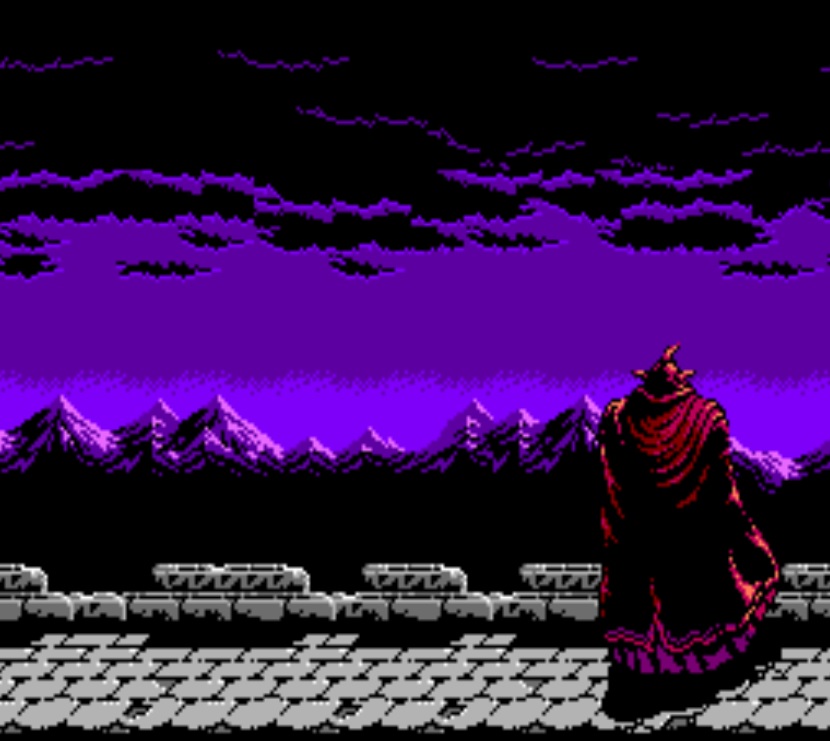

Few games are as fondly remembered by NES kids as the Ninja Gaiden Trilogy. It’s not an exaggeration to say that these games put the small publisher Tecmo on the map and set a high bar for many action games going forward. Of course, part of the reson why these games were so good was the talented staff behind their production, which included director Hideo Yoshizawa and composer Keiji Yamagishi. But their exemplary work in games continues far beyond the adventures of Ryu Hayabusa: Yoshizawa has helped in the creation of fan favorites like Klonoa and Mr. Driller, while Yamagishi is involved with game music production company Brave Wave.

I was given the opportunity to interview both Yoshizawa and Yamagishi at MAGfest 2018, and was eager to get some insight on the creation of these games. I was joined in this interview by the wonderful Jonathan Wheeler, alias ProtonJon, who is one of the biggest classic Ninja Gaiden fans I know. (His questions are notated by italics.) Read on to learn plenty of surprising details about the origins of some of the most beloved games of all time (and a few notable obscurities)! (I also suggest watching the official panel they had at MAGfest, too!)

Thank you very much for your time today. I wanted to start by asking you both how you wound up working at Tecmo.

HY: When I was originally job-hunting, I applied around various industries: mass communications, media, and whatnot, but I didn’t get any job offers from those companies. I ended up applying at a game company called Tehkan (soon to be renamed Tecmo – ed), and I was hired. I was originally enlisted to do sales of arcade boards to operators of game centers. I did that for around six months. But while I was doing that, I was offering a lot of ideas to the development department. After those six months, I was put into game development, where I wound up working on arcade games for about a year. Then I was put onto the home development division, where my first title as a director was Mighty Bomb Jack.

KY: During the end of my time at college, I applied for jobs at two companies: Sega and Tecmo. At my Tecmo interview, I wound up talking to the president at the time, Kakihara-san. When I showed him my resume, he asked me “oh, you’re in a band?” He wanted a musician to join the company and make music for games. That’s basically how I ended up joining. Kakihara told me I could work on whatever and however I wanted, too, so that degree of freedom was enticing.

Yoshizawa-san, you mentioned working on some arcade games. Can you tell us which ones you were involved in?

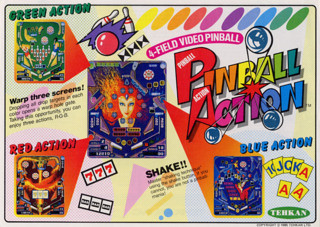

HY: My first arcade game was Pinball Action.

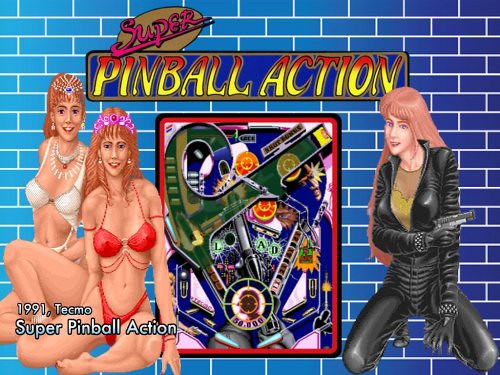

Wait, that wasn’t the one with the nude pictures, was it?

This one…

NOT this one!

HY: No, no, that was Super Pinball Action. The second game I worked on was Gemini Wing.

Okay, so I’m going to ask a super nerdy question here. There’s some speculation that a company called NMK did some work on the arcade Bomb Jack, do you know anything about that?

HY: No, they weren’t involved. They may have done later ports, but that was all in-house Tecmo.

The arcade version of Ninja Gaiden was a traditional beat-em-up, but the Famicom version was very different. Why the big change?

HY: I wouldn’t say that we really “changed” the Famicom version… rather, what happened was that both versions were in production simultaneously. They both had different directors. The president of Tecmo wanted an arcade game featuring ninjas, since he believed they were hugely popular overseas at the time. He wanted to take advantage of the “ninja boom,” so to speak. The person in charge of the arcade version was a fan of “belt-scroller” beat-em-ups, so that’s the sort of game he made. Meanwhile, the president of Tecmo had also asked me to make a Famicom game featuring ninjas. My personal image of ninjas were skilled warriors jumping up walls quickly and stealthily, which was a contrast to what the arcade division was doing. We wanted to capitalize on name recognition, so we decided to call them the same name. However, I was wondering, “These games are quite different, is this a good idea?” but the president insisted, so… that’s what happened.

It’s strange because in North America, the NES version was advertised referencing the arcade game, as if it was a port.

HY: Really! That’s the first time I’ve heard that.

It’s right on the box!

HY: Tecmo was the kind of company who would let creators do what they wanted, so… there weren’t many order coming from the top down. Maybe that has something to do with it? *laughs*

It’s interesting that the Tecmo president thought there was a “ninja boom” going on in America, since I heard something similar from Hisayoshi Ogura at Taito regarding the creation of The Ninja Warriors. Did you take any inspiration from other ninja games releasing around the same time, like Sega’s Shinobi and Taito’s Ninja Warriors?

HY: Hmmm, maybe my timeline is off, but didn’t we come out first? No? Hmmm… well, even if that was the case, we weren’t really thinking about other games. What we did reference during development, however, was American imagery of ninjas. We ended up special-ordering some foreign magazines to check them out, and we saw things like ninja using nunchaku, kung-fu, and magic… which aren’t seen in the traditional Japanese ninja. We’d call them something like “ninja-like” or “ninja-inspired.” *laughs* But not really authentic.

This explains why Ryu Hayabusa is a bad ninja. Most real ninjas don’t get beat up by birds.

HY: Well, those aren’t your typical birds! *laughs*

So I’m not sure if either of you two would know this, but — who thought up the continue screen for the arcade Ninja Gaiden, because that was absolutely traumatizing.

HY: I can assure you that wasn’t me! *laughs* That was directed by Ijima-san (who goes by “Strong Shima” in the game credits – ed), and I think it’s a reflection of his sensibilities… he also directed Wild Fang (aka Tecmo Knight), which is pretty similar. I think they actually had to censor that one a bit!

Moving on to the games themselves, how you both wind up working with Masato Kato?

HY: Kato-san was actually working as an animator for a while, but his pay was so abysmal that he had to look for a different line of work. (Some things never change. -ed) He could barely eat! He applied to Tecmo, and I did his interview. I decided to hire him, and he wound up joining my department. We had him as a visual supervisor, so he wound up doing the cutscene visuals for Ninja Gaiden II, and he wound up being a director for Ninja Gaiden III.

We had a lot of good discussions, and of course, we butted heads a few times.. but he was a very skilled artist, so I had him draw a lot of illustrations that would eventually influence the final cinema displays in-game. We made sure he was involved quite heavily with the story.

Disc art from the Brave Wave Ninja Gaiden series music release. This is one of Masato Kato’s drawings, as Yoshiawa-san noted after our interview.

How did the cinematics influence the musical direction of the game? At the time, cinematics like those in a console game were a rarity.

KY: Hmmm, I’m not really sure if there’s a fundamental difference for composing for a still shot versus a movie shot… but depending on what’s happening onscreen, you can implement the timing of sound effects into the music composition for movie shots.

HY: I did a lot of the planning documents that detailed the content and pacing of the scenes quite carefully, so I wound up putting a lot of such cues into the documents and pass it along to Yamagishi-san so he timed the music cues properly.

Since cinematics were rare at the time for videogames and the Famicom’s hardware was rather limited, did you feel they were challenging to make?

HY: I’ve always liked looking at storyboards, like the ones made by Hayao Miyazaki for his films. The NES is actually pretty good and showing still scenes,but when I was researching what the hardware was capable of, I discovered that there could be ways to implement cinematic displays scenes with a certain methodology. Nobody else was doing it at the time, so I ended up taking the initiative to try and make it happen. It ended up working out really well!

Actually, fun fact: half of the data on the ROMs is dedicated to the cinema scenes!

Were there any other games out at the time that had an influence on the direction of the cinema scenes?

HY: Not really. It was most just movies and animation. I really wanted to implement camerawork into the artistic design.

How involved were you in the overseas marketing and localization of the games?

HY: I had absolutely nothing to do with marketing. We relied entirely on Tecmo USA to handle that. The localization, though — I was actually the one who directed it. I hired a translator to create the English text, and I closely examined all of the text in that version. If I didn’t agree with a particular translation, I’d work with the translator until we had a script we could agree on.

The awesome jacket all the Ninja Gaiden II staff got

We you aware of the changes made to North American versions of the games, such as difficulty increases?

HY: I don’t think there are any differences…?

In Ninja Gaiden III, there are. The difficulty was a lot higher for the NA version, and passwords were removed… and double damage!

HY: Oh, NGIII… wow! Really? I had no idea! Maybe it’s Kato who did that. *laughs* The game came out in Japan first, and we made it easier because the other games were so difficult. But we got a lot of complaints that the game was too easy. Perhaps that’s why it was adjusted for the North American version, but I don’t really remember it well…

How involved were you with the ports of these games to other consoles such as the PC Engine and Super Famicom?

HY: I’d already left Tecmo by that point, so I had nothing to do with them, I’m afraid.

That’s probably for the best. The music in the SFC version… oof.

KY: I can assure you I had nothing to do with that! *laughs*

HY: I think the endings were cut, too? (The credits were removed – ed)

Did you have anything to do with the Ninja Ryukenden anime OVA?

HY: I directed that, actually!

Was it a different experience directing an anime, as compared to a videogame?

HY: Yes, it’s quite different! It was a pretty interesting experience, but I feel like the animation company handled most of the really difficult parts.

I’m surprised nobody ever picked it up to sell outside of Japan, given the game’s name recognition.

HY: Yes, quite a shame.

You’ve moved on to create new series for companies like Namco, but do you feel an attachment to the Ninja Gaiden characters? Do you wish you could do another story with Ryu and Irene?

HY: Well, yes! I consider the games I’ve made like my own children. But now it’s Tecmo’s property, so making a new NG game is something I can’t just decide on my own.

When did you both decide to move on from Tecmo, and what were your last projects there?

HY: It was a game we both worked on, a Super Famicom title called Radia Senki. I can’t say why I quit, exactly… *laughs*

It seems like Radia Senki might have been a troubled project. It was intended for a US release, but it never got one…

KY: That was a result of issues with the sales department. The actual game development was very smooth.

HY: Radia Senki game out shortly after the release of the SNES. By that time, interest in NES games from players and retailers alike had begun to wane significantly. Even in Japan, we only got orders for about 30,000 copies of the game. The US branch ended up rejecting the game’s release overseas.

So Yoshizawa-san went to Namco after that… Yamagishi-san, where did you wind up post-Tecmo?

KY: I stuck around at Tecmo for a little while longer, and worked on a few Super Famicom games there. I did music for Captain Tsubasa 3, Tecmo Super Bowl, and Tsuppari Oozumo. But a lot of people I’d respected at the company were leaving or had already left. The atmosphere was getting a bit lonely. I was engaged in supporting some of the younger creators at the company, but I began to feel like maybe it was time for me to move on, as well. Koei approached me around this time, and asked me to join their company. Of course, who would have known down the line that those two would merge… that’s not something I ever predicted would happen!

You composed a lot of music for the Tecmo Bowl games. American Football was never a huge deal in Japan, so how did you go about composing music for a game about a sport people there likely weren’t very familiar with?

KY: Actually, I’m a big football fan, so it wasn’t an impediment! When I was in college, I’d watch football games. Sometimes, the NFL would play exhibition games in Japan, called the “Coca-Cola Bowl” or the “Mirage Bowl.” I’d go to those games, too!

Are you aware of how popular Tecmo Bowl remains to this day?

KY: Yes, I am quite aware! *laughs*

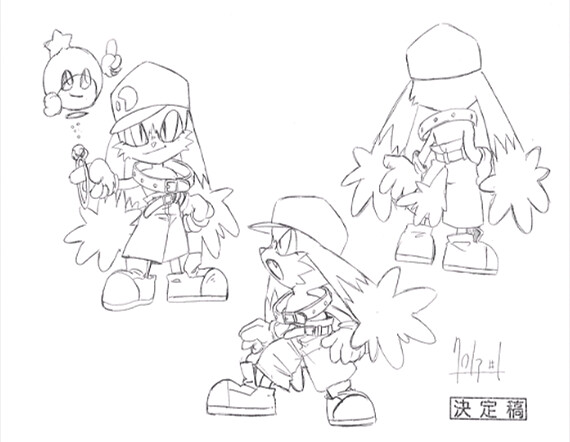

I wanted to ask Yoshizawa-san a question about the creation of Klonoa. At the time, the late 90s, so-called “mascot platformers” were beginning to fall out of fashion as a genre. What inspired you to create a game with a cute animal lead at a time like that?

HY: Klonoa actually began life as an adaptation of Shogakukan’s Spriggan manga. We were designing a 3D game based on that property, but unfortunately, the licensing fell through during development. However, we’d finished a considerable amount of the game, so we figured we should make an original title instead. While figuring out what kind of game to turn it into, we looked at the original PlayStation software lineup, and saw a lot of dark and serious games. If we made something like that, it wouldn’t garner much attention. We decided to go in the opposite direction and make something cute and colorful instead.

The idea of making the enemies inflate developed during this time. We had an internal character creation contest at Namco, and amongst all of the entries, it was Klonoa’s design that ended up winning out.

Sounds like what Sega did with Sonic.

HY: Sega invested a lot in Sonic’s creation, though. We just gathered a bunch of designs and went with the one that won out.

You mentioned that you weren’t trying to make a dark and serious game, but there are definitely some moments in Klonoa that rather distressing, particularly the twist ending.

HY: The ending of Klonoa was something I came up with myself. It’s a typical action/adventure game, where you advance through and see story scenes to get to the ending. I really wanted to have an ending that nobody was expecting.

Did you get a lot of feedback about it?

HY: We didn’t get complaints, but we did get a lot of fan mail about how much of an impression the ending left on people regarding the game. It built up quite a fanbase!

There was an attempt to resurrect Klonoa with a Wii remake of the original game. Do you think you’ll revisit Klonoa again anytime in the future?

HY: Personally, I’d like to make one, but I don’t know how Bandai-Namco feels about that. When Bandai and Namco merged, the vice-president from Bandai at the time was a huge Klonoa fan, and he basically spearheaded the remake. We originally wanted to make an all-new Wii Klonoa, but our supervisor from the Bandai side thought that would be too expensive. We ended up formulating a business plan: We’d “test the waters” with a remake of the first game, and if that did well, we’d port the second game, and then we’d move on to an all-new installment. If the remake sold well, we’d move ahead with development of the third game, and pump out the port in the meantime.

Unfortunately, the remake didn’t sell well, so it all got scrapped.

Yeah… the North American marketing for the game was really strange. It came with a coupon for a taco at a restaurant called Wahoo’s.

HY: Whaaa…? I never knew about that! *laughs* I think that would have been a good idea, if the chain was more widespread.

Yoshizawa-san, you also helped with the creation of Mr. Driller, another well-loved Namco series. Much like Klonoa, it came out at the time when non-competitive arcade puzzle games weren’t terribly popular. What inspired its creation?

HY: Mr. Driller was born from another designer at Namco who had wanted to make this kind of game. Fighting games were the most popular genre in arcades at the time, but we weren’t really concerned about conforming to that trend. This person — Nagaoka-san — was actually designing Mr. Driller for consoles originally. They ended up finishing the basic game, and when Nagaoka-san showed it to me, I thought that it was very interesting, but it might not do well in the crowded console market — so why not take it to arcades instead?

We ended up making the arcade version after that. It wound up being the opposite of the typical game development and sales pitch: You pitch to sales about the viability of your idea, and then you develop the game. In this case, the game was finished before it was pitched. We planned a location test in the arcade, and we truly had no idea how we were going to do — of course, we couldn’t actually say that to the sales department! In getting final approval, it was an involved process that went all the way up to Namco’s then-chairman. Eventually, Sales figured they’d sell about 3,000 PCBs, so we made them and they all sold out.

So to put it simply: We made a console game that we wound up putting out in arcades first because it was the most viable means of release.

Was the plan to connect Mr. Driller to other series such as Dig Dug present originally, or did that come about as more games were released?

HY: Actually, the prototype Nagaoka-san made wasn’t called Mr. Driller — it was called Dig Dug 3. The character was also the original Dig Dug character. So the game’s origins are, in fact, based in Dig Dug lore!

How did Kissy (from Baraduke) become Taizo Hori’s wife, and how did they divorce? *laughs*

HY: The part happened afterwards. One of the staff just thought the plot would be funny.

Namco has the UGSF now, which ties together a lot of different game universes. In some ways, it feels like Mr. Driller might have helped to spark the UGSF’s creation.

HY: There were a lot of people at Bandai-Namco who enjoy those sorts of supercollaborations, so I guess the idea just caught a lot of momentum.

Yamagishi-san, I wanted to ask you about your work at Koei. Can you tell us about the projects you worked on there?

KY: There’s waaaaaay too much to really talk in-depth about! *laughs* When I joined Koei, nobody internally at the company had ever composed game music before. There was no music team, and most of the music was outsourced.

Koei had made a lot of PC games, and there was existing music for these games, but they needed ports of these games to consoles to sustain their business. I was tasked with rearranging these tracks for consoles — but, as you know, that’s not something you can do with a simple port job. You have to make a lot of adjustments, figuring out how to take things like the melody and the bass and finding equivalents for its sound on different hardware. The SFC only has 8 sound channels, so some of the PC arrangements were a pain to get running on there! I had experience from my Tecmo days, though. One of the first games I worked on was Uncharted Waters 2, where I did the SFC arrangement. Those songs were originally composed by Yoko Kanno. You could say I “arranged” Yoko Kanno’s music for other platforms, but given how vastly different they sounded I’m not sure if that’s accurate… *laughs*

I worked on other titles as well, like Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Eventually, I was able to compose my own music for Koei titles after the company president took notice.

Yoshizawa-san, I wanted to ask about a weird little game you were involved in… a WiiWare game called Muscle March. How did that game happen? *laugh*

HY: Wow, I’m surprised you know about that game! Muscle March was created by a bunch of new Bandai-Namco employees at the time. They had one month to make a game for arcades as a learning experience. The idea was to make a game where you moved the joysticks for the character to do poses. They finished the game, but there was another arcade game at the time that was very similar. Before the location test began, the game was put on hiatus. When the Wii was released, however, I remembered that there was this nearly-finished game idea we still had sitting around. Given that the Wii used motion controls, I thought we should put it out on Wii instead. So I took it to Nintendo, they liked the idea, and things went on from there.

Interestingly enough, Bandai-Namco America created some really wild ads for the game. It got a lot of buzz because of that.

To wrap this up, I’m wondering if you have interesting anecdotes about game development you’d like to share.

HY: I actually post a lot of this sort of thing on my Twitter account. Please check it out!

KY: I can’t really think of anything interesting right now, unfortunately… *laughs*

If you want to see the sprites that were censored in Wild Fang, I recommend checking out the TCRF page. I uploaded one of the images there.

Thanks for the tip!