I once again attended MAGfest this year, and had a wonderful time presenting panels alongside LordBBH. (Check out the videos of our panels!) My good friends from Brave Wave Productions were also in attendance, and this year they brought Takashi Tateishi as a guest. Tateishi-san has had quite an interesting career: working on one of the most beloved soundtracks ever in Megaman 2, lending his composition skills to cult favorites at Takeru, and doing a whole mess of sound work at Konami in the late 90s. I’m extremely happy to have had the chance to sit down and chat with him about his career. Read on for some interesting anecdotes about early game music development… and also learn about the rarest official Megaman music release of all time.

konami

Konami versus the fans of Tokimeki Memorial: A Legal History

Hey, did you hear about the PUBG vs Fortnite legal case getting withdrawn? Boy, that thing was a complete disaster, huh? But ours is an industry filled with legal shenanigans… many of which, like Capcom v. Data East, Silicon Knights v. Epic, and now this, have ended disastrously for the plaintiffs.

However, it’s not always like this. We only really see these cases from a Western perspective — and, indeed, many of the most important legal cases in gaming, like the infamous Tetris debacle, were decided in US court. But there have also been plenty of legal issues surrounding games in Japan — see the recent spate of game bar closures — and one Japanese company is quite notorious for its use of litigation.

Long before #FucKonami was a trending hashtag, long before Western music game fans and developers cowered in fear of Konami’s legal threats, there were incidents in Japan involving one of Konami’s most popular (at the time) game franchises. These incidents earned Konami a great deal of notoriety among game fans in Japan as a litigation-happy tiger of a company that would happily devour its own fanbase. Somehow, though, these stories never drifted overseas, likely because the game involved was seen by the west as “some weird Japanese dating sim thing” that was of little interest or importance.

It’s time to change that. It’s time to take a look at Konami’s legal actions against one of its most fervent fanbases. Let’s examine Konami’s legal battle against Tokimeki Memorial fandom.

Before we start, perhaps it’s best to talk a bit about what Tokimeki Memorial (frequently abbreviated as Tokimemo) was, and why it was such a big deal.

Tokimemo is considered to be one of the defining “Gal-ge,” or games centered around fostering and nuturing a relationship with one of several eligible virtual women. In this game, you play as a high school boy going through the school year, meeting various girls and finding one you eventually want to win over. By paying attention to the girl’s likes and what she wants in a partner, you budget your time and raise stats to become more appealing. You also have to make sure not to annoy any of the other girls, because they’re catty bitches who will spread damaging rumors about you. Eventually, you’ll reach the end of the school year, where one of the girls — hopefully, the one you were aiming for — confesses her love for you under the tree of legend.

(If you want a slightly more in-depth and fun look at the gameplay, I’d highly recommend the Game Center CX episode centered around the game.)

Tokimeki Memorial did well when it debuted on the PC Engine CD in 1994, but it was the eventual enhanced ports to PlayStation and Saturn that really made the game blow up in popularity. Shiori Fujisaki, the pink-haired girl-next-door archetype on the PS and Saturn covers, became an instantly recognizable face across all of gaming. Konami had a huge hit on their hands, and merchandised the everloving hell out of it: to this day, you can wander into any Japanese secondhand stuff store and likely find various Tokimemo knickknacks.

Of course, with a hit game comes sequels and spinoffs, and they were numerous. The first sequel, Tokimeki Memorial 2, was a huge game spread across five CDs, and is widely considered the best in the franchise in terms of gameplay and presentation… yet it didn’t stick around in gamers’ hearts like the first game did. A disastrous move to 3D visuals on PS3 with Tokimemo 3 upset many, and Konami opted to focus instead on the growing otome market with Tokimeki Memorial Girls’ Side, which had you playing as a girl trying to impress a bevy of hot dudes. The last Tokimeki Memorial game, Tokimeki Memorial 4, released on PSP in 2009, and its very existence seemed like a surprise to many.

(A fun fact shared to me by my late friend Andrew Fitch — who formerly worked at Konami’s US branch — was that the weird PSP game Brooktown High was meant as a testbed to see if an “American Tokimemo” would work. We miss you, Andrew.)

Since then, Konami hasn’t done much with the series, aside from putting out the occasional bit of Girls’ Side content. Love Plus on the 3DS was seen by many as an evolution of the game’s concepts, though Konami basically destroyed that series as well. Currently, there’s a game called “Tokimeki Idol” on smartphones that looks like a really bad attempt to cash in on the Idolm@ster/Love Live! wave by using scraps of an old IP. The decline of Tokimemo itself is worthy of its own article, as it’s due to a variety of factors, but one thing that may have played a part was Konami’s antagonism of its own fanbase through legal means. Such as… Continue reading

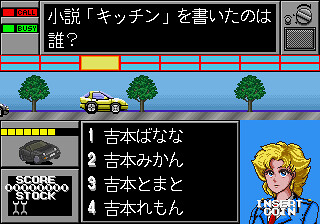

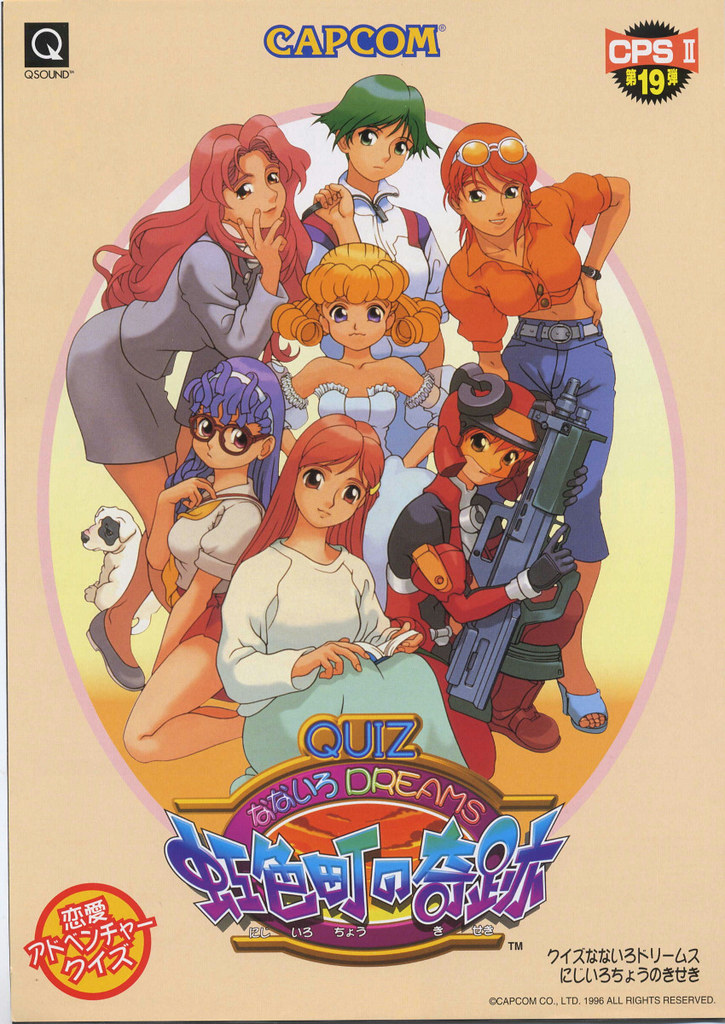

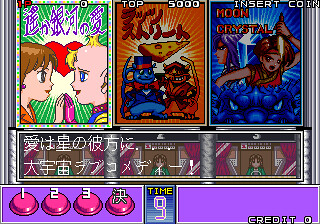

The Amazing, Unrecognized World of Japanese Arcade Quiz Games

Quiz games. They’re one of the most basic forms of game out there, going a long, long way back to the days of game shows on radio and television, persisting to this very day. They’ve also been a part of videogaming from the early days: as soon as ROM chips could feasibly hold a decent amount of text, quiz games started to appear in arcades and on consoles.

Nowadays, when you think of arcade quiz games, you probably think of something like the multiplayer setups you see at trivia nights in a local bar. This is the direction Western quiz games evolved in: they never really eschewed a game-show/board-game style format, and evolved to implement either real-money gambling mechanics or large-scale multiplayer, competitive functionality.

In Japan, however, things played out very differently. Arcade quiz games started to appear there in the mid-late 80s, through companies like Sega and Nichibutsu. As the 90s came along, a renaissance of quiz-game development created a unique, fascinating genre with an abundance of different thematic elements.

The genre first saw significant advancement through games like Adventure Quiz: Capcom World, a trivia game loaded with 80s Capcom fanservice, and Mitchell’s Quiz Sangokushi, which melded the question-and-answer format with strategic, territory-conquering gameplay. These games utilized elements of visual novels and strategy games to make the quiz experience more appealing and engaging. Other games put quiz elements into fun new genres: Taito’s Quiz Chikyuu Boueigun (“Quiz Earth Defense Force,” no relation to the current Earth Defense Force games by D3 Publisher) has you saving the planet in a story that’s chock-full of classic sci-fi parodies, while SNK’s Quiz Daisousasen (“Quiz Big Criminal Investigation”) is a detective story that morphs into a weird sci-fi/horror thing at the end. You still had game-show style quiz games too, but they were quickly losing ground to more ambitious efforts.

In some cases, publishers adapted existing properties but added a quiz-game twist, hoping the familiar name would draw in customers. This is how we got games like Saurus’s Quiz King of Fighters and Taito’s Quiz HQ, which combined existing game properties with a quiz-game element. As time passed, however, more and more experimentation happened. The mid-late 90s were really a golden age for arcade quiz games, resulting in a stunning variety of thematic and gameplay genres mixing in with traditional quiz elements.

Interestingly, quiz games tend to be very lengthy, sometimes taking an hour or more to complete from start to finish… which, in theory, goes against the short, focused play experiences arcades want to offer. You want to get people off that machine as quickly as possible, right? However, with these new thematic ideas, players became more committed to seeing the games through to the end. It doesn’t hurt as much to abandon a gameshow you feel like you’re not doing well in, but when you’re in the middle of a story about saving the universe? Hell yes you’re going to brute-force your way through with yen! Add a second player into the mix and watch earnings double!

Unfortunately, most the appeal of these games is lost on the West. Japanese quiz games might be the most culturally impenetrable games out there: not only do you have to be fluent in the language, you also have to be fluent in a variety of cultural elements. Sure, you might know the multiple readings of thousands and thousands of kanji, but unless you lived in Japan during the early 1990s and remember which popular talent of the time appeared in a specific ad campaign, you’re probably not going to get very far. That is, unless you cheat. Thankfully, emulating most of these games allows you to cheat through the quiz portions, making the games somewhat more accessible… though it does result in the game losing a big part of its inherent charm. (Plus, even if you do cheat, if you don’t speak the language you can find yourself making very poor choices.)

You don’t hear a lot about quiz games nowadays — the genre saw a sharp decline in development and interest after the 1990s. Currently, the big name (and basically the only name) in Japanese quiz games is Konami’s Harry Potter-inspired Quiz Magic Academy, which has a new arcade version releasing soon (along with a mobile version that is no doubt raking in plenty of money). Right now, it’s practically the only arcade quiz game in town, unless your local game center has an older game installed in a cabinet somewhere.

But where does someone who doesn’t know anything about Japanese arcade quiz games go to get a good sampling of what the genre has to offer? Well, that’s why I’ve taken the time to write this. Today, we’re going to take a look at some noteworthy Japanese-style arcade quiz games: One that, against all odds, got a localized release, and three others that showcase some very interesting experiences. Continue reading

Game Music Highlight: Salamander 2

I’ll be real here: I’m not a huge fan of most of Konami’s shooters, mainly because most of the stuff from the Gradius school of design punishes you harshly for any matter of mistake. I do, however, really like the Salamander/Life Force series, mainly because it doesn’t have those checkpoints placed strategically in the areas most impossible to clear when you’re powered down to nothing. (I also dig Gradius V for the same reasons.) Oh, and also because the soundtracks in them are amazing.

Gradius’s release in 1985 came at a time when sound hardware was beginning to evolve to a point where musicians could make songs that were far more musically complex than the 10-second loops ripped off of some public domain ditty. Konami was one of the leaders of this zeitgeist in the arcades alongside Namco, Sega, and Taito, and Gradius was among the first games that made people sit up and take notice of what game music could sound like. Hell, it was impressive from the point where you booted it up and waited for that bubble memory to heat up.

The musical legacy continued throughout the series and into its spin-offs, which brings us to Salamander 2, released in 1996. This was just a couple of years before Konami would begin releasing games like Beatmania and Dance Dance Revolution, and future Bemani maestro Naoki Maeda (along with arranger You Takamine) was already beginning to hone his craft in the game’s many uptempo, synth-heavy tunes. In fact, there’s one tune from Salamander 2 that I’m sure the VJ crowd knows very well, and it’s this one!

This song, “Sensation,” was remixed and later appeared in Keyboardmania 3rd Mix (and the PS2 home port, Keyboardmania II, which contains music from the arcade 2nd and 3rd Mix). This was not done by Maeda, but rather Shinji Hosoe, who has had a long and fruitful career in game music (and is one of the key figures behind game music label SuperSweep).

I’ll be honest: I don’t really like this particular remix. I know, I know, it’s sacrilege to say you don’t like a Shinji Hosoe song… or a piece of Bemani music. But something about it just feels off. Maybe it’s the different instrument samples sounding kinda weird, or maybe because it hits so many of my arranged game music pet peeves (“let’s cut out the backing instruments here, it’ll sound great!”).

But you know what? Sensation isn’t even my favorite Salamander 2 song. It’s this one, from later in the game:

It’s got that same fast tempo and heavy synth, but a very different mood to it: it feels more trepidatious, because now you’re further along in the game and shit has gotten real. If Sensation is all about “HELL YEAH LET’S KICK SOME MID-90S PRERENDERED CG ENEMY ASS,” Speed is like “Well crap, we’re really in this one for the long haul, aren’t we? Hope you’re ready.” There’s also a something kind of big and sweeping about it, especially when you hit that bridge of music before the track loops. Pretty great, if you ask me.

Naoki Maeda, like a lot of key Konami talent, is off doing other things these days: last I heard, he was at Capcom working on an arcade game called Crossbeats Rev. (I don’t remember even seeing this one on my last Japan trip, which leaves me a bit worried as to how it’s faring in the market.) Given that Konami’s keen to piss their valuable IPs away, it’s doubtful we’ll ever get any new music in this style… unless, of course, they make a Salamander pachislot. At least the sound could be nice, right?

The 2015 Gaming.moe Waifu Awards

Ah, yes, it’s that time again – 2015 has shuffled off into the history books, and the majority of 2016 lies untold before us! Which means it’s also time for a now-annual Gaming.moe tradition – the Gaming.moe Waifu Awards.

In case you’re wondering – no, we’re not awarding awards to our favorite game waifus, because I’d have the same winner every year. It’s a name we adopted in the general spirit of the site for non-traditional year-end awards. Rather than doing typical categories like “Best Graphics,” “Best Fighting Game,” and the ever-argued-over GOTY, we give awards based on weird, arbitrary categories based on noteworthy happenings of the previous year. (You might want to check last year’s awards to get a better idea, as I explain the concept a little more in-depth there.)

2015 was a very good year for gaming as a whole. We got lots of fantastic new releases, juicy industry drama, and promising new projects. Of course, not all noteworthy happenings were the stuff of major hashtags and gaming news site headlines. Let’s celebrate the best (and worst) Waifus of 2015! Continue reading

Awesome(?) 90s gaming hip-hop music

Ahh, the early 90s. It was, indeed, time for Klax, but also time for a sharp rise in popularity of rap and hip-hop music. Anyone who was a kid watching cartoons on North American TV during the late 80s and early 90s was well aware of how companies quite cynically exploited hip hop music and culture to look “cool” and “with it” to the youth. We got all manner of terrible faux-rap theme songs, new and improved character designs with backwards baseball caps, and some of the most hilariously awful commercials ever transmitted through the airwaves.

Game companies were no exception when it came to utilizing hip-hop’s popularity for commercial means, with predictably bad results.

(To be fair, Nintendo would eventually improve Zelda rapping significantly.)

Making a commercial with a rap theme song was one thing, but taking inspiration from hip-hop and combining it with game music was something else entirely. The rapidly improving sound quality of VGM, bolstered by the introduction of CD-ROM redbook audio, gave enterprising game music composers the ability to implement things like samples and voice into their songs, allowing for them to create original rap and hip-hop tunes for games. The songs were still predominantly hilariously bad, of course, but there’s a weird and lovable kitsch to them that makes them incredibly fun to look back on. Most of them, anyway.

So today, we’re going to be looking at several of these awkward game-related attempts at jumping on a musical fad. I’ll be leaving out one really obvious track – the Street Fighter III Third Strike character select theme – since we featured it previously. (I’m also leaving out Parappa because it’s just too obvious.) Everything else on here should hopefully either jog memories or be completely new to you lovely readers. So put on your Reebok Pumps and bootleg streetwise Looney Tunes shirts, and get ready for a game music time warp!

Interview: Donna Burke, veteran singer and voice actor

Remember watching that Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain trailer that was unveiled at E3 2013? Do you remember first hearing those sweeping, powerful notes of the game’s vocal theme, Sins of the Father? I bet you do. But how much do you know about the amazing voice behind that and the Peace Walker vocal theme, Heaven’s Divide?

You might be surprised to find out that Donna Burke, the vocalist behind those two songs – and the voice of the in-game IDroid – has a very long and storied history doing English voices and musical work for numerous games from within Japan. Her list of previous projects includes numerous classics and fan favorites, and through her music and talent agency Dagmusic – which she owns and manages – she continues to provide the Japanese game industry with valuable voiceover and sound services.

I had the opportunity to talk with Donna about her past and previous work, how she came to Japan, what the English voiceover industry in Japan is like, all those different English accents, and – of course – those amazing Metal Gear songs. Read on!

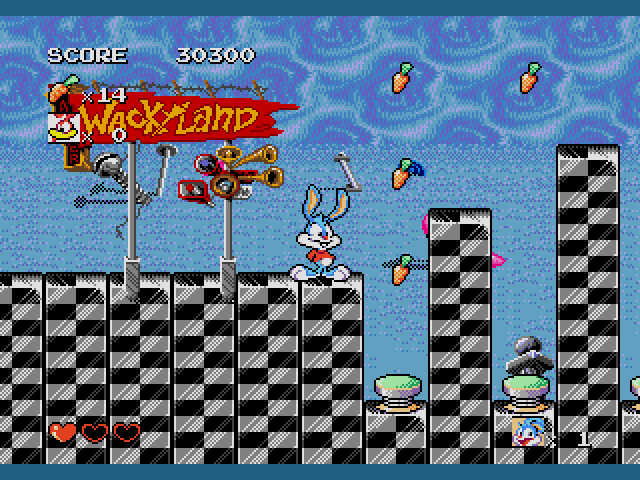

Play it Again for the First Time: Buster’s Hidden Treasure (Konami, MegaDrive, 1993)

An experience I think many have had is revisiting a game that we had memories of playing in our youth. While we all had those games that we had essentially memorized – I know stuff like Super Mario Bros. 3 and Sonic 2 so well that the ten-year-old me in my head gets actively angry when I see people not taking bonus-optimized paths through them – there are others where the memories are a little more vague. We enjoyed them at the time, but we’ve essentially forgotten the vast majority of the experience, to the point where replaying the games is like enjoying something completely new. Sometimes it’s a harsh lesson in reality, as you find out that game from your youth was utter garbage you liked because you were young, dumb and ate up anything with your favorite characters on the box. Other times, you find yourself rediscovering what you enjoyed so much, and perhaps even appreciating these titles in a brand new way through the eyes of experience.

So there’s a series of podcasts and media under the collective banner of Laser Time that I’m fond of. Most of the folks doing shows and articles there are previous or current employees of Future Publishing (whom I’ve done a fair bit of professional work for), who run the show as a way to talk about interesting pop-culture things and their own subjects of interest with friends they came to connect with through work. Laser Time manager Chris Antista recently did some stuff about Tiny Toon Adventures videogames, highlighting the many titles Konami (and others) published with the license. Among them is the Genesis/MegaDrive entry, Buster’s Hidden Treasure.

Buster’s Hidden Treasure was actually among the first games I got for the Genesis, and I remember spending way too much time defending it against my SNES-owning friends who insisted on the superiority of Buster Busts Loose as a game. It wasn’t uncommon in the 16-bit era for different platforms to get entirely different titles in a franchise or license, and Konami in particular made very, very different games for the SNES and the MegaDrive. So since you couldn’t argue over which had the better framerate or textures, you had to fight over what game was actually better, and boy did I fight tooth and nail for this one. But was I actually right, or was I just doing my duty as a pre-adolescent console warrior?

I wanted to find out. I played Buster’s Hidden Treasure again, and I’ve got a fair bit to say about it 20-some years later.

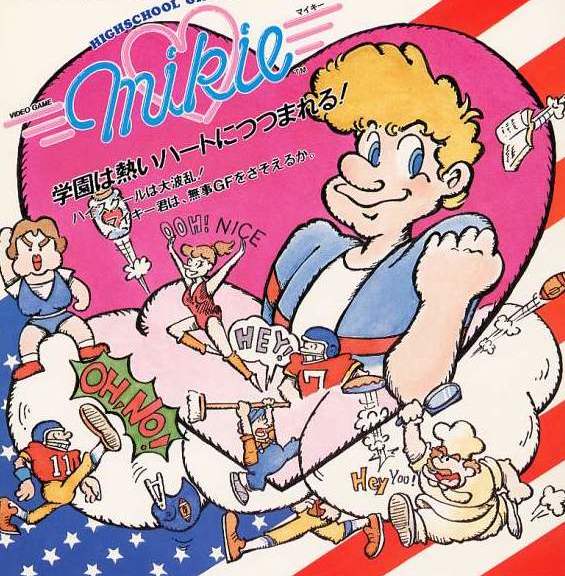

Mikie (Konami, arcade, 1984)

One of the best thing about the early-80s worldwide arcade boom was the sheer creativity exhibited in the concepts. The youth of the gaming medium meant that developers would try anything and everything looking for the next megahit. I mean, yeah, there were definitely a lot of alien-shooty spaceship games, but there was also stuff that you’d have a hell of a time trying to pitch to corporate higher-ups nowadays. (“I mean, yeah, the space marine FPS is a safe bet, but I’ve got something even cooler! Imagine a game where you’re fighting against another guy, with a lance, and you’re riding an ostrich, just kind of flapping around this weird space-time void! Wouldn’t that be awesome? It’ll sell MILLIONS!”)

Technical limitations also forced games to veer away from realism into realms of strangeness and abstraction. Even games that had a setting based in some matter of reality would have to rewrite “rules” in order to make them into something that would make a (theoretically) fun game. Clearly this was the problem facing the Japanese programmers at Konami when they decided they wanted to make a game about American high school life. Not only did these guys have zero actual experience in American high schools, but what the hell kind of game could you make out of that? After much deliberation, it was decided to focus on the major element of high school everyone remembers: terrible people in highly visible and obnoxiously dramatic teenage relationships.

So now, let’s take a look at this very early Konami arcade game, one that puts us in the shoes of Mikie, high school asshole extraordinaire.

–

–