First off, I apologize for this review taking so long – I haven’t been in the best of physical health this week, and that combined with the craziness of family obligations over the holiday weekend meant that I couldn’t update the site as I wanted to. I’d intended to have this up around last Monday or so, but those plans came crashing down fairly quickly. I don’t want to disappoint gaming.moe supporters with a lack of site content, but alas, sometimes real life foils even the best-laid plans. I’m working on a manner of contingency plan for the next time such a thing happens. Anyhow, on to the main piece!

A while back I wrote a piece for WIRED about the subsection of the Japanese doujinshi subculture that caters to gaming devotees. Part of the reason why doujin fascinates me so much is because of the sheer variety of stuff people create under the term, and the fact that there are other extremely passionate nerds self-publishing books about all manner of delightful gaming minutae makes me very happy indeed. I interviewed a publisher under the name Zekuu for the piece, as his circle, Game Area 51, does some of the most impressive and in-depth doujin publications on retrogames and important people involved with their creation. Thanks to his work, I’ve become more aware of the contributions of many creators to games and companies that have notable places in gaming history.

Such is the case with Zekuu’s books about Shigeki Toyama, who has a lengthy history at Namco. I was mostly unfamiliar with Toyama’s contributions to gaming, but the two volumes of doujin Zekuu published – two interview books and an artbook – have taught me a great deal about the man who designed Mappy, the iconic graphical imagery of Xevious, and several arcade cabinets and logos. He was also a robotics designer, helping create everything from small animatronics to massive amusement attractions (such as the gigantic Galaxian³ setup at the Osaka Expo in 1990). Later, he’d also be a key contributor to the design of Sony’s AIBO robot dog. After learning so much about everything Toyama had helped create, I found myself filled with a profound respect for his incredible talent. (And, to be honest, I felt a little bit embarassed that I hadn’t properly recognized it sooner.)

Out of the three books, I chose this one for review because it’s largely art-based – and since I’m writing for a primarily English-speaking audience, it doesn’t really do folks much good to recommend an interview book in Japanese. It’s 242 pages long, B&W, and contains a truly astounding amount of design material for some of the coolest, most ambitious stuff that Namco ever produced. Without further ado, let’s look over….

Shigeki Toyama Works: Artworks Volume (Toyama Shigeki Sakuhinshuu: Artworks Hen)

Shigeki Toyama Works: Artworks Volume (Toyama Shigeki Sakuhinshuu: Artworks Hen)

Cover image: A sampling of titles Toyama’s talent has touched

(click on any sample photo to enlarge!1)

Before Namco was well-known as a videogaming company, they were Nakamura Manufacturing Company, makers of more general mechanical amusements. As the 80s rolled around and computers were becoming the new hotness, the general populace began taking an interest in robotics. One such early application of robotics was something called “Micromouse,” where a robot navigates a physical maze (like a lab mouse would) using programming and sensors. Micromouse was fairly popular in Japan in the 1980s, and it actually continues to this day: competitions and design classes still happen at several major US universities and overseas.

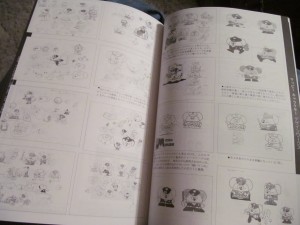

I bring this up because I actually didn’t know what Micromouse was until reading these books. It turns out that everyone’s favorite2 rodent policeman – along with his foes, the Nyamco cats – were originally robots designed for Micromouse by Toyama. Even before Mappy had his own game, he was delighting crowds by running mazes.

There’s a substantial portion of the book devoted to the design process of the original Mappy robot, as well as a smaller section detailing how the designs made the transition to early game sprites. Mappy won over audiences well before his arcade game even debuted, appearing at robot exhibitions in the early 80s – so much so that there are a couple of pages showing concepts for assorted Mappy-related toys and souvenirs (only a few of which were actually produced).

Another of Toyama’s robot creations was an animatronic robot band called PiCPAC. Similar in concept to the Rock-a-fire Explosion critters that graced Showbiz Pizzas across America (but infinitely more appealing-looking), they were a set of robots that played music for crowds at the 1985 Tsukuba Expo. The book goes into the development of the characters, the various names and logos being thrown around for the group, and all manner of promotional materials. I really liked learning more about this particular project, and I’m super keen on the robot designs – they’re cute and bubbly in that distinctly 80s anime way folks in my fandom age group feel a special affection for.

A few of you may already be familiar with PiCPAC, as they were polygonally recreated in Namco Musuem vol. 4 for the PSOne! You can listen to authentic recreations of their cute 80s J-poppy tunes, while a calvacade of familiar Namco pals watch. Now you know just what they’re all about.

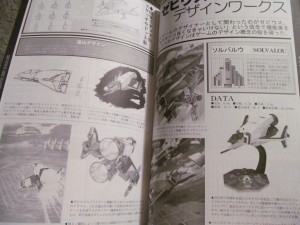

There’s a fair bit of argument as to what the first “shooter” game was, but the game that effectively caused the scrolling-shooter genre to explode in Japan was Namco’s Xevious. Toyama, with his mechanical design background, was asked to create the various ships and structures in the game as his first videogame project. The results are some of the most iconic images in classic Japanese arcade gaming. Many an old-school gamer in Japan has treasured memories of flying the Solvalou ship across the great green fields (and occasional Nazca line-imagery), shooting down the sharply contrasting waves of stark grey-and-white foes both in the sky and on the ground, eventually facing the oppressively huge Andor Genesis ship head-on.

As you might expect for such an important game, Xevious gets a hefty amount of attention in the book, with lots of concept and sprite illustrations to showcase how ideas evolved over the course of the game’s planning. It shows just how nicely Toyama’s elegant spherical and polyhedral mechanical designs translated into the fairly limited graphics of the time (though it’s certainly worth noting that Xevious was something of a graphical powerhouse of its day). Toyama would also work on mechanical imagery for the Famicom-exclusive3 Star Luster (an early first-person space shooter) and the arcade game Thunder Ceptor (a third-person into-the-screen shooter ala Space Harrier), both of which are also extensively detailed in the same way.

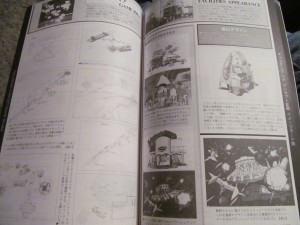

Even as Namco’s focus shifted away from robotics, they still needed Toyama’s expertise in designing various arcade setups. Final Lap and Winning Run were racing simulations with very elaborate cabinet designs. The book shows us just how many cabinet design concepts these titles went through (a lot), and gives a glimpse into the development of a vital part of the classic arcade experience that most people overlook: the machines themselves.

For the 1990 Expo in Osaka, Namco developed some elaborate themed attractions. One was a ride themed around the Tower of Druaga, while another was Galaxian³ Project Dragoon, an absolutely massive game experience. The original incarnation of Galaxian³ Project Dragoon herded a group of 28 players into a cylindrical theatre, where they were surrounded on all sides by game screens showing prerendered ship graphics streamed from a laserdisc player. (While laserdisc games had fallen out of vogue by 1990, it was the only means at the time by which to deliver detailed polygon CG graphics.) Players would take control of crosshairs and work with their fellow attraction-goers to take down the enemies. We’re shown many illustrations detailing not just development of the game itself, but also concepts for the attraction waiting halls, player seating, the facility structure, even the game’s logo. Though significantly scaled-down versions of the game were later released, it’s the huge attraction version that remains the most notable.

Toyama would continue to work with Namco on creating specialized arcade machines, which we’re given an in-depth look at. Phantomers was a ghost-hunting gun game with elaborate physical props and animated cutscenes for Namco’s now-shuttered Wonder Eggs amusement center. Alas, only the cutscenes seem to have survived. Prop Cycle, however, is probably more familiar: it’s a game that was a fixture of arcades in the mid-to-late-1990s, and Toyama was also heavily involved in its creation. There’s a staggering amount of material for the game, which had a surprising amount of attention paid to the development of its world. Apparently, a Prop Cycle 2 was also planned at some point as an RPG-style console game, but sadly cancelled.

This book, I feel, is something anyone with any interest in Japanese arcade game history (or just game history in general) should have in their personal library. I’ve learned so much about Toyama from Zekuu’s work, and I know I’ll be digging this one out as reference material (and to look at sweet 80s mechanical designs) in the future. Even the odds and ends, like the random sketches towards the end of the book, have an utterly endearing quality to them. Reading this fills me with a nostalgic longing for a life in 1980s/1990s Japanese arcades – a life that I never actually had, and can only experience vicariously through works such as this.

My only complaint is that I would have loved to have seen more development material from games that were popular in the West: Toyama also worked on stuff like Gunbullet/Point Blank, Panic Park, and Lucky & Wild, games that were fixtures of American arcades in the 1990s. That’s more an issue of my perspective as someone who grew up outside of Japan, however. I’m really awestruck by the amount of love and dedication Zekuu has put into chronicling the work of Shigeki Toyama, and these books serve as an inspiration in my own work as a games writer and interviewer.

So yes, as far as I’m concerned, this is a definite YES PLEASE BUY THIS. You might be wondering how well it works if your Japanese language skills aren’t the greatest – like I’ve said, this is the most image-heavy of the three Shigeki Toyama books. There is a lot of Japanese text, but the majority of information contained is purely visual. If you’re interested in picking the book up and you live outside of Japan, you have a few options: Mandarake will ship overseas, as will Amazon.co.jp. (If you’re buying from Amazon, I highly recommend the Utata Kiyoshi books as well for some gorgeous sprite and design art from Osman/Cannon Dancer, Little Samson, Cocoron and numerous other titles!)

Now somebody please tell that one extremely devoted Galaxian³ guy that he needs to get this for his collection, too.

- You might be wondering why I took photos rather than scanned the pages. Besides not wanting to wreck my book’s spine, the whole “scanning doujinshi” thing is a very touchy subject among JP creators. Since the whole point of this piece is to recommend you buy the book (and I’ve provided links to let you do so), it really makes more sense to take general teaser photos to just show you an idea of what you’ll get. If you want more detailed samples, click the link to Zekuu’s page beneath the book cover image. ↩

- well, except you, Lord BBH ↩

- Okay, yes, there was a VS System version of it, but you get what I mean. ↩

One Comment