With the passing of Masaya Nakamura, founder of Nakamura Amusement Machine Manufacturing Company — better known to everyone as Namco — we’ve lost a man who was a pioneer of the game industry in many ways. When Nakamura bought out Atari Japan’s flagging division back in the 70s (offering far more money than rival Sega), he was spurred to add video game development to the company’s core business of kiddie rides, prize games, and other electromechanical amusements. From there, Namco went on to become one of the Japanese game industry’s arcade powerhouses during the game center boom of the 80s. Their competition with the other heavyweights in the arcade arena at the time — Sega, Taito, and Konami — spurred an incredible era of arcade innovation that helped advance game hardware and game genres to amazing new heights.

But here’s the problem: A lot of people don’t know much about that beyond Pac-Man.

While Namco had a US branch during the 80s, it was mostly a licensing arm until quite late in the decade.1. Games that looked like they’d have strong global appeal were quickly snatched up by the likes of Bally/Midway and Atari, while many others languished as Japanese exclusives, never to be seen outside of the country until MAME and the Namco Museums came about.

As a result, we have plenty of memorials dedicated to Nakamura speaking of him as “The Father of Pac-Man” (a title that really should go to creator Toru Iwatani), treating his legacy as if Pac-Man was the only thing that really mattered. Even without taking into account more modern Namco hits like Tekken, Ridge Racer, and the Tales series, this reductive titling ignores numerous games he helped spearhead into existence that had a tremendous impact on the industry. Sadly, because these games didn’t see much attention in the West, many players don’t know how important they really are. I’ve decided to highlight three very important Namco arcade games here to show just how important Nakamura’s legacy is — there are plenty more examples, but these three titles embody what Namco meant to a generation of Japanese arcadegoers and game creators alike.

Xevious

While Pac-Man was the biggest worldwide hit, its popularity in Japan paled next to Xevious. As one of the first games to put Masanobu Endo on the map, Xevious marked an incredible evolution in the shooting genre, which had lay stagnant for years with Space Invaders and Galaxian knockoffs.Here was a game that not only had a ship that could move freely about the screen, but had multiple ways of attacking: shooting the enemies that appeared in waves with the regular shot, or using a target to hit enemies on the scrolling surface below with bombs. It was a totally unique spin on shooting gameplay that was immediately copied and iterated on for years (with Taito’s Rayforce, released over 10 years later, being perhaps the pinnacle of its evolution).

The fact that you had to pay keen attention to the background below you drew consumers’ attention to just how good this game looked. Here we saw not generic solid-color backgrounds or starscapes, but beautifully detailed scrolling landscapes touched by the hand of Hiroshi “Mr. Dotman” Ano, Namco’s premier sprite artist. The ship and enemy designs were done by Shigeki Toyama, who I spoke of previously in this book review. You might not really think of games from 1982 as having much artistic direction, but the colors and designs in Xevious were so distinct and interesting compared to so much else that was out there at the time, and the fact that they changed as you progressed through the game was astonishing. The music and sound, too, was a big deal: as simple as the humming of the notes in the background during gameplay are, they established a tone for the game that, when combined with the sound effects, made it nigh-unforgettable, as Tetsuya Mizuguchi recounted in our interview with him.

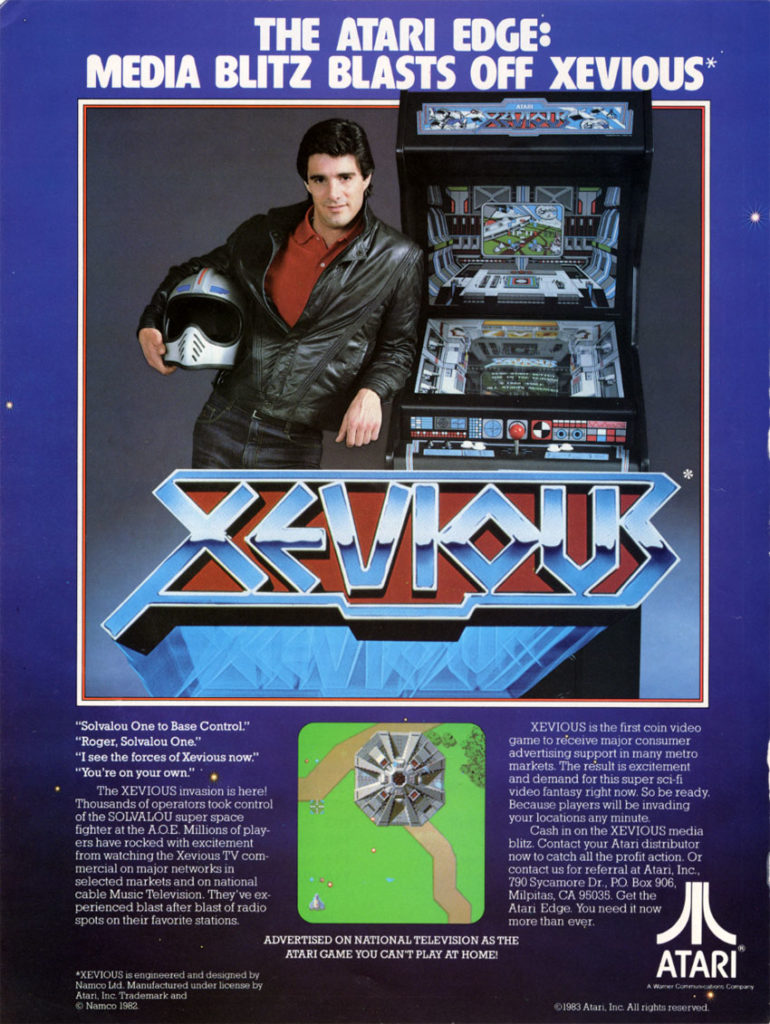

Xevious took Japanese arcades (and cafes, and everywhere else) by storm, and the numerous little secrets packed into the game became the stuff of afterschool rumormongering for a generation of Japanese kids. Atari of America smelled something good and picked up the rights to sell the game stateside, not wanting to miss out on another Pac-Man sized hit.

Unfortunately, the game didn’t fare as well in North America, though it wasn’t for lack of trying — as seen in the flyer above, Atari pushed the hell out of this game, with an advertising blitz designed to convince consumers and arcade operators that Xevious was a revolutionary game. While it’s hard to say why the game didn’t gain the same cultural cache here as it did in Japan, timing is probably a good guess: Atari didn’t release the game until 1983, at which point the market had begun to falter. While arcades didn’t suffer as hard of a crash as home consoles did, operators were operating with a lot more caution.

The Tower of Druaga

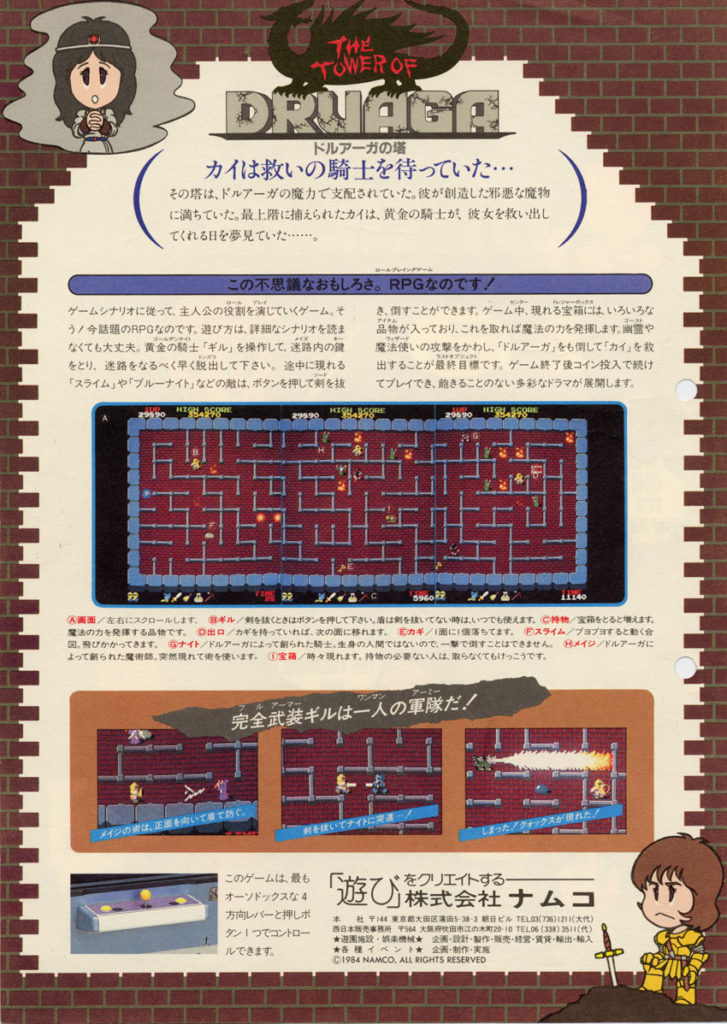

Out of all of the games I’m highlighting here, The Tower of Druaga is easily the one that’s aged the most poorly. In fact, if you go into this game cold, it feels downright unplayable by modern standards. That doesn’t make its impact on the game industry any less important, however.

Druaga, like Xevious, was designed by Masanobu Endou, who was becoming one of the industry’s first superstar designers.2 The Tower of Druaga could perhaps be described as a very early exploration-driven/puzzle-solving action/RPG, predating Zelda by a year. You control the legendary hero Gilgamesh, who has to rescue the maiden Ki being held by Druaga in the titular title structure by braving 60 floors of mazes and monsters.

Kevin Gifford’s old site Magweaseling translated several 2ch posts about the origins of Druaga, including one where Endou himself explains the core concepts behind the game:

In order to get this game released to the public, I wanted to follow these core concepts:

– Keep costs low by making it a ROM swap for Mappy boards that weren’t earning any longer

– Make it seem like a straightforward maze game on the surface

– Include RPG and adventure elements

– Give the game an ending to keep players from going for hours on one credit

RPG elements were a novel idea at the time, and were mostly the domain of PC games — remember, Dragon Quest didn’t hit until 1986 — so putting them in an arcade game was quite unexpected. Endings were also still somewhat uncommon, as most arcade games, even with a “win state”, would loop endlessly, allowing the really good players to hog the machines (Xevious experts got to the point of being able to marathon the game).

What makes the game so difficult to play by modern standards, though, is how those RPG elements were implemented. Clearing the game involves finding specific treasures on certain floors: some are power-ups for Gil that reduce that game’s difficulty, some affect enemies like ghosts, and others are just things you need to access the game’s final few floors and the ending. The problem is that the method for finding these treasures can be incredibly obtuse, and the game drops precisely zero hints about what you need to do. Even worse, there are some treasures that actively hurt you, rendering the effort needed to find them totally moot. Combine these confusing design elements with the fact that Gil moves super slowly and attacks by pulling out his sword and ramming into enemies, and you’ve got a game that is downright cruel for anyone coming in fresh in 2017.

For its time, however, Druaga was revolutionary. Here was an arcade game that required skills beyond just pattern memorization and reflexes, asking you to constantly think outside the box in order to solve puzzles and deal with the game’s punishing expectations. In order to beat Druaga, you needed to work together with other players not just to share strategies, but to figure out its bizarre logic. As Kevin writes:

…Druaga succeeded in 1984 because it forced arcade rats to work together, writing down their discoveries in public notebooks and pooling their wits (and 100-yen coins) together to get to the end. It created a community, in other words, just like Street Fighter eventually did — one that wrote strategy guides and dojinshi in droves. In a way, Druaga solidified the concept of a “game fandom” in Japan more than any other individual game.

Unfortunately, this sort of culture wasn’t particularly prevalent in the US, and Namco quite understandably skipped over releasing Druaga here.

In terms of its influence, it’s not hard to see how Druaga directly impacted some of the action-RPGs that came in the years following, specifically titles like Zelda and Ys. While the puzzle solutions in the original Zelda aren’t quite as bizarre as the means of getting some of Druaga’s treasures, you’re still required to think in novel ways to get past obstacles that would just be a brute-force exercise in other games of the time. And hey, don’t the Wizzrobes behave a lot like the vanishing, magic-shooting enemies of Druaga? Hmmm!

If you want more Tower of Druaga, Kevin Gifford’s Youtube channel has an annotated-in-English version of Game Area 51’s complete walkthrough, including how to get all the treasures and what they do. Friend of the site Ant Cooke has also written about it. If you want to play it… well, it’s in several Namco classic compilations, most notably Namco Museum III. Good luck, and I hope you have a lot of patience…

Valkyrie no Densetsu/Legend of Valkyrie

If Druaga was the game that helped establish the groundwork for future action/RPGs to come, Legend of Valkyrie was the game that took them to new levels.

In 1989, the RPG genre was well established. Though it was most popular on PCs and home consoles, arcade developers were experimenting with ways to implement RPG-like elements into arcade titles successfully, resulting in games like Sega/Westone’s Wonder Boy in Monster Land, Jaleco’s Legend of Makai, and Taito’s Cadash. Namco, having essentially pioneered RPG-like elements in arcade games with Druaga, also hopped on the trend with an arcade-only sequel to their original Famicom game, Adventure of Valkyrie. It was a massive hit.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0uNbL39pylQ

The Famicom game that Legend of Valkyrie is a sequel to is very much in the vein of the original Zelda: small character sprites, large map screens, lots of mazes and wandering around really confused — honestly, it’s not a particularly great game. Thankfully, Namco threw out almost everything from Adventure of Valkyrie when making Legend of Valkyrie save for the overhead perspective, making numerous changes to make the game palatable for an arcade-gaming environment. Gone were the dull tiled landscapes of Bouken, replaced with exquisitely detailed backgrounds and enemies that took full advantage of the powerful System II hardware’s scaling and color display capabilities. The plodding, clunky gameplay was revamped into a fast-paced, action-driven epic with exploration and platforming sprinkled in. This was the ideal sequel in every way: taking a game and making it into something bigger and better that only the arcade hardware of the time was capable of delivering.

Where Legend of Valkyrie triumphs is in its playability. The smooth, responsive controls make navigating the warrior-maiden through the beautiful yet perilous areas of Marvel Land a breeze. Combat is easy to grasp, with purchasable power-ups and magic spells earned through exploration adding extra depth to the overhead run-and-slash gameplay. Brief cuts of dialogue between areas and from random NPCs help you with hints on where to explore and elaborate on the overarching story. It’s all accompanied by one of Namco’s best soundtracks, filled with uptempo, melodic tunes that inspire you to fight ever onward.

Legend of Valkyrie’s influence on action-RPGs that would crop up in the next few years down the line is readily apparent. Visually, the game set a tone many other games were eager to imitate: an overhead view with bright, colorful, varied landscapes, a detailed central character with lots of actions and animations, and big enemy sprites and bosses for the player to overcome. The exploration here relied less on obtuse puzzle solutions and more on paying attention to your surroundings and listening to NPCs to get hints on where to go to acquire magic and treasure. Boss fights relied on a combination of skill and resource management, challenging the player to use their weapon power-ups and magic wisely to defeat some of the game’s toughest enemies.

It’s also worth noting how much of an impact the Valkyrie character herself made. She easily won the Gamest favorite character poll from 1989, and quite handily won a special survey of favorite female characters for the first of Gamest’s Gals Island special issues. In an era where a woman in a protagonistic role was still quite uncommon, Valkyrie was a breath of fresh air: cute yet elegant and refined, skilled in combat, and animated in a way that made her feel vibrant and full of personality. She remains of of Namco’s most visible classic characters to this day: even though Legend of Valkyrie skipped an international release, she still shows up in numerous Bandai-Namco published titles in both major roles (Project X Zone) or in cameos (the Tales series and Soul Calibur).

While there’s no official English arcade version of Legend of Valkyrie, there is a special English edition of the game available exclusively on Namco Museum Volume 5 for the PSOne. It’s also available on the PlayStation store, so if you want to experience this game but don’t have Japanese knowledge, that’s the best way to go. (Plus you can play it on your Vita, too!) I highly recommend it — few games age quite as gracefully as this title has.

There you have it: three amazing, incredibly influential Namco games that released under Nakamura’s watch, all of which are just as important to gaming history as Pac-Man. There are other highly influential Namco titles out there as well: Libble Rabble, Baraduke, Pac-Land, Pole Position, Final Lap, and so on, but these three stick out in my mind the most when I think of truly important Namco arcade games. So when we remember the legacy of Nakamura and Namco, let us not focus solely on the yellow pizza, but instead celebrate all of the numerous amazing experiences the company brought to arcades — games that defined genres and inspired many of today’s game creators to make modern masterpieces.

- One of my biggest frustrations in studying arcade history is how poorly-documented a lot of dealing between US and Japanese companies during the 80s and early 90s are. Details like when Namco US started to sell their own cabinets are scarce. And furthermore, how did companies like Taito USA decide which games to sell themselves and which to sell out to Romstar?! ARGH ↩

- He has reportedly claimed that he was the person who convinced Shigeru Miyamoto to put himself in front of the media more. ↩

About Wizzrobes and the Druaga wizards… it’s pretty funny when you think about just how many things are suspiciously seen in Zelda, what with the shielded knights you have to hit from behind or the side (with lizard knights thrown in as a higher tier), the ghosts, the unkillable obstacle fireballs, all of the tools, the anemone-like similarly-named Roper enemies… Even a powerful monster-humanoid warlock holding a servant of the goddess, one of them after which the game is named, which you get told by the story scrolling in after waiting on the title.

I mean, these are all generic fantasy… but come on.

Anyways, I want a new Valkyrie game. For her popularity, she had way less games than she should. I seriously think of all classic Namco that’s what has most potential for a revival.