I’ve backed a fair few games on Kickstarter, and my general rule of thumb is “never back for more than you’re willing to lose if the project goes south.” That usually means I’m pledging something like $10-20 dollars. Some of these games have delivered, some have gone into the project mismanagement hell small-team games the find crowdfunding success often stumble into. If the latter happens, I’m not out enough money to make a fuss, and if the former happens, cool, I helped a game be a thing!

But if I could go back in time and edit any of my pledges, I’d give a whole lot more money to Hypnospace Outlaw.

Man, Hypnospace Outlaw. What a game this turned out to be! The end product wound up significantly different from the initial Kickstarter pitch: it changed from a weird action-game set in a 90s-style internet to an exploration/adventure game over the course of its creation. That was absolutely the right call, as the story (and, perhaps more importantly, all of the substories of the individual Hypnospace denizens) seen through exploring and interacting with the faux-online-service is a wonderful trip. I’m still working on finding all of the secrets of Hypnospace, and so many elements of the game continue to stick with me — I frequently find myself singing Chowder Man and Fre3zer songs to myself at strange times.

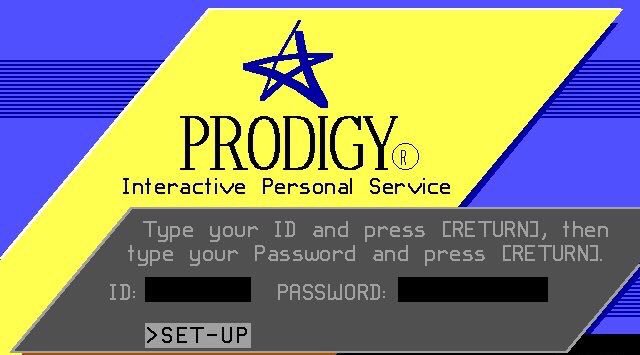

But one thing in particular about Hypnospace Outlaw really stirred a lot of emotions in me. I’ve been using various online services for a very long time, starting with the likes of Prodigy back in 1992 when I was but a preteen. I’ve seen many online communities spring up, thrive, and then fade away, a cycle that always seems eerily similar every time it happens.

When I played Hypnospace Outlaw, I saw all of the hallmarks of another online community destined for death. No, I’m not talking about the event that launches players into the game’s final leg: it’s very clear that the writing was on the wall for Hypnospace long before that happened. In fact, Hypnospace is doomed from the outset of the game, and you watch it collapse before your very eyes.

But while Hypnospace might have been fictional, the story it tells of a fractured, angry community and the corporate interests it’s at odds with are very real indeed.

WARNING: HEAVY SPOILERS FOR HYPNOSPACE OUTLAW PAST THIS POINT!

Prodigy was my first online community, and my first experience with online community loss. As a youngster with an interest in games and cartoons, I came to learn about all kinds of new and interesting things there (including some Japanese thing called “anime” that supposedly had some of the craziest animation you’d ever seen). I joined online clubs, posted about games I liked, wrote dumb fanfiction, all the stuff you expect a youngster to do online. I even got the Sonic 2 level select code from there way before any of the magazines of the time published it. (Also, according to Sega fans on the service, EGM was biased against the Genesis. Some things never change.)

The assorted forums were a primary reason most folks used Prodigy. They were great. That is, until Prodigy decided it wasn’t making enough money from monthly subscriptions and email charges, at which point they shifted over to per-hour billing. Given that you had to be online to compose and read forum posts, this was a killer.

Some folks I knew went to an up-and-coming thing called America Online, which let you read forums and mail offline. (I was one of them.) Some stuck on Prodigy. Some just vanished. The communities I knew that had formed around games and animation splintered and vanished, and bonds that had formed between people simply vanished into the ether.

Hypnospace reminds me of Prodigy’s walled garden in a lot of ways: its assorted “zones,” its colors and abstract visuals, its weird advertising tie-ins, but mainly in the way we see its users interact with each other. Early in the game, you see a campaign to get a new leader of the Goodtime Valley community elected across various member pages — the sort of popularity contest anyone who was jockeying for some status in an online remembers. There’s the notable online “celebrity” Chowder Man, a washed-up rocker trying to make a comeback via this up-and-coming Hypnospace thing, a bunch of kids arguing with each other over the bizarre musical movement Coolpunk, and a few notable corporate entities trying to endear themselves to users by piggybacking on these online trends.

But even in the early part of the game, the cracks in Hypnospace’s community are beginning to show. There are rumblings that a bunch of folks angry about the deletion of their communities who went and made their own unique Hypnospace area. Users selling services online want to use a payment processor called CapaCash, but MerchantSoft is banhammering anyone using it. People are complaining about harassment from various online agitators. There are rumors that using too much Hypnospace causes a medical condition called “beefbrain.” As a Hypnospace Enforcer, you look around, smack the people doing naughty things, and continue your browsing adventures, soaking up the odd personalities of Hypnospace’s populace.

Then the first test of the Outlaw game happens, a timeskip occurs, and you come back to a Hypnospace that’s fracturing right before your eyes.

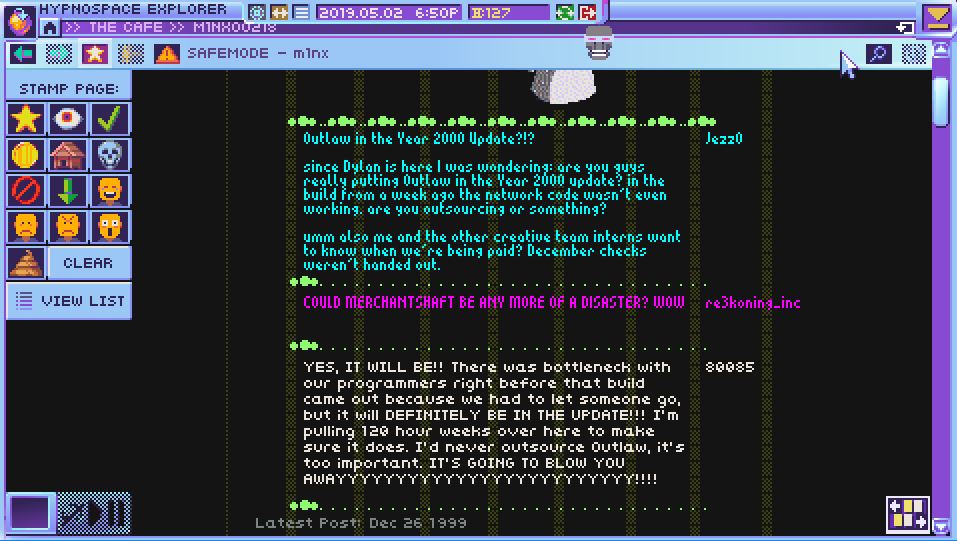

Goodtime Valley’s call for new leadership as turned into an all-out war: cartoon character Gumshoe Gooper is being targeted as copyright infringement by the Merchantsoft mods, and his supporters are not having it. Sandy, the lady everyone was previously supporting for leader, has been unceremoniously dumped by former friends for her opinion on the whole Gooper mess.

Coolpunk has imploded: a disastrous music festival where Chowder Man almost died and its biggest artist, Fre3zer, put on a terrible performace has caused most of the movement’s fans to turn away. Chowder Man’s bravado is gone, and Fre3zer’s desperately fishing for excuses. The Coolpunk section is decaying rapidly, as the main sponsor has left and most of the kids who glommed onto the trend have dumped it as uncool. A few hangers-on are begging people not to abandon the community that the music brought together.

As you revisit old pages looking for updates, you’ll notice a lot of the sites from before are either deleted or marked for deletion: either the user has left Hypnospace, or their free trial expired and they chose not to renew. Either way, it looks like people aren’t finding compelling reasons to stay in Hypnospace, which is extremely troubling from a corporate standpoint.

One thing that initially seems like a bright spot among all the chaos is the Freelands, the unique community assembled by a bunch of sci-fi, gaming, and fantasy geeks whose own zones were deleted. However, one look at the “manifesto” of the Freelands reveals that these people are among the most angry Hypnospace users, having had their favorite communities destroyed for reasons not made public. One of them is a Hypnospace developer who puts his community above his company loyalty, much to the displeasure of his superiors at Merchantsoft. Many of the Freelands users are threatening to leave the service for a competitor if their demands aren’t met.

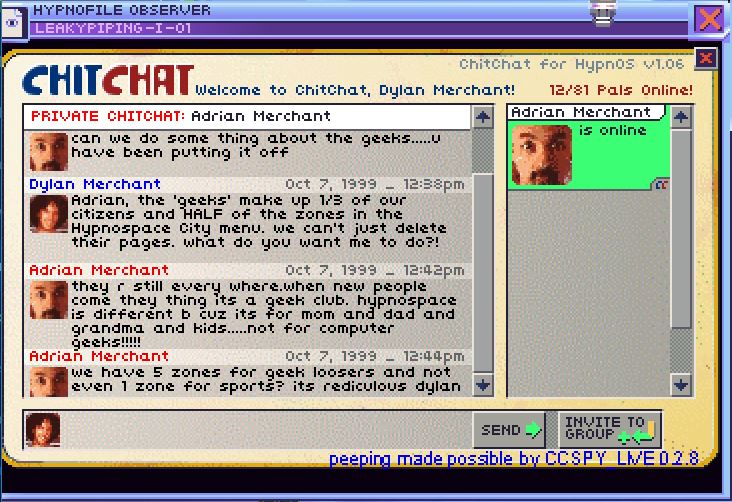

It’s around this time in the game that I first encountered a lot of the “underground” pages of Hypnospace: forums, secret sites, and mockery websites made by the hackers and agitators of the service. They have a lot of dirt on Merchantsoft, and what they’re discussing and revealing shows a company that’s willfully alienating its biggest userbase (at the whims of the founder) and pinning its hopes to be competitive in the new year on a big software update and Dylan’s new game that’ll blow the service’s main competitor out of the water. Of course, everyone is quite cynical about this, and they’re working to sew chaos by feeding those “beefbrain” rumors.

If this all sounds familiar, well, it should, because it’s a story that’s played out again and again across the Internet: a community forms, the corporate types in charge don’t understand what make it special, and they sabotage their own platform by destroying the threads that tie people together.

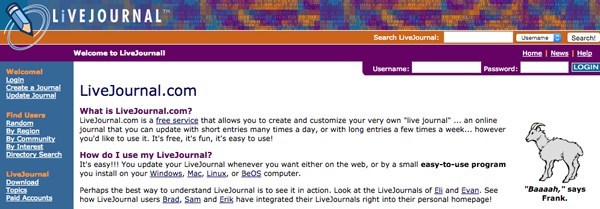

Let’s go back to reality now for an example. Like many folks in the aughts, I used LiveJournal a lot. I met many of my current online friends through the service, as it was a great way to find and follow people with similar interests and learn about them. Of course, it had its fair share of spectacular drama and cults of personality, but to this day I still think that it was one of the most enjoyable-to-use social networking platforms out there.

I used my LiveJournal frequently for a long time, but eventually, like most everyone who blogged on it during its 2000s heyday, I drifted away from it — mostly because my friends had all left for places like Twitter and Tumblr. A string of terrible moderation and content decisions, along with various problems with the interface and a sale of the service to a company with ties to the Russian government, had sent a lot of LiveJournal faithful packing.

I tried to use Tumblr for a bit, but I really disliked a lot of things about it. Though I attempted to come back to it a fair few times, it never really clicked with me. I’m sad about this, because my non-presence on Tumblr left me increasingly alienated from certain friends I’d grown close to on LJ — friends I still deeply miss talking to regularly. It’s not always easy for people to just move elsewhere when things go south on a platform, and that fact alone can ruin some of the best online relationships.

LiveJournal, of course, still exists, but it’s a mere husk of what it once was, and all of the various LJ clones that sprung up in its wake never became as big a thing. (Most of them died their own unceremonious deaths.) When a huge online community dies, it rarely shrivels up and vanishes — it often lingers, shuffling along like a zombie as its owners work desperately to squeeze what little money they still can from its shambling husk for years on end, refusing to acknowledge the role they played in its death.

When you reach the final stage of “live” Hypnospace, you see the zombie beginning to shuffle along.

The service’s Y2K update is live, but it’s noticeably extremely buggy and messy: the OS keeps hiccuping on you constantly, a lot of the new landing pages don’t work, and the whole thing feels like it was rushed out the door. Checking in on those underground areas reveals a lot of new details as to why this is happening: the programming staff is overworked trying to get the update in some sort of workable state while Dylan Merchant is obsessed with making Outlaw into Hypnospace’s “killer app.” There are hints that Merchantsoft might be in dire financial straits: the existing programmers are spread thin without new hires, and the interns are complaining about not seeing their paychecks.

The Hypnospace update itself is the sort of thing you expect from a clueless corporation, providing almost nothing the users of Hypnospace actually want. The sports section that the team killed all of the “geek” zones for is present, but — hilariously — not actually working. In an attempt to win back the alienated fandoms, Hypnospace is cynically making their own official Freelands-style area, but it’s too late — most of the Freelands crowd has left the service, leaving only broken and deleted sites behind.

Even more pages are deleted and gone. Sandy is leaving, finding no reason to stay after her former friends left her behind. Merchantsoft didn’t drive her away, but petty online group politics can be just as awful. Others, like the young girl who loves her SquisherZ, are being forced off. The guy who runs Hypnospace’s semi-hidden mockery site, The Dumpster, is giving up. The Chowder Man has recorded what is essentially his farewell song. As you look around, you discover more and more people dropping Hypnospace for various reasons. It’s clear that this is really hurting, and Merchantsoft is becoming increasingly desperate.

Merchantsoft fails to acknowledge its part in the destruction of its own community, leaving it scrambling to save Hypnospace by frantically backpedaling and pinning their hopes on a hit game. And that is how the chain of events that culminates in Hypnospace’s ultimate destruction happens.

Yet even among all of the sad, abandoned sites, you can find shreds of joy among the people trying to stick it out. Dig around a little bit and you’ll find something very special — a marriage proposal from resident metaphysical oddball Gus to the online spiritualist Sherri. Even as everything is crashing and burning around them, it warms your heart to see these two finding their joy together in a way that will outlive Hypnospace.

To me, it feels like no online community is forever. Be it small community forums that succumb to interpersonal politics, drama, and general human shittiness to big, corporate-owned platforms that prioritize investors and advertisers over users, online community spaces just don’t seem to be built to last. I’ve seen many a Hypnospace-like community crumble in the 27-odd years I’ve been online, and I can’t help but wonder: is it inevitable? Granted, most online communities don’t literally explode like Hypnospace did, but many have cataclysms of their own: recent events on places like NeoGAF and Tumblr are their own little Mindcrashes. Some people move on to the new place, some try to stick it out, others give up. It’s a similar story every time, and I think the dynamics of online interaction mean that every online community space will inevitably reach a point of unstoppable decay. Depressing, yes, but it’s a truth we must face.

Hypnospace Outlaw’s depiction of the dying-community phenomenon had a profound effect on me. Seeing the friends, family members, strangers, and online enemies of Hypnospace struggling against an uncaring machine that sees them as user numbers stirred up many a memory of my own online exploits and exoduses and made me think about the transient nature of our own online spaces. And, much like how folks are trying to reassemble the websites and communities of the Internet’s early days, the game ends with you trying to archive Hypnospace for both its previous users and those who have only heard of it secondhand, to try and give them some idea of what this vibrant platform was like. Even now, I’m still going through, trying to find the odd sites tucked away in the hidden nooks of Hypnospace. (I spent far too long looking for stuff I might have missed about Hypnospace’s impending doom in the process of writing this!)

In the end, our online communities may die, friendships may drift apart, and we may find ourselves on different paths, but the memories of our experiences there still remain. And that’s how Hypnospace Outlaw ends: Hypnospace may have collapsed in tragedy, but it’s clear that its existence was a special thing worthy of remembering, just like all the online communities that have come before.

One Comment