Man, 2018 was quite a year for games, wasn’t it? Of course, it felt like everything amazing got overshadowed by The Cowboy Game coming out at the tail end of the year. You know, the game where if you dare to say anything slightly negative about it, a horde of people was come in and shit up your comments and Twitter mentions.

I mean, clearly the game is amazing, right? After all, no other game this year had as much CONTENT as Cowboy Game. A huge, explorable world! Numerous player and NPC interactions! Realistic horse testicles that some poor graphics rigger in crunch time likely had to miss his daughter’s birthday party to create!

But it’s like… whenever I hear someone I know talk about Cowboy Game, they never seem to be having that much fun with it. They want to play it because it’s the current gaming zeitgeist, but when they talk about doing stuff in the game, it’s never with the sort of excited fervor you hear when someone is describing something they are really, truly passionate about. It just feels like they’re experiencing The Game With the Most CONTENT because that’s what you’re supposed to do unless you want your gamer cred to be shot. Sometimes I wonder if all the vocal fans are genuinely enjoying that game, or convincing themselves that they are (and posting incessantly about it) because they feel like they have to.

There’s so much “well, everything about playing this kind of sucks, and the structure is bad, but if you bear with it for 40 hours…” you’d think they were talking about Final Fantasy 13 during the height of that game’s fan rage

— JEFF♪♪@TIRED (@botoggle) December 30, 2018

CONTENT, in all caps, is what I think of when you’ve got a game that just has a lot of stuff in it for no reason other than to make the game bigger, longer, more epic!!!1! Open world games are often the ones that feel the most CONTENT bloat, but they’re certainly not the only ones: we’ve all played a JRPG that went way overboard with the sidequests, an action game with levels that are pure padding, and tacked-on systems like crafting, levelling, and skill trees in games that don’t really need them. CONTENT is, theoretically, supposed to keep you engaged, but often does the opposite: it wears you down, leaves you longing to get back to the fun parts, and can even make you feel spiteful towards a game for wasting your time with unsatisfying, superfluous empty bullshit.

So folks, let’s talk a bit about CONTENT, why it’s present in games, and how games can be better about giving the player a lot of stuff.

Let me spell out my main point here as cleanly as possible: A game that has more CONTENT crammed into it is not necessarily a better game. In fact, oftentimes the addition of CONTENT actively makes a game worse.

The justification for haphazardly shoveling CONTENT into a game is often to “add value,” but think of it this way: is a mediocre three hour movie the drags in the middle necessarily better than a brisk 90-minute film where every shot and bit of dialogue is well done and satisfying? I mean, movie tickets are pricey, and both movies cost the same… so the former should be the better value, right?

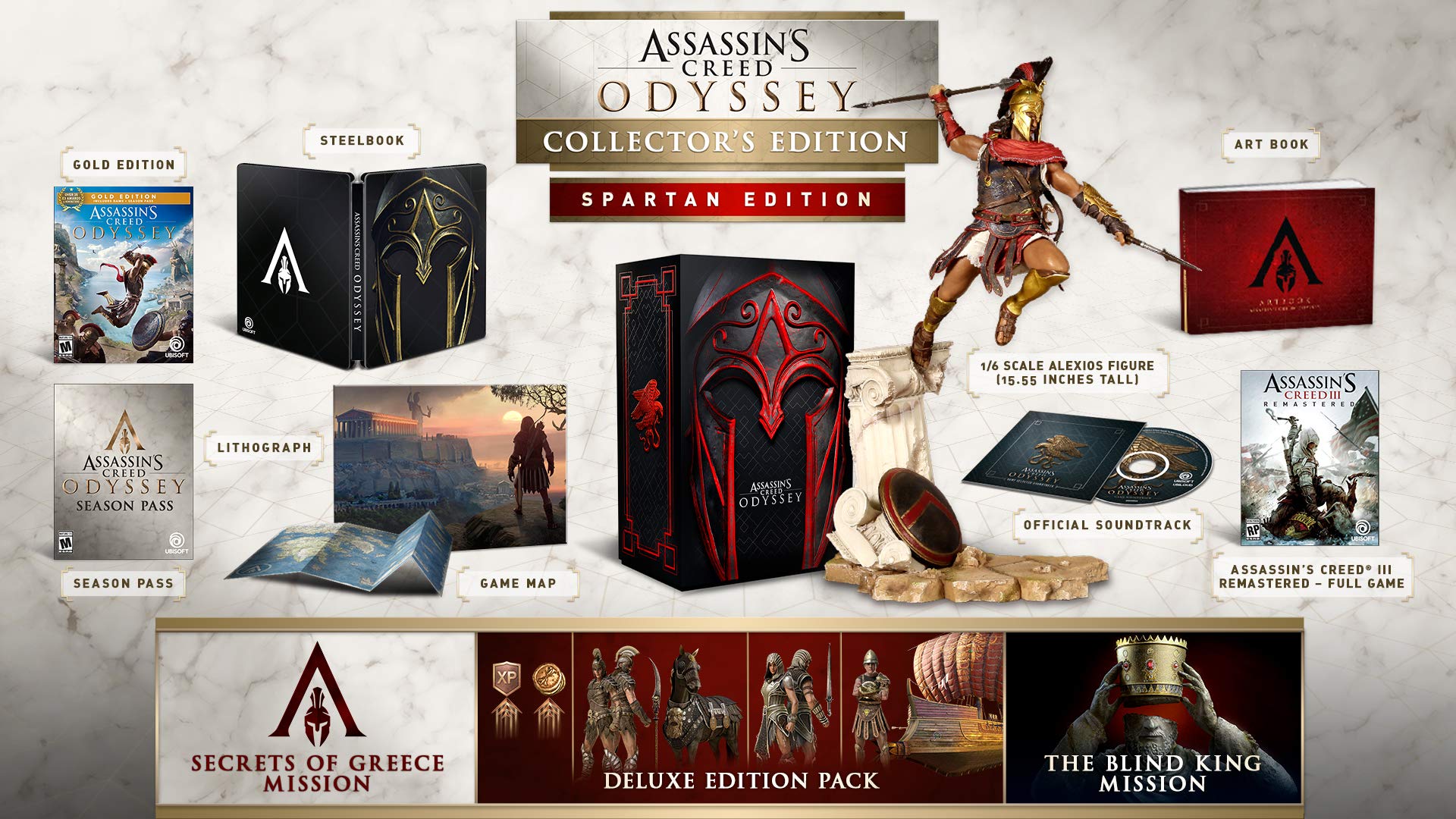

Of course, nobody in their right mind would argue this. Yet, when it comes to games, publishers are so desperate to justify a buyer’s $59.99 purchase that they feel a need to shove as many potential distractions and things to do into the game as possible. There’s no consideration given to the people who have to crunch to get all this CONTENT into the game, no regard to how it affects the overall narrative pacing, it has to be there and there has to be hooks for additional DLC down to line so lucrative season passes can be sold.

As much as I seem to be harping on the AAA game market here, CONTENT creep goes back a long, long way in gaming history. Back when there were Blockbuster Videos on every street corner, developers would often pad out games and jack up the difficulty to try and make sure little Timmy wouldn’t beat the game on a weekend rental.

I think Battletoads for the NES is a good example of this: it’s an overly long game that tries to mix in a bunch of different, not-quite-fully cooked gameplay styles and concepts. While undeniably technically impressive, the lack of focus, overlong length, and soul-crushingly punishing difficulty of Battletoads makes the game feel like less than what it could be. I’d have rather played a game that built on the foundation of the beat-em-up/platforming style from the beginning stage across several levels rather than the jarring, frustrating gameplay style changes Battletoads frequently uses. And god, it really is just so very long.

I think the first time I really started hearing folks complain loudly about an excess of CONTENT was the collectathon platformer invasion of the late 90s and early aughts. Rare’s N64 fare is the best example of this1, forcing players to trudge across massive maps in order to acquire about a bazillion different types of macguffins in various ways in order to progress and complete areas. Donkey Kong 64 was perhaps the nadir of this particular sort of platformer: I remember a lot of folks online dragging it back in the day, and — apart from the DK Rap — it still doesn’t have a particularly great reputation today.

Even arcade games, which are made to be short, weren’t immune from the curse of CONTENT. Metal Slug 3 is a beautifully animated, incredibly imaginative game filled with branching paths, crazy enemies, weird humor, and challenging run-and-gun action. It’s also a game where the final level takes up about half of the game’s playtime, forces you through scrolling shooter sections that are way too long for their own good, has several incredibly slow and tedious sequences, and wears out its goodwill at about the forty-minute mark. It’s an amazing game to witness, but by the end, you really just want the damn thing to wrap up.

Nowadays, though, things are different, and the push for CONTENT is stronger than ever. Game budgets have ballooned, and while the rental market has mostly died off, used games still cut into potential publisher profit margins. In order to convince people not to sell their games back to GameStop after a week, publishers are convinced that CONTENT is one key to stop the used game market: give the player more stuff to do, and they’ll play the game longer — not realizing that when that content isn’t enjoyable, it actually makes the player dislike the game more.

But I don’t want to spend this whole article being a negative nelly. I’d like to highlight a few recent games that are packed with stuff — and manage to do it well.

For starters, there’s the Yakuza franchise. Now, compared to other open-world style games, Yakuza is significantly more restrictive: the environment(s) you explore is smaller, you can’t interact with people or the environment in freeform ways that cause wanton destruction (or, in the words of localization producer Scott Strichart, “there’s no ‘do crimes’ button”), and the movement of Kiryu (or, depending on the game, another protagonist) outside of combat or side events is limited to walking and simple interaction with a limited number of objects and people.

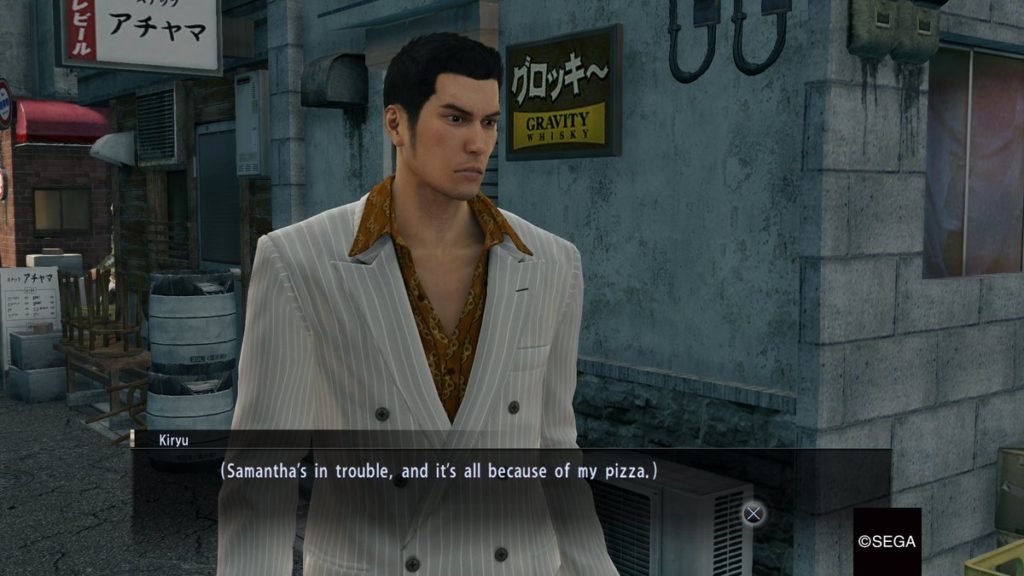

But this sort of restrictiveness is actually a boon in disguise. For starters, it helps establish the character of Kiryu by portraying his moral code through gameplay: he doesn’t commit random acts of crime, only fights when provoked first, and has a soft spot for helping people in a bind. If Kiryu could just trash environments and punch whoever whenever the player felt like it, it would be at completely at odds with his character as presented in the story sequences.

Even more importantly, however, the limited exploration and environment interaction helps to lead players things like the various substories and the mini-games with minimal distraction. These character interactions and mini-games have a tremendous amount of care and effort put into them, thanks to the development team not being completely stretched thin by trying to make realistic, interactive environments. People remember things like the dominatrix and pizza side stories and the hostess club management of Yakuza 0 because they were all humorous, fun, and engaging. Being able to put a lot of effort into select content and carefully leading a player to it, rather than stretching a development team thin making a myriad of uninteresting distractions, makes all the difference — and it’s part of why the Yakuza series has really been building an audience in the West recently.

One game I reviewed this year was Dragon Quest XI, which I loved a lot. Of course, it’s not a short game in the slightest: you’ll probably put about 60-80 hours into it when all’s said and done. Yet one thing I was really surprised with was how well DQXI managed to keep its pacing throughout its lengthy playtime. As soon as a locale or a substory starts to wear thin, the developers seem to know exactly when it’s time to toss in a big, challenging battle or a narrative-advancing event to scoot things along to the next exotic locale. There are plenty of side distractions, but none of them feel like drudgework: in fact, you can complete a good chunk of the NPC-request sidequests by simply taking a few minutes to farm enemies or look for a specific location while you progress normally through the game. Even the grindy casino games have an option to simply set the slots to auto-play, as if to acknowledge “look, we know some of you are completionists but don’t find this particularly fun, so we’ll let you go do something else while this runs.” This is, honestly, one of the best-paced games I’ve played in a while, both in terms of its overall narrative and how it doles out extra activities for the player to partake in.

Let me diverge from the topic of CONTENT a little bit here. In recent times, it’s become pretty common to reuse assets from one game to another: background objects, character models, generally expensive-to-produce-from-scratch-all-the-time art assets. While some folks like to bash this under the pretext of the developer being “lazy,” most of the time that’s not the case: for efficiency and costs’ sake, if you have something that works well (maybe with some minor tweaking) and there’s no good reason not to reuse it, it just makes practical sense. Asset reuse lets the graphics team put more effort into making the new graphical assets that need creating even better. This isn’t a new thing in modern game development, either: your average 16-bit RPG had about five palette swaps for every enemy sprite, and beloved FGC staple Marvel vs. Capcom 2 is basically 85% recycled character animation.

Yes, plenty of games have reused assets to good results, but not always: when you get cases like the infamous Morrigan Sprite in the early 00s, it starts to look really bad.

But what does this have to do with CONTENT? Well, I’ve found that sometimes, when a developer finds interesting ways to recycle existing assets, they can create some genuinely fun content.

One such example is Darius Burst Chronicle Saviours. There are literally thousands of unlockable stages in this game across AC and CS modes, and with that many variations, it’s obvious enemies, bosses, backgrounds, formations, and such are going to be reused and reused a lot. And that doesn’t affect the game in the slightest: it’s a wonderfully done shooter where every boss you fight is a treacherous battle of dodges and counters and every stage is filled with obstacles to avoid and power-ups to grab to attempt to make that boss encounter maybe a little bit easier.

And then there’s Super Smash Bros. Ultimate. Now, I find that World of Light (the game’s adventure mode) is rather divisive — you either like it a lot or you find the constant string of battles it offers quite tedious. Me? I love it. It’s neat to see that way the development team chose to represent elements and characters from across various games using the available cast, assist trophies, and all the crazy combat events that can happen. This, to me, is another good use of “recycled” content — they didn’t make any new characters (besides bosses) for this mode. Heck, they didn’t even make new trophies — all of the “spirits” you collect are PNGs of key art from across various games. But as someone who likes a lot of different games, I enjoyed the gimmicky spirit battles and how they tied in to other titles a lot. A game like Smash requires an absolutely absurd amount of effort and development time even with a lot of asset reuse, and I feel like the Spirit battles were a good way to represent a variety of games, reuse character and background assets, and give the player interesting gameplay variants.

So there you go: four recent games that have plenty of stuff, much of which benefits the game and enhances the package while not going overboard and wearing the player (and possibly the dev team) out. There are plenty of other examples out there, too, and I’d love for this piece to spark a conversation on what games felt “just right” for you in this regard.

- Man, it feels like I really have a Rare hate-on, huh? Well, honestly… yeah. Never was a fan. ↩

Ironically it seems Rare’s most recent game suffered from the opposite problem, and there just wasn’t enough to do in Sea of Thieves. (Though I do hear about free content expansions every so often since release.)

To Murlin – I feel like Rare assumed that the fun in Sea of Thieves would be emergent gameplay, like with other bare-bones games like Rust, ARK, and PUBG. Alas, it appears that they were wrong.

I agree almost 100% with this blog. I recently played through metal gear solid 5 and FarCry 5, and I had to rate them significantly lower because of all the garbage shoveled in. If either game was a concise experience instead of having 500 side quests that sucked I would have been a lot happier

It’s like I have agoraphobia playing the cowboy game. Didn’t had that issue with Zelda BotW or GTA5 at all. Great article btw, Heidi

>”they never seem to be having that much fun with it.”

These are joyless games. When i watch people play these i see frustration and anger in their faces, never joy. The measure of a ‘great’ game these days is in sold units alone. And social peer pressure has replaced solid game play. And it works like a charm. Especially for a company like rockstar who sells in the millions.

My favorite example for massive amounts of content done right is Divinity Original Sin 2. There’s just soooooo much to do in the game, and all of it is fun, fleshed out, often hidden in places you really need to go out of your way to explore.

It took me about 150hs to do pretty much everything in a playthrough, and I never found myself thinking “man when does this wrap up”… rather, “oh man I’m going to be so sad when I finally beat this, I want even MORE!”.