably wouldn’t have allowed the development of original titles. If I had ended up joining Hudson, I don’t think I would have had the chance to make a fighting game.

My thought going into the interview at System Vision was that I might as well try applying, and if I got rejected, no big deal. But I wanted to draw sprites so bad, I would have been okay being stuck at the bottom rung of the company if it meant I could draw an enemy bullet for a shooting game. So I brought two of my sketch-filled notebooks and headed off to the interview. 15 minutes in, the person interviewing me looks at my notebooks and starts making comments about how much they wanted someone who could animate human movement, how useful it is that I can draw pixel art, and that they want me to come in starting next week. Honestly, I never imagined my sketches would ever get me a job, and even if I got rejected I would’ve been happy just seeing the inside of a game company. I also feel like I might have been saved by how generous the game industry was at the time, too.

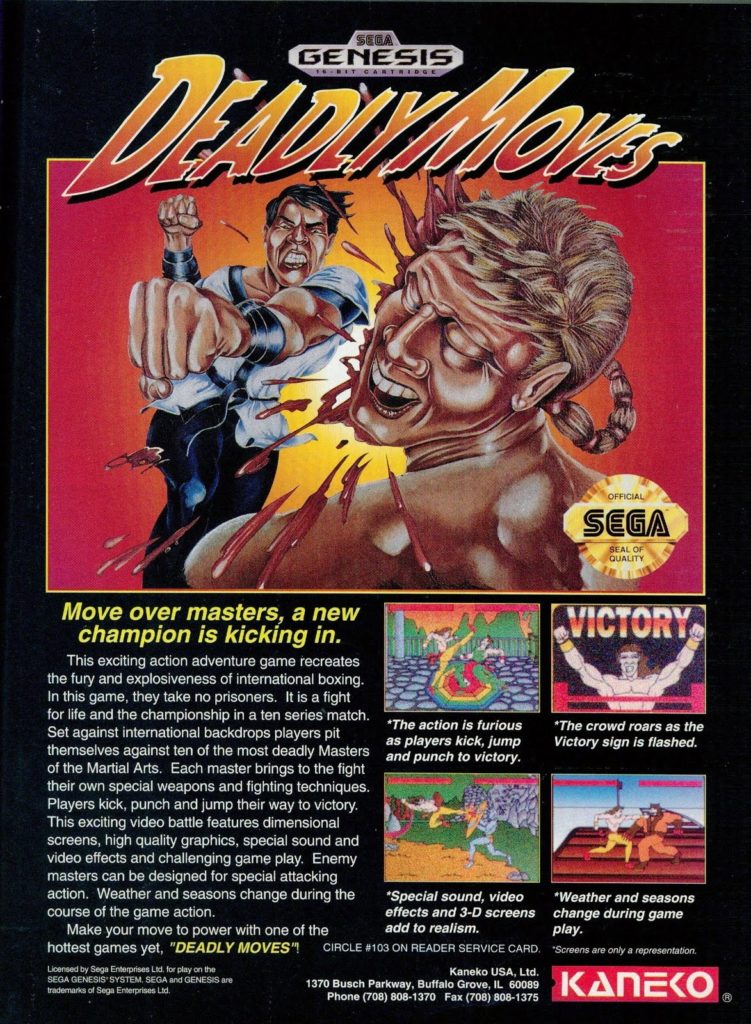

Somehow, Kaneko thought that not actually showing in-game screenshots was a good idea for the North American magazine ad

Can you talk about the development of Power Athlete (aka Deadly Moves/Power Moves)? Any interesting behind-the-scenes stories?

I’m putting this out there first, but considering I worked on the game, I’m about to lay out some disrespect. *laughs*

I was a total newcomer during the time we were working on Power Athlete, which I drew character sprite animations for. I never imagined in my wildest dreams that I’d be making sprites for a fighting game right after joining the company. After I quit the SDF and started working part-time jobs, the game that kept me going (and got me completely addicted) was Street Fighter II. Once I got the job at System Vision, I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw the materials for the game they were working on. “This is that fighting game Kaneko’s developing that I saw in Famitsu!”

Like I said before, I wanted to work on games, no matter how boring the job. I was completely ready to draw some enemy bullets. (laughs) But when the curtain was pulled back on what I was actually doing, it turned out to be a character design and animation job for one of my beloved fighting games. Human beings are quickly spoiled creatures, however, and as the job continued and I got used to how things worked at the company, I grew dissatisfied with Power Athlete’s game system. Well, maybe not spoiled. But from a player’s perspective it looked really boring.

The person who had thought up everything in the game was a Hudson veteran and programmer named Mr. S. I was still new, so I was in no position to voice my complaints. I asked him why the characters couldn’t duck, being able to move into and out of the background instead. “Hmm, to dodge hadokens and stuff by moving up and down, I guess?” he retorted with a chuckle. I’ll never forget how shocked I was at the way he responded so casually to those kinds of questions.

Street Fighter II was incredibly fun, and it seemed like tons of games were coming out that used the same format (the fact that Capcom allowed this and didn’t do anything to restrict development is amazing to me!). There must have been a lot of people who wanted to make a fighting game with every fiber of their being, so to see this guy’s attitude basically be all “the genre’s popular but I don’t really know anything about it or care,” and “I haven’t really thought too deeply about the systems or anything, but this is fine” was really disingenuous and hard to put up with.

There were people who wanted to make a fighting game so bad it hurt. When I think about how this guy had a golden opportunity handed to him on accident, wasted it, and made all the players — our customers — think “that sucked!” I’m more flabbergasted than angry. I couldn’t talk back as a new hire, and I didn’t have the vocabulary to come up with a new idea and smoothly communicate it to the publisher (KANEKO) in a convincing way. So I just humored him and said “Oh, I gotcha! So that’s the idea!” *laughs*

The game’s RPG mode was the same thing. They were just trying to cram RPG elements in there without really understanding what was fun about it, and the results were as boring as you’d expect.

As an aside, the prevailing opinion at the time was “keep otaku out of the game industry.” There were even features in game magazines at the time with pictures of clean cut young people next to disgusting slobs (read: otaku), with lots of idealized suggestions for what kind of people they were searching for. (Everyone’s probably forgotten that this ever happened…) It peaked around the transition between late Super NES-era/early Playstation, I think.

The kind of people they were looking for would generally sound like this:

“Do you know about board game X?”

“Sure don’t.”

“Have you seen anime Y?”

“Why would I watch anime?”

“What do you think makes game Z so interesting?”

“God, you’re such a nerd LOL”

Most of those people ended up valuing their free time more than games, thinking “that other job looks good” and leaving the industry.

“Caring a lot about games is uncool.” “It’s just a job, so don’t do anything you don’t have to.” “People who like games too much skew things and make everything screwed up.”

Those kinds of labels were everywhere. Mr. S was that time period and its opinions given form. What saved me was that he was a mild-mannered guy, not hateful at all. He just didn’t have any interest in games.

The thinking was that otaku were better able to handle specialized marketing research for this genre than regular people, and for a small company with limited staff, you had to make do with what you had. I’m not saying just being an otaku is important, though. You need to have a jumping-off point for thinking about things, for deciding “I want to make a game like this!”

For example, you might not be an otaku, but you can still say “I just don’t like this part about fighting games!” And that can open the way to a new kind of game. That kind of “core” is important to have. To me, people in the game industry like making games, so they’re going to push forward even if it’s rough. But I never even imagined that there would be guys with no interest in games working in the industry.

At the time, whether or not a game sold was all based on trends. And to land in a good place amongst the raging waves of public opinion was completely based on luck. Personal opinions on whether something is interesting or not, along with the actual players’ experiences determining whether a game jives with them or not is what constitutes “luck”. During this period, small companies didn’t do marketing research. There was no money or time to spare for it, and no effective way to conduct it, either. The only thing you could control from the creator’s side was your own attitude. The stance you take when you create something is evident in the finished work. If the creators enjoyed themselves and liked what they were doing, that excitement would show throughout in the finished game, and people would want to spend money on it. (Whether they actually know the game exists is another story.)

If people think “I hate this, so I’ll just do the bare minimum,” or “I’m tired and don’t want to fix anything” when they are making the game, that small amount of negativity is visible in-game and decreases the enjoyment of the experience for those playing accordingly. Even people who are dedicated to making something can’t reduce those negative factors completely, so you do your best to keep them to a minimum, but adult considerations like time and money result in issues here and there in the final product. Even if you make a game with love, problems will inevitably remain in places, which means that if your game is made by disinterested people, by people who hate their jobs, then the negative factors will simply compound upon themselves, resulting in truly astonishing kusoge.

On the other hand, if you think “all we have to do is spend a lot of time and it’ll be fine,” and waste a lot of your time, you might end up with an unfinished game and miss your chance to have a hit. If you become too rigid and fixated on sticking to a particular path, you can end up creating something hard and rigid that nobody else is capable of understanding. It takes a lot of money to market something, and you’re not getting that money back. Even this is a huge gamble. These are the things I’ve learned. I didn’t come to the above conclusions right after releasing a game, but by spending years wondering “how did things end up like that?” as a starting point and going from there.

When we sent Power Athlete off for mastering, I was baffled to hear my seniors talking about how far off from being finished the game actually was. I figured releasing finished games was normal. When I asked them about it though, they told me completely finished games practically don’t exist, and that the company had actually had a number of games that failed in the middle of development.

Power Athlete was originally being developed for the Mega Drive, but it also saw release on the SNES later. What kind of tools did you use for development on each platform? Were there large differences between them? Were there any difficulties when porting the game to the Super NES?

My understanding is it was the opposite. The game was originally developed for the SNES and got ported to the Mega Drive afterwards. My work on the port was changing the color palette of the protagonist’s wristband from red to blue. (I’m not sure if there was any meaning behind the change, but to the best of my knowledge, I think they just really wanted to differentiate it from the SNES version somehow.)

I might be mistaken about this or have some wrong information, but it probably had something to do with Kaneko’s overseas sales division since the Genesis was so popular outside Japan at the time. That’s just hypothesizing though.

The one dev tool I had direct contact with was hooked up to a CRT television for checking pixel graphics. I never touched anything related to Megadrive development and just left it up to the programmers.

The pixel art tool was an editor developed by a programmer named Hideki Suzuki. It ran on a PC9801 (I think?). It was called “Jinbaba”… Suzuki’s names could have used some work, but it was based on Hudson’s “PE” graphics tool and refined for ease-of-use.

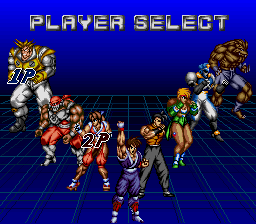

The next game after Power Athlete was Battle Master – Kyuukyoku no Senshitachi (The Ultimate Warriors). Why did System Vision decide to make another fighting game?

Mostly because we were dissatisfied with how Power Athlete turned out. We wanted to make things more interesting with the characters we’d been assigned, started throwing out ideas, and pretty soon we were basically planning a game. After Power Athlete finished and we started talking about doing a new project, the president invited us out to dinner and asked me what I wanted to do next. I immediately answered “a fighting game,” and the rest is history.

From planning, to characters, game design and the game systems themselves, you contributed a lot to Battle Master’s development. How did you handle such an incredible workload?

The biggest source of my taking on so much work was my not understanding how other companies made fighting games. *laughs* System Vision was a small company at the time, and we didn’t hire people to be planners exclusively. Artists and programmers wore a lot of hats.

I was really happy about Battle Master. I finally had the chance to make the fighting game I’d dreamed of, and I worked like a man possessed. I did planning, designed all the characters and plenty of other graphics besides. I poured energy into every facet of the game, and slept at the office during weekdays.

The most time-consuming work was thinking up moves for all the characters, and drawing everything out on copy paper so that it could get scanned in for pixel-graphics purposes later. Difficult, but fun. Drawing animation to my heart’s content started to put pressure on the amount of graphics memory we had available, so I also came up with a way to re-use graphics. Honestly, I referenced the SNES version of Street Fighter II a lot – it was practically a textbook to me. Sagat’s jump kick is reused for his crouching kick, E. Honda’s sweep is technically anatomically incorrect when flipped but looks fine in motion… examining that game gave me an idea of what would and wouldn’t work.

It wasn’t until about half a year after the completion of Battle Master that I realized the terrifying extent of my ignorance. Samurai Shodown and the new version of Fatal Fury had come out, and I finally got to take a close look at their staff rolls – which I’d never looked at that seriously when I was just a player – as a member of the industry. Imagine my surprise when I saw that each character had multiple staff members dedicated to their creation. There were tons of people in the credits for Street Fighter II, too…

From looking at the credits for famous games like the ones I mentioned above, it seemed like at least one person was in charge of making a single character, and the majority had two to three. When the same name appeared on multiple characters, I surmised that staff members who had finished work on one character would help out with others.

System Vision was the complete opposite. Three characters were made by one person. After characters were finished, the backgrounds were assigned to people three at a time. At Capcom, it seems like at least one person was in charge of every individual background. I’m pretty jealous that they were able to split up work like that. I had plenty of fun just drawing the pixel art, but the other two weren’t so lucky. *laughs*

I’d been drawing pixel art since I was in elementary school, but the other two guys were total newcomers. There was Mr. T, who had only been in the industry a year. Power Athlete was the first project he’d done pixel art for. The other guy was Mr. K, who started in high school, who also had never drawn pixel art before. To top it off, Battle Master was his first job working in game development. We got another guy on the team around the time development wrapped to help with the ending graphics, but he’d never worked in the industry before either and was a total pixel art beginner.

The main programmer was Hideki Suzuki, who I mentioned earlier. He was a veteran who developed the X68000 action game Genocide for a company called Zoom. He was really good at analyzing games and could clearly explain to you why SF2 was such an interesting game. I really looked up to him. There was also Kikuo, who handled side programming duties, and Mr. S, another programming veteran. Battle Master was developed by 6 people – an incredibly small team. Which also might explain why the game’s staff roll is so short. *laughs*

Despite this, Battle Master managed to hit #7 on the Famitsu sales rankings. I never dreamed of making it up there, not even for a moment.

My ignorance of how other companies do things resulted in us creating a very Street Fighter II-esque game on a remarkably small budget.

A short time after Battle Master came out, the head of the company built a new house with a huge garden attached. All I got was a single 200,000 yen bonus. *laughs*

Unlike other fighting games of the era, Battle Master’s rounds move really quickly, with easily-executed attack chains and dash-like movement options that only really started to show up in fighting games toward the end of the 1990s. Where did these mechanics come from, and why did you decide to put them in the game?

Something that was always unsatisfying to me when playing SF2 was the inability to move instantly from defending to attacking. Granted, part of that might just because I played the game so much that I got used to it. But that’s what inspired the defensive options. Another thing that bothered me was that I felt burdened with a lack of attack options when playing against others in SF2. But people who loved playing matches didn’t have a problem with this. So who did?

Jump cancelable moves are fun, but until SF2 Turbo came out jump arcs were so slow that you were just asking to get anti-aired. The result was that players came up with little tricks to augment their offense. They’d use light dragon punches and light tatsumakis to move forward slightly while still putting out a hitbox, or use rapid light attacks and fireballs to restrict the opponent’s movement while slowly drawing closer. They’d create little tricks to work into their spacing and offense, or leave intentional gaps by whiffing moves. It’s an incredible testament to SF2’s depth that the players had such a base for their ingenuity. However, for people who had never played the game before, these little “tricks” looked like a barrage of utterly meaningless nonsense. Not being able to include them would be an issue too, though.

With that thinking in mind, these were my 3 goals for Battle Master’s system:

- Including a lot of ways to engage in offense (with new players in mind).

- Making the game look like the kind of fierce battle scenes you’d see in anime and manga.

- Work in some of the basics from actual martial arts.

Here’s how all that shook out.

- Game mechanics

Jump fall speeds are fast, as are dashes.

Air blocking allows you to jump in on opponents. (Battle Master only lets you block on the way down from a jump.)

Special moves cause you to move forward quickly, and there are cancelable specials as well to give you a chance to counterattack. Beyond that, I just liked them because they felt good to do.

All of these were included with new players in mind, but I also imagined that more advanced players would provide the means for players to create new kinds of offense.

- Presentation

The manga originator of hi-speed battle action is Dragon Ball, but what inspired Akira Toriyama was probably Jackie Chan’s movies. His interplay of attack and defense is almost certainly what led to the way Goku fought in those battle scenes. All of those influences – manga, anime, and live-action moves – served as inspirations. Being able to dash in close with a flurry of strikes means that you could see certain scenes in manga and anime and recreate them in-game.

- Implementing Ideas from Real Martial Arts

I practiced Shorinji Kenpo from elementary school up until I started working. The fundamentals of Shorinji Kenpo are to “attack at the same time you defend an opponent’s strike.” That’s what gave me the idea for Guard Cancels.

I designed the inputs to be difficult – you had to be clean or moves wouldn’t come out. Even if your inputs were bad, though, you could do special moves by moving the pad around a lot and pressing buttons. (If I was making the game now, I’d make the inputs simple and implement a meter system like in Street Fighter Alpha…)

To save on space, Battle Master doesn’t have a lot of hit effects, but we still wanted some really crazy-looking moves, so we included a lot of chain specials similar to Raijinken and Fujinkyaku. The counterattack from guard cancelling could often punish both regular chains as well as these special moves if you blocked them successfully. I tried to strike a balance for both new and advanced players. To beat guard cancels, I also included elements like being able to cancel certain specials into other specials.

Reversing throws on opponents is an idea that came from Aikido, which is all about reversing the momentum of your opponent’s attacks. “Nage ukemi” is another real life martial art technique whereby you neutralize the force of the opponent’s throw to land safely. But in fighting games, there were no ways to defend against an opponent’s throw.

One of the benefits of fighting games as a format is that a certain amount of experience from one game carries over to another, and new players can use systems that are unfamiliar to more experienced players to have a fighting chance. Advanced players, meanwhile, can enjoy thinking of ways to use those systems in new and unexplored ways. That’s the ideal, anyway. I didn’t want to make it so that advanced players could lose to beginners. My goal was to give the losing side a fighting chance, and plenty of options when battling others. But it simply wouldn’t make sense to make beginners stronger than experts.

System Vision’s president wanted to try doing a release on Neo Geo, but SNK declined, saying that they weren’t interested in third-parties, and we unfortunately had to go with a home console release. The reason this bummed me out is that (at the time – ed), unlike arcade games, console-only fighting games had no chance of going mainstream. On the other hand, we didn’t have to deal with the pressure that comes from having to make a game robust enough to serve as a means of competition, and could just kick loose during development.

But then there’s the issue of no stun happening after a rush move… That’s just a bug we forgot to fix. Granted, it was Suzuki who forgot. *laughs* There’s no way we’d release the game with a bug like that – or so I assumed – and never even bothered contacting Suzuki to remind him. It was both our faults. I’m really sorry! When you meet up to play with others, please make some house rules to balance things out! *laughs*

The game had a really unique sci-fi setting. What kind of influences inspired you when you were working on the character and stage designs?

It’s not like I was ever trying to hide it or anything, but I love the work of Masamune Shirow, Yukito Kishiro, Akira Toriyama, and sci-fi in general. SF2 has an incredibly deep concept and the brains of Nishitani and Akiman behind it – we couldn’t compete head on. I lightened up some of the darker elements of the stuff I was drawing from and came up with a lighter sci-fi action setting. The reason for a fantasy character like Wulvan appearing in the game’s futuristic world was all because of Dragon Ball. And of course, there are actual aliens like Body and Zeno.

Thanks to the impact of SF2, Kaneko and Toshiba EMI both thought fighting games meant “serious atmosphere” and “gritty characters,” and getting them to understand Battle Master’s sci-fi feel was trying. The hardest part was that the older guys at Toshiba EMI in charge of the money simply didn’t understand the appeal of heroic characters like Ryu, Ken, Guile, and Chun-Li. They took special note of the fact that E. Honda was a sumo and Blanka was a kid who grew up in the wild, and came to us talking about how “these kinds of characters used to be in pro wrestling!” That led to them asking if we could make a fighting game consisting entirely of freaks and weirdos. Extremely troublesome. Our target was middle and high schoolers and adults who liked games, but these old guys had such a limited range of understanding. If we followed their directives we’d only end up with kusoge! I wanted to tell them off so badly, but I somehow managed to hold back.

Thankfully we had the support of System Vision’s president, there was a person by the name of Hakamada-san at Toshiba EMI who liked fighting games. Iimura-san put in the good word for me and told them to trust what I was doing, so we were able to avoid a worst-case scenario.

You did the animations for Syoh and Ranmaru all by yourself, right? Thinking back on it now, is there anything you’re particularly proud of?

That’s right. The pixel art I created myself was for Syoh, Ranmaru, and one other character.

Syoh and Ranmaru, as the male and female protagonists, were the main visual representation of the game for sales purposes. Besides me, the two other artists had almost no experience drawing pixel art. Considering the sheer amount of work involved, it wasn’t reasonable to task them with the job. I really wanted to put someone with more experience and better skills in charge, but nobody like that was on the team, so I handled the work myself out of necessity.

With two staff members’ worth of work to do, I created sketches for two characters, starting with Body and Jian. Ultimately, the work of creating the pixel art for Syoh and Ranmaru came around to me last. I also created the initial sketches for Wulvan, Chan Suchin, and Watts.

Mr. T, who had done pixel graphics on Power Athlete, was assigned work on the female character Altia, but the end result was a character completely lacking in sex appeal. When I was making the graphics for Ranmaru I did my best to make her as sexy as I could. (laughs) But when Mr. T looked at the pixel art I’d made, all he did was poke fun at me. Making the female characters sexy is really important to any game, and he still made fun of me! Once he was put in charge of Altia, his lack of experience – and excessive shame – came right out to the forefront. I guess he was too embarrassed to draw a really feminine character. The horrible thing is that people didn’t see Altia as a female character. I wanted there to be more female characters as a contrast to SF2, but the end result was so slight as to be meaningless. We couldn’t go back and edit the graphics with our small team, either… The world at large would say Mr. T was just being sensible, but I don’t need that kind of sensibility. In fact, I make it a point of utmost pride that I have so much fun making female characters. *laughs*

More recent sprite artwork of various Battle Master characters made with the freeware art tool “GraphicsGale,” as seen on Powerudon’s website.

Unlike Power Athlete, Battle Master was only released in Japan. Do you know why it didn’t get an overseas release?

There were talks about an overseas version after the game went gold, but it sounds like they decided the lack of characters who looked like famous people – Schwarzenegger for example – meant the game wouldn’t sell. Personally, as much as it bugged me to hear that, I thought it might be possible to put some characters like that in if we made it work with the game’s setting. That was as far as the talks went, though, so it was not to be. This is just a guess on my part, but unlike Kaneko, it seemed like Toshiba EMI’s game department didn’t have a particularly strong foothold in the overseas market.

The Megadrive version of Samurai Spirits has System Vision listed in the credits. Were you involved with porting the game, and if so, what was it like?

I was only involved at the beginning, where I helped convert Haohmaru’s sprites to the Mega Drive. But not being able to make original games – along with a healthy case of burnout – led to me and Kikuo leaving System Vision for a while.

Do you remember when development began on Ragnagard/Shin-Oh-Ken? Why was it developed for the Neo Geo?

I’d left System Vision and had been thinking about making a game myself while working a part time job for about a year. On a day off, the phone rang from the president of System Vision, who asked me if I had any ideas for a game. When I went to the company to talk about the details, he told me they would be making a Neo Geo fighting game, and I was floored. We had been turned down by SNK when we worked on Battle Master, but this time we’d be doing it through Saurus. It was a fighting game for the Neo Geo. That was all I needed to agree to join the project.

There isn’t a lot of information available on Saurus, the little-known publisher of Ragnagard. What kind of company was it? What was your connection to the company during development, and what kind of relationship did it have to SNK?

My understanding now and at the time was that they were an affiliate of SNK responsible for porting Neo Geo games to consumer hardware. I never spoke at length directly with anyone internally at the company, so I don’t really know much about them, either. They mostly gave us advice on how to design Shin-Oh-Ken as an arcade game. Very simple stuff, just talk about making the design of the game simpler. We corresponded back and forth with them, but while the release date for Shin-Oh-Ken was June 13, 1996, the game wasn’t actually released until about two or three months after that.

One of the points that came up when we signed the contract to make a Neo Geo game is that the release of SNK’s games took priority, and I heard that the ROM burning plants stopped manufacturing ROMs for third-party games. This was around the time when KOF96 went on sale on July 30, 1996, so Shin-Oh-Ken being pushed back was probably the result of us being in the same window. The ROMs for Shin-Oh-Ken simply didn’t exist on its release date.

Ragnagard’s stages and setting have a very different atmosphere than Battle Master’s. Was there anything that influenced you? How did you decide which gods and mythologies to include in the game?

The president of the company asked me to come back to plan a game. When I got there, he showed me a draft for a fighting game the Mr. T I mentioned earlier had made, a serious cyberpunk game with a roster full of military guys. Nothing about it hooked me. All of the characters looked like sidekick types, and when I asked the planner who came up with it for a reason why, he couldn’t give me a good answer. I didn’t want to hear the “correct” answer, I wanted to hear something that showed passion, something with impact that we’d actually want to work on. If he convinced me of that, I would have joined the project and given my full support.

But listening to him laugh while attempting to explain his ideas just pissed me off. “Is he TRYING to waste another golden opportunity?” I wondered. He told me he wasn’t giving it his all yet, or that he knew the ideas weren’t that great. All attempts to cover for himself. He hadn’t given anything any serious thought. He persistently asked us questions, but he didn’t seem to understand my intentions. Why couldn’t he just have some confidence and say he was willing to die with the plan he’d created? Sorry to Mr. T, who’d put everything together, but we ended up starting over from scratch with the ideas I’d come up with. The president of System Vision had called me back to the company, and that’s what he wanted.

At the time we started development, Vampire/Darkstalkers, Samurai Shodown 1, and KOF 94 had just come out. I loved all three of them, but Darkstalkers was easily #1. If Darkstalkers was a game with monsters and demons as a motif, what about a game full of angels and gods? Even if the old guys at the company didn’t understand the characters in SF2, they’d be able to understand gods from mythology.

On top of that, there was a strong Japanese vibe to the game, so they didn’t push back much and everything went smoothly compared to Battle Master. SNK even gave particular care when deciding on a subtitle for the game.

Going back in time a little bit: the people at Toshiba EMI actually came to us with recommendations for the subtitle for Battle Master. “Strongest on the Planet” or “Strongest on <insert word here>” (a lot of different words fit).

They were all incredibly serious about the whole thing, but from our perspective it just seemed like a series of bad jokes being dragged out endlessly to the point of embarrassment. It just didn’t make sense with the setting and characters, so we asked them to stop and ended up with the subtitle “Kyuukyoku no Senshi-tachi” (Ultimate Warriors) as a compromise.

Anyway, we made it through the early stages of planning for Shin-Oh-Ken without much trouble, the president was happy, and I felt relieved too.

The previous plan for the cyberpunk game had stalled out, so the president, senior programmers, and my coworkers all told me how impressed they were. I was thankful, and thought “all that planning and careful thought I put in is paying off.” But it wasn’t like I saw the correct answer for everything. Half of it was luck. Whether or not a game sells is luck, too, but the presentation for the project was small-scale enough that I could keep the same composition.

There were things I wanted to do and propose to take advantage of the golden opportunity that had presented itself, and it was for that reason that I was confident we’d be able to see the project through to the end. I treated development very seriously, doing everything I could to ensure that we maintained quality. If I just blurted out everything I wanted in the game, then the guys holding the purse strings would get scared off, so I’ve found the best way to proceed is to make concessions at the beginning, and pack some of what you want into your compromises. (Not that this is actually the correct way to make a hit game or anything. Shin-Oh-Ken never sold.) *laughs*

“Correct” is just a medal you get after making a hit. In any field revolving around sales, there’s no logical way to look at something and say “this was the correct way to go” prior to release. There’s just a way that’s closer to “correct” that you do your best to stay within. No matter how much money and talented creators you throw at a game, there’s still the possibility that it simply won’t sell.

The main influences on the art and setting of the game were Masamune Shirow’s “Orion” and Tenchi Muyo, particularly the latter’s mixture of Japanese and sci-fi tropes, which were a perfect fit. There’s nothing directly referencing either in the game, but my thought process was definitely sync’d up with them. The character of Aquarion (called “Arkorion” in the official English release -ed) was there in an attempt to get people to realize that “Orion” was the source inspiration, and I was hoping people would discover the original work and become a fan of Masamune Shirow in the process. Whatever the case, I clearly didn’t do a very good job paying proper homage. *laughs*

Why was the decision made to use prerendered CG characters instead of hand-drawn sprites? Was it more difficult to animate things in 3D?

This was an extremely difficult decision for someone who loved Capcom’s 2D spritework as much as I did. At the time, my mentor Hideki Suzuki was really into the prerendered graphics that you saw in Donkey Kong Country and all sorts of DOS games, and strongly recommended we use a similar style. I finally had the chance to draw 2D pixel art for an arcade game, and swore to myself that I wasn’t going to let this chance get away, but Suzuki pointed out that animation quality would be more important than on any project we’d previously worked on, which meant drawing a crazy number of key animation frames.

“It’s going to be pretty difficult to get those all drawn within the deadline, won’t it?”

That shut me up. I’d pretty much just grandstanded in everything I’d done up to that point, and had no idea how to create a proper work environment for the amount of animation we’d need to create. I finally thought I’d have the chance to show my pixel art to the world on the same stage as SF2, and then that happened. Most brutal decision of my life. That wouldn’t have happened knowing what I know now. I would have been able make a stand, and propose a number of methods for creating pixel art for the game.

Ragnagard’s air combo system is a huge part of the game. Was there a reason the ground game was paced to be pretty slow? Were you influenced at all by Capcom’s X-Men: Children of the Atom and Marvel Super Heroes?

Children of the Atom never really struck me as a having a lot of aerial combos. Watching recent tool-assisted videos makes me realize that it absolutely did, though.

I’d wanted to include air combos since working on Battle Master, and had some unfinished attempts lying around. This is all easier to explain by actually playing, but I made it so that you can do weak and medium normal attacks twice during your jump arc (ascending and descending). I was hoping it would end up providing more depth, but couldn’t flesh it out much more than that. It just wasn’t very easy to get a lot of damage off of air hits, and you fell really fast too.

For Shin-Oh-Ken, I developed specific rising and falling moves to launch opponents into the air on hit – what we’d call “starters” today. The attacker brings the opponent up to their current height to continue the combo. Marvel Super Heroes had you “launch” opponents. The side taking damage went into the air first, with the attacker following from behind. That’s a difference between Marvel and Shin-Oh-Ken.

As another aside, Shin-Oh-Ken’s location test took place at an arcade game corner inside a building called “Sugai,” and we got to hear feedback from the players. It was snowing outside and the streets were frozen, so it must have been sometime in the middle of December. They even went ahead and put the game in a Megalo cabinet with a huge 60-inch monitor! We had a few days planned for location test, and on the second day the owner swapped out the game in the other Megalo cabinet to Marvel Super Heroes – which was the first time I saw the game. So I put my work aside and sat down to play it. *laughs* There was also the D&D sequel Shadow Over Mystara in a new cabinet. After a few days, Marvel Super Heroes disappeared along with the other test games. I kept going to Sugai for a while to play Mystara while waiting for Marvel Super Heroes to show up for good, though. *laughs* I didn’t have a chance to play it normally until sometime after that. By the time I forgot about it, it showed up in a nearby game center.

Honestly, if Marvel had come out sooner, it probably would have affected the design of Shin-Oh-Ken. I was a devoted follower of Capcom during the fighting game era! Nishitani and Akiman were like heroes to me – no, gods.

One of the reasons the speed of ground combat is on the slow side is because people on the team wanted the CG characters to have fluid movement. I’d tell them the idles and walk cycles were fluid, and they’d fire back by telling me to make the attack animations full-frame too. I explained that if you did that the entire game would feel sluggish and slow, and that we had to make them faster, but it was bafflingly hard to get them to understand.

A lot of important elements were neglected just because the graphics were CG. For some reason, CG held this strange power that drove people crazy at the time. *laughs* With no other choice, I asked one of the programmers to loosen the cancel windows on normal moves and make it easier to do combos. In the end, as a result of how over-animated the characters were, a lot of people at the location test complained about how sluggish the game felt.

Not talking about speed here, but I consider the ground game to be fundamental to fighting games and wanted to make sure that the ground game in Shin-Oh-Ken was good. Plenty of fighting games had already come out by that point, but I saw it as one of the essential elements that SF2 had established.

What players often said – including myself, of course – was that they wanted to play a new game with a real sense of personality. If you take this request seriously and try to make a game that actually meets those demands, however, a tragedy occurs. People will complain that your game is too different from SF2, that SF2 did it better. That’s right. All we can do is compare to what we’ve seen before.

But I knew where they were coming from. When I heard that they were porting SF2 to the SNES, I couldn’t wait. Ranma 1/2 Chonai Gekitohen looked similar enough, and I bought it in an attempt to tide me over until SF2 came out. Then it turned out that you blocked with the L/R buttons and jumped by pressing a button. Not what I was looking for. I wanted to play a game where you blocked by holding away from the opponent and jumped by pressing up, dammit!

Ranma wasn’t a bad game, but because it looked like SF2, I unfairly criticized and resented the developers for some of the key decisions they made. Power Athlete, too, was criticized for not allowing you to crouch or create satisfying combos.

“It was too different from SF2.” “SF2 did it better.”

It may sound like these kind of players have developers wrapped around their finger, but when they say they want to play a “new game” what they mean isn’t that they want to play “something different” but that they want to play something like whatever it is they’re currently obsessed with. If they just wanted to play something different they’d play an RPG or shooting game or something.

Just changing the characters and setting makes the game fresh and “something new.” Players don’t want to play something that strays too far from SF2’s path. That’s just one of those facts of life. What I’ve described above is the foundation for fighting games. But I wanted to experience something new, too. I’m selfish like that. *laughs*

Beginning players of Shin-Oh-Ken will end up playing it a lot like SF2, which I expected since that’s what the core fundamentals of the game are based around. But fighting games make you want to dig deeper to see if something else is there. My goal was to include new elements that would support the core fighting game base, and ended up with a game that allowed you to duel in that place you previously only got to move around in for an instant – the sky. Players who understood how air combat worked had a clear advantage against players who had only played SF2. Learning just three new control elements – air dash attacks, and special high/lows – opens the way to a relentless aerial offense. They were also simple to execute just by reading the instruction card, and required none of the precise timing or reflexes demanded by parries or crouch techs in other games.

In the air, you can guard multiple hits, and perform a “guard dash” by holding back while dashing. These were all implemented to give players a chance to avoid damage in the air and get back to scrambling for hits again.

Basically: the ground in Shin-Oh-Ken is a traditional field used for combos, while the air is a place where you trade hits back and forth. The player in this video is probably using about 80% of the systems in the game.

How did you conceive of the English title “Ragnagard”?

They told me to think up a name for the overseas release, and I remember thinking that yeah, if you don’t know Japanese, “Shin-Oh-Ken” doesn’t really tell you much about about the game. Mr. T had helped out with some of the details for the game’s setting, and we worked together to brainstorm the name “Ragnagard”.

We matched some words from northern European mythology: “Ragnarok” -> “Destiny of the Gods” -> “Beyond the Battle of Susanooh”.

From there we started thinking of names with suffixes like “<something>gard” or “<something>heim”, trying to match the meaning of heaven and earth taken from Aquarion. The people in charge started getting impatient waiting for us to think of something, though, so we just went with what we had.

Shin-Oh-Ken was originally going to be named after Syoh’s dragon punch move in Battle Master – “Cho-Shin-Ken” – with the intent of hinting that even though the publisher had changed from Toshiba EMI to Saurus, the developer was the same. As for the name Shin-Oh-Ken: the “Shin” and “Ken” (“god” and “fist”) hinted at a battle between gods, while the “Oh” (“phoenix”) made you think of the sun’s light, or the right to rule, providing a motif that suggested the battle for transfer of power in Aquarion’s heaven. It’s a name that conveys meaning more through the separate parts than as a single word.

We also wanted to see about putting Syoh from Battle Master in the game as a guest character, ala Ryo Sakazaki in Fatal Fury Special. But we talked to Saurus and they said no. *laughs*

How was Ragnagard received upon its release in arcades? Were player impressions taken into account when developing the Saturn version?

For the arcade Neo Geo release, we didn’t receive any outside feedback from players. The voices we listened to the most for the Saturn port were those of my own friends and friends of coworkers. We added a combo counter like the one from Super Street Fighter II and Darkstalkers, and a display to show the level when guarding multiple hits.

The Saurus-developed Neo Geo game Stakes Winner 2 has System Vision’s name in it. Did you take part in its development?

I drew some of the characters. There were a lot of them, so somebody inside the company handled converting them to pixel art. After that, I drew the pixel art for a few backgrounds, and the hand holding the whip on the title screen.

I really hate the way the hair on the pixel version of the girl character ended up, and the way her nose looks is wrong, too… It’s nothing like the source art! But I never had time to fix it. So it goes.

System Vision vanished towards the end of the 1990s. Can you shed any light on what happened to the company?

I left System Vision shortly after we finished work on the Saturn version of Shin-Oh-Ken. I occasionally met up with an old coworker, but I wasn’t really that interested in the direction of the company after that, so I didn’t ask that many questions about their situation. It sounds like they were doing some small contract jobs. Besides games, I heard they did some site design and similar work. People started quitting the company until eventually there were only two or three members of the original game team left. The president made another company that had nothing to with games, so he probably shifted focus over there.

Were there any canceled or unreleased projects you worked on during your time at System Vision?

Nothing I was involved with. They weren’t making that many games to begin with. Another team was working on a stalled-out side-scrolling action game around the time we were porting Shin-Oh-Ken. If I remember correctly, it was a licensed game based on Bit the Cupid.

After leaving System Vision to go freelance, what kind of projects have you worked on? Can you talk about some of your work on indie projects?

I worked part-time at an arcade after leaving System Vision, and thought about maybe making a game by myself. (laughs)

After about three years of that, I was thinking about joining a company again and making games, and wondered about what my old employer was up to. That’s when I ended up joining h.a.n.d. After working there for about ten years I became design chief, and that’s where I am now.

As far as personal work goes, I bought Action Game Maker the day it came out and made a game with it. It didn’t take long before I bumped up against Action Game Maker’s limits, and realized I wouldn’t be able to do what I wanted with it, so about two years ago I started learning Unity. Haven’t made much progress though. I can use it at work, but I’m busy and barely have time to touch the thing.

I don’t know when it’ll happen, but I want to release my own game sometime.

Do you have anything you want to say to fighting game fans who are trying out Battle Master or Ragnagard for the first time?

They’re both over twenty years old, and not nearly so kind as modern games, so watch yourself. *laughs*

That was a great read. Would love to see more interviews on the japanese dev scene of the 90’s.

Great interview. Turns out I followed him on Twitter before reading this article for his pixel art, nice to learn who he was, and that he worked on that SFC fighter.

Great job, great interview. I loved the story of the creator of my favorite games.

I remember seeing SNES Power Moves in a magazine and being impressed. Soon after, I was surprised to know that I had a version for Mega (Sega Genesis) and it was exactly what I wanted. The Battle Master is a treasure to be polished. Ragnard surprised me with his modeled 3D style.