Like many folks in the games media, I got a copy of Super Smash Bros. for Wii U a few weeks before it released to the public. Priority #1 was unlocking as much stuff as I could (A task that’s proven surprisingly tough – I’m still missing a few stages), particularly the extra stages and music. Among the unlockables is Pac-Land, which is an extremely cool stage with a lot of neat implementations of the progression and hazards found in the original arcade game.

Pac-Land, however, doesn’t include the original Pac-Land theme, probably because of rights reasons (it’s a chiptune version of the old Hanna-Barbera Pac-Man cartoon theme song). There’s no shortage of songs to pick from in the stage, though, and among them is a medley of music from something called Libble Rabble.

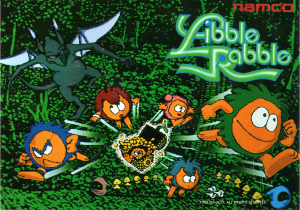

I’m pretty sure most folks outside of Japan are going to look at this and just say “Libble Rabble? What the HELL is that?” If you’re here, however, you more than likely took that next step of actually attempting to find out what the hell Libble Rabble is. Well, folks, I’m here to tell you all about it. Get your magic ropes ready, ’cause we’re going to take a good look at Namco’s beloved-among-devout-Japanese-retrogamers-but-utterly-unknown-in-the-West arcade cult classic.

Libble Rabble is the brainchild of creator Tohru Iwatani, the man who gave the world Pac-Man and propelled Namco into the forefront of Japanese arcade developers. While Namco produced numerous hits in Japan, many of these titles – now considered classics among Japanese retrogame fans – didn’t see the same sort of success elsewhere: Xevious, The Tower of Druaga… even Pac-Land didn’t really do much in the States, though it’s a historical landmark of the platform genre. 1 Libble Rabble, however, wasn’t a mega-hit even within Japan, despite the talent behind it. It’s got a cult following among the old-school arcade crowd there, however, which is a good part of what spurred my curiosity towards this title.

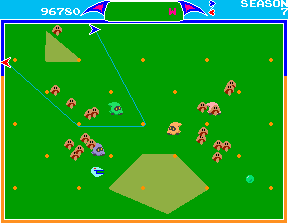

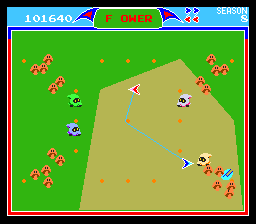

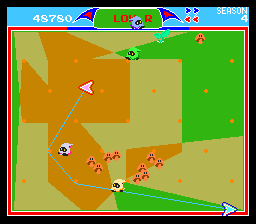

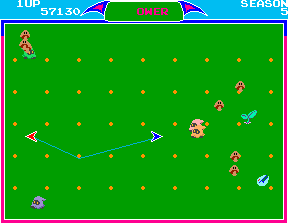

Libble Rabble puts you in control of two colored arrows, the titular Libble and Rabble. Between them runs a magical line of rope called the Bashishi. Every stage in the game – called a “season” – features numerous posts in varied formations that Libble and Rabble can string the Bashishi’s ropes along by moving about. By completely surrounding an area with the Bashishi, any creatures contained within are captured/defeated, items are collected, and hidden bonuses (or enemies) are revealed.

Much like Pac-Man, the game uses no buttons. But that’s where the control similarities end. Since you’re controlling two “characters” simultaneously, each one of them is assigned to a separate joystick for movement. It’s… weird.

Pictured above: a totally awesome custom Libble Rabble stick. Source

Pictured above: a totally awesome custom Libble Rabble stick. Source

“Pshaw!” you say. “I mastered dual-stick games like Robotron! I totally dominate with modern dual-stick controls! This oughta be no problem at all to adjust to!” Well… that’s what I said, too, but good lord can Libble Rabble be disorienting. It’s particularly bad when you mentally confuse which stick controls which unit. Yes, the game does try to help in this regard (Libble and Rabble look like arrows for a reason – to indicate which stick controls who), but the first time (and many consecutive times) Rabble will wind up somewhere to the left of Libble but still control the same way, it leaves you feeling utterly incapable of basic movement. I wouldn’t say it’s an inherently bad control scheme, just a highly unintuitive one that requires more effort than usual to get the hang of. (Which, as we’ll see, is something of a running theme with this game.)

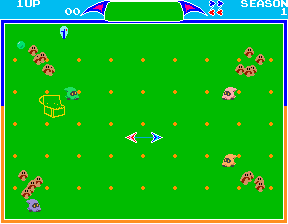

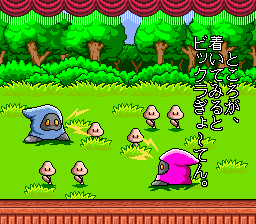

When you start a season, the stage is overrun with Mushlins, which look like tiny… well, it’s probably obvious. Your primary objective is to subdue these little buggers by surrounding them with the Bashishi. Capturing all the Mushlins takes you to the next season. It’s more complex than that, though – you’ve also got a time limit, signified by a colored energy bar that encircles the playfield. It’s constantly, slowly draining, and it doesn’t normally auto-replenish between levels. In order to refill it, you’ll need to harvest plants.

Plants exist in four phases, going from least to most energy restored: seeds, sprouts, flowers, and vegetables. (Or is it a fruit? hmm.) These cycle over time and remain in the same places even when the season changes. If a plant sf left alone long enough, it’ll move past its final stage and turn into multiple seeds, meaning that if you’re patient and careful with how you harvest, you can have more energy-replenishing items later when you might need them. Of course, you might also need them now, so deciding when and how to harvest is key.

Adding to the “to harvest or not to harvest?” conundrum is the existence of an invincibility state. If you can get your energy level over a certain point, you’ll be temporarily invulnerable to enemy threats until your energy depletes past the upper corners of the arena. Clearing the stage in this state also nets you a nice bonus. Since you don’t start with full energy, the only way to enter invincibility mode is by harvesting plants.

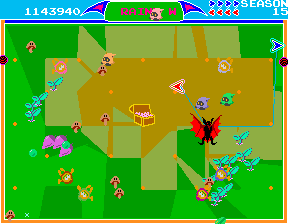

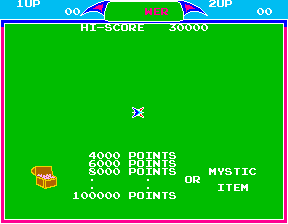

Being invincible, besides the obvious benefit of… well, being invincible, provides ample time for the side pursuit of treasure hunting. On each stage, there’s a hidden treasure chest containing a point bonus or special effect item. In order to reveal the chest, you must draw a small enclosure around the area where it’s hidden. If you enclose a large area and the treasure chest is somewhere in it, it will blink purple to tell you “the chest is in here somewhere, but you gotta go smaller, buddy!” Once a treasure is revealed, enclosing the area a second time will collect the item within the chest. Treasure hunting is key to getting higher scores in this game, and the game actually includes a short tutorial on finding treasures when you start. (It will also show the chests’ locations briefly in the first few levels.) Something else important also happens when you find a chest, but we’ll get to that in a bit.

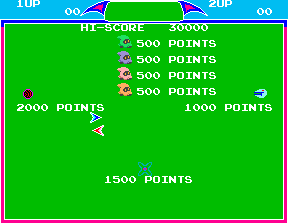

Of course, there wouldn’t be much of a game here if there weren’t some threats ready to ruin your day. The little Orko-lookin’ duders are Hoblins, and are your most immediate threat. They’re super cute, but if they touch Libble or Rabble, you’ll lose a life. When you initially start a season, or restart after losing a life, they’re the only enemies on the board that are a threat. Besides generally getting in the way, they can also steal energy-replenishing veggies. Trapping them in a Bashishi enclosure zaps them back up to their hutch for a little while, ala the ghost house in Pac-Man.

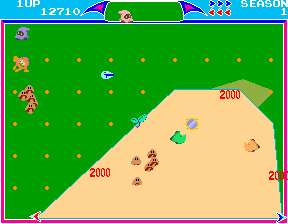

The blue-faced Not Pac-Man lookin’ fella is Shears, and true to his name, his purpose in life is to cut your Bashishi lines and ruin whatever good enclosure you might have going. He pops out from the sides and heads in a straight line, and is worth a nice 2K points if you can surround him. He won’t cause any damage if he touches Libble or Rabble, but he can and will screw you up at the worst times.

The dark, kinda fuzzy balls of malice are appropriately named “Killers.” These unpleasantries show up if you’re taking too long on a level, without so much as a “Hurry Up!” courtesy to warn you that they’re almost here to wreck your day. Unlike most arcade “TIME TO STOP HOGGING THE CABINET” enemies, you can actually surround and defeat these guys, though more will appear after a short while. It’s pretty dangerous to attempt to do so, as well – they kill on direct contact, but if they touch your Bashishi line, they will start draining your energy extremely quickly, even if you’re in invincibility mode (which can end said mode really, really quickly). Just finish the damn stage already.

The nucleus-looking Switchers are quite dangerous – should they touch your line, they’ll swap the positions of Libble and Rabble which, as I explained above, can be exceptionally disorienting. (You’ll need to touch another one to swap them back.) The scariest-looking of the bunch is the gargoyle. These guys don’t show up until you wake them by enclosing a certain part of the stage (usually a place close to the treasure chest’s location), and they’ll pursue Libble relentlessly once they’ve been roused, trashing plants along the way.

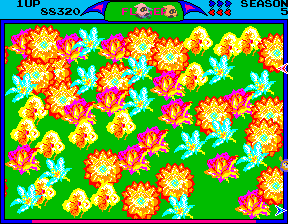

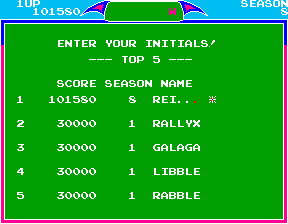

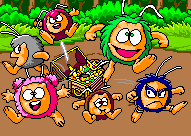

Finally, there are the Topcaps, the fuzzy faeries seen in all of the game’s promo art. Six Topcaps will appear and make a break for the edges of the screen when you uncover a chest. Much like the EXTEND letters in Bubble Bobble, each Topcap also corresponds to a letter, which appears in the top-center area of the screen if you capture one. Snag enough Topcaps to spell out a word and you can use your remaining energy to grab as much loot as you can in a treasure-filled bonus stage.

There are several potential words you can spell, and each phrase comes with an appropriate (and very graphically impressive for 1983) visual flourish when you spell it out. Pictured above is FLOWER, and other phrases include RAINBOW (imagery should be obvious), BRIDAL (bride and groom sprites appear, along with appropriate music), and whatever the current #1 high-score entry name is (a bunch of people sitting at arcade cocktail cabinets. Man, why did Japan move away from cocktail cabinets?). I’d love to get pictures of these, but frankly, I suck at getting consistent bonus stages. (You’ll see ’em in a movie link a ways down anyway.)

There are several potential words you can spell, and each phrase comes with an appropriate (and very graphically impressive for 1983) visual flourish when you spell it out. Pictured above is FLOWER, and other phrases include RAINBOW (imagery should be obvious), BRIDAL (bride and groom sprites appear, along with appropriate music), and whatever the current #1 high-score entry name is (a bunch of people sitting at arcade cocktail cabinets. Man, why did Japan move away from cocktail cabinets?). I’d love to get pictures of these, but frankly, I suck at getting consistent bonus stages. (You’ll see ’em in a movie link a ways down anyway.)

Thus does the game progress, moving from season to season with more Mushlins to control, more baddies to mess with you, and more treasures and Topcaps to uncover until you lose your final life. For such a graphically simple-looking game, there’s a lot going on at all times, and doing well in Libble Rabble requires both constant concentration and keeping tabs on numerous factors (time, enemies, the treasure, and so on).

What inspired this post, of course, was the musical medley from Super Smash Bros., and the soundtrack for this game remains beloved amongst early game music fans. Namco was one of the pioneers of memorable game music, and the bouncy, happy main theme to Libble Rabble by Nobuyuki Ohnogi lives up to this reputation. There are a few other jingles in the game as well, all of which are pleasant and eminently hummable. Besides hearing them all as part of the Smash medley, you can get the entire Libble Rabble soundtrack on iTunes! (You’re, uh, probably better off paying $3 for the whole shebang instead of buying 2-second jingles for a buck a pop.)

There are a few ports of Libble Rabble to Japanese PCs and consoles, including a Wii Virtual Console release of the arcade original. (Strangely, the game’s never shown up in one of the Namco Museum compilations.) The most noteworthy of these ports is definitely the Super Famicom version, which released almost eleven years after the original game. It’s a very faithful port with a few additions, most notably an illustrated intro sequence that tries to bestow some story to the game.

It does seem like the opening is where most of the cart’s scant 4 megabit ROM space went.

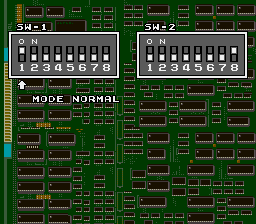

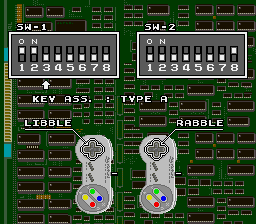

One of the most unusual aspects of this conversion is the option screen, which is set up like old arcade PCB dipswitches! The switch settings are similar to those of the original arcade game, allowing you to set things like difficulty, attract mode sounds, starting lives, etc. But there are other switches added: You can swap between “normal” and “arcade” mode (the difference between the two seems pretty subtle), set pause on and off, and change the control scheme.

So, about that control scheme – since the arcade game used a dual-joystick setup, Namco thought up a few ways to make it feel somewhat less awkward on the SFC. You can play the game with two controllers held vertically in each hand (with the + pad on either the top or bottom), two controllers held horizontally (with the right flipped upside down), or what’s probably the easiest way: using a packed-in controller attachment (shown with the game above) that slips over the ABXY buttons and acts as a second D-pad. Of course, emulation makes this considerably easier, as you can simply map a second analog stick to the buttons and call it a day.

So, about that control scheme – since the arcade game used a dual-joystick setup, Namco thought up a few ways to make it feel somewhat less awkward on the SFC. You can play the game with two controllers held vertically in each hand (with the + pad on either the top or bottom), two controllers held horizontally (with the right flipped upside down), or what’s probably the easiest way: using a packed-in controller attachment (shown with the game above) that slips over the ABXY buttons and acts as a second D-pad. Of course, emulation makes this considerably easier, as you can simply map a second analog stick to the buttons and call it a day.

Also unique to the SFC port is “Miracle Mode,” which is accessed on the title screen with the following code: Up x 5, Left x 4, Right x 3, Down x 2. Miracle Mode adds a few new bonus phrases and accompanying graphical flourishes. Since I positively suck at getting bonuses with any frequency, I’ll just point you to this Nico movie showing all the Miracle Mode bits. (The one for “POWERUP” is probably not what you expect, but it makes perfect sense.) It’s also got the full SFC version intro and all the original arcade bonus images, so have a watch if you’re curious.

So now that we’ve taken a lengthy look at the game, let’s answer the pressing question: why didn’t Libble Rabble gain the critical mass of Pac-Man? It didn’t even get picked up for international distribution at a time when the phrase “from the original creators of Pac-Man!” may have well been a license to print money.

When you actually sit down and play it, though, the reasons why mainstream success eluded Libble Rabble become pretty clear: the game doesn’t do a particularly good job of endearing itself to a new player. The control scheme is one factor, of course, but there’s a lot more to it. From the moment you start the game, there is a whole mess of stuff onscreen, a lot of it is moving, and there’s not an easy visual distinction between what will and won’t hurt you if you touch it. Compare that to Pac-Man, where the collectibles are all stationary and “anything that moves that isn’t Pac-Man” is clearly defined as a threat. The only enemy in Libble Rabble that conveys the “okay, this guy is obviously a hazard” feeling is the demonic-looking gargoyle.

Then you’ve got the complexity that winds up undermining a simple-looking game. For people like me (and probably most of the folks reading this), complexity’s certainly not a bad thing. However, the key to getting people hooked on arcade games is to start with a simple premise and easy-to-grasp controls and gameplay, gradually ramping up in terms of complicated stuff like scoring systems, bonuses, etc to make the player want to spend more time with the game. Instead, Libble Rabble is overwhelming from the get-go. Hell, the “training” mode consists of “here’s how to find treasures!” making it feel to a new player like that’s the sole focus of the game, when it should be teaching you about effective Mushlin corraling and managing your energy resources long before getting bonuses enters the equation. Basic survival needs to be mastered first, but the game doesn’t seem to get that.

As a result, your first few plays of Libble Rabble are exercises in confusion. There are these weird controls and so much stuff is onscreen and things are happening but what triggered them is a complete mystery (“Why am I invincible now? Why are these plants always changing? What’s with these weird electricity ball things?”). Compare this to Pac-Man, where almost everything is transparent and obvious and you can figure out the mechanics literally within seconds of your first play. While Libble Rabble has a fair bit more depth to it than other games of the era, you have to commit several tries to learning it before it all clicks, and even more to actually get good at it. It’s this obtuseness that makes it beloved by a specific group of hardcore players, but it prevented the game from ever getting serious traction in the mass market. 2 Add in additional factors, like requiring a non-standard control setup (making it harder to Western operators to convert cabinets) and a name that sounds quirky-cute-fun in Japanese but like childish nonsense in English, and it’s no wonder why Western distro never snapped this up.

But is Libble Rabble worth playing? It’s definitely worth looking at for anyone interested in arcade history, but whether or not it’s a game you want to practice and get really good at depends on what exactly you’re looking for from an arcade game. Since there’s no real ending (though it may very well have a kill screen – I couldn’t find any info about one), you’re strictly playing for score, and to do well there you’ll need to react to random elements with quick thinking and reflexes in order to to reap the big bonuses. It’s not the sort of classic arcade game you can switch on and kill time with for a bit – if you want to get anything out of Libble Rabble, it’s going to require effort on your part. But I think that if you’re willing to give that effort, you may just find Libble Rabble lovingly wrapping itself around your jaded gamer heart.

I’m still awful at it, alas.

- Considering how badly Midway and Atari had overexploited and botched numerous Pac-Man ports and spinoffs – and Namco’s own underwhelming Super Pac-Man – I wager that the Western public’s Pac-fatigue was in full swing by Pac-Land’s release. Japan didn’t get most of the Pac-junk we did, and that’s for the best. I don’t think that any Japanese fans cry themselves to sleep over never having played Professor Pac-Man on a real cabinet. ↩

- Then again, The Tower of Druaga is one of the most purposefully obtuse games ever created, and it was a hugely influential hit in Japanese arcades. Never reached the West, though, probably for that exact reason! ↩

Namco presented the game to North American distributor Midway Games for a possible release in the United States, however executives were lukewarm towards it and declined.