(日本語版はここです。) La traduction française est ici.

One of the biggest names in classic game music – and one that persists to this day – is Taito’s house band/music production arm, Zuntata. Among the many storied composers who have worked for Zuntata over the decades is Hisayoshi Ogura, known to fans of the group as OGR. Ogura and his avant-garde game music was crucial in establishing Zuntata as one of the pioneers of arcade sound design with soundtracks like the Darius series, Ninja Warriors, The Legend of Kage, and Galactic Storm.

I’ve been a huge fan of Ogura’s work for a very long time, and I’m elated to finally have the opportunity to talk with him about his amazing body of work and present it to readers. Ogura’s compositions don’t get quite as much admiration in North America as they do in Japan and Europe, and I hope by bringing awareness to his work through this interview that more people will listen to his amazing classic game music. (To that end, I’ve included links to iTunes and Amazon music stores in places to help facilitate the acquisition of soundtracks he’s worked on!)

Very special thanks to Zekuu for helping to arrange this interview, along with Jason Moses and Feelwright and Co. for helping with translation/editing.

What lead you into a career in music, and specifically, to Taito?

Ogura: I admired the famous Japanese composer Kyohei Tsutsumi and wanted to become someone who, like him, was capable of challenging musical norms and being really experimental. I also wanted to create pop music.

What led me to Taito was an employment ad in the newspaper. I‘d been planning to apply to either Namco or Taito, whichever posted a job first. Taito turned out to be the first.

What was the game music scene like around the time you joined the company?

Ogura: It wasn’t the greatest—speaking purely as a musician, of course. I have to emphasize that’s from the perspective of a musician like myself, though.

The keyboard Taito furnished me with at the time was your basic family-use model, and programming the music data for games entailed a highly specialized system that used hexadecimal input. It did get better over time, though.

Namco’s game music was very popular at the time, and there were a lot of fans of the company’s work within Taito.

The mid-80s saw a lot of well-known game music composers start to earn recognition. Did you ever talk to your peers in the field at the time?

Ogura: I had very few opportunities to speak with composers from other companies. And since the development environment and policies varied across the industry, I never had a particularly strong desire to do so.

What inspired the creation of “Zuntata” as a sort of “house band” for Taito?

Ogura: There was this producer at a record company that handled game music at the time, and his ideas had a lot to do with the birth of Zuntata. He told me, “Wouldn’t it be more inspiring to [make music] like you guys were a really a band?” Plus, other sound teams had adopted the band model already.

It’s true that I was credited as Zuntata on the album for Darius, but at the time I figured it was just going to be a temporary unit that only existed for that album. I never imagined Zuntata was going to get as popular as it did.

The first Zuntata logo, on very early albums.

The first Zuntata logo, on very early albums.

What were some of the earliest games you scored at Taito?

Ogura: One early game I composed everything for was a maze game called Outer Zone. The score was clearly influenced by techno music from the time period. I also experimented with playing a jingle when the player inserted a coin instead of just sound effects.

(Outer Zone is very rare – it doesn’t appear on any Taito collections, and is unemulated.)

I feel as though Darius was your breakout score. It sounds different from a lot of game music that came before it, using uneven melodies and unusual instruments to create a soundtrack that is both moody and memorable. Can you describe what you were trying to accomplish with Darius’s music?

Ogura: Darius’ big theme was “an enormous entity lurking within the universe.” At the time, there was nothing I could call a concrete concept backing up what I was creating, just an image. I think the game’s main theme, “CHAOS,” is what really ties the soundtrack together as a whole and gives it balance.

At the time, it was pretty adventurous to use avant-garde rhythms and irregular meter in game music, but I remember telling one of my juniors at the company that “a few years from now, this kind of thing will be everywhere,” so… I mean, I think I just wanted to destroy something, and saw Darius as an opportunity to wipe out what was considered common sense in game music at the time and recreate things from the ground up.

The track “Daddy Mulk” in Ninja Warriors was one of the first game music tracks I can think of to make heavy use of a voice sample. What inspired this song? Also, why did you include a shamisen solo?

Ogura: I used sampling in “CHAOS” (from Darius) and a few other songs. The quality was only 8k though, so it sounded a little rough.

For The Ninja Warriors, I ended up using a shamisen because the timing was right. The specific instrument used is known as a tsugaru shamisen, which I’d always felt an intense sort of attraction to. I really wanted to use it in a game, and when I found out that Ninja Warriors would be using a Yamaha sound chip with high-quality sampling capabilities, I knew the time was right.

I remember talking to one of the game’s planners while looking at images from the game, and him asking me to create “music that would stand out.” I asked him if it was really okay to push the limits and make something outstanding, and his reply was “yes.” I also have memories of these bizarre ninja movies becoming all the rage in America, and from a Japanese POV the characters in the movies barely resembled ninja at all. That was the perspective that gave birth to the music you hear in the game: a strange combination of pure Japanese sounds (the shamisen solo) and modern band sounds (the synth solo) that formed the basis for the main theme: “Daddy Mulk”.

The original arcade release of Rainbow Islands with its original music.

The later PS port/remake, one of many with altered main music.

Rainbow Islands famously had its main melody altered in Western console ports and later re-releases. Do you know if this was done due to copyright concerns?

Ogura: I’ve heard it was a copyright issue. I was involved in a lot of games and the time and don’t remember the details especially clearly, so I honestly don’t know whether a subcontracted composer intentionally imitated an existing song. Either way, the fact that the situation played out the way it did was the result of carelessness on the part of the entire sound team, including myself.

The title music to Metal Soldier Isaac II

The 1985 Taito arcade game Metal Soldier Isaac II features a song that sounds like an early version of Captain Neo from Darius. What’s the story behind this?

Ogura: Darius needed music for a game show appearance, but I didn’t have time to write anything specifically for it. I proposed porting Captain Neo from Isaac II and we immediately set about converting the song. The person in charge of conversion at the time was a new hire by the name of Masahiko Takaki (aka MAR, who would go on to compose games like Rastan and Night Striker), and I directed the process. The converted version was pretty rough, but it had this feral quality to it that I wouldn’t have been able to produce, so I decided to use it in Darius as is. So as a piece of music, it’s the same as the one in Isaac II.

One of your soundtracks that I feel isn’t as well-known as it should be is your fantastic score for Galactic Storm. Can you tell us a bit about that game and what you were going for with your compositions? What is your favorite track?

Ogura: Galactic Storm was a very memorable assignment. The planner and I created a story, an epic and poignant tale. Whenever we’d think of something new, we’d call each other (the planner was in Osaka and I was back at Taito’s main lab in Yokohama)1), developing the story over time. Using Jung’s idea of complexes as the key concept, I finally started composing.

The story in its visual form was always on my mind, and I would compose the music bit by bit as I watched the story play out inside my head. Composing the main theme, “Prot Mind,” took that much more care for having internalized so concrete and complete an image of the story. I ended up spending days writing and rewriting the 2 bar section in the middle. That’s why “Prot Mind” is my favorite song on the soundtrack.

Zuntata put on a lot of live shows during the late 80s and early 90s. What were these shows like? I’ve only ever seen them through old video footage, and I really wonder what it felt like to perform in them.

Ogura: Zuntata’s first live show was in 1990. Everything about it was handmade, and everything was a new experience for me. Ordering the band’s outfits, ordering the scenario, arranging all the songs for live performance—I can keep listing the firsts. We were deciding on the set list while revising songs, adding new elements and meaning to them along the way. In the end, with everyone pulling their weight, we somehow managed to get everything ready in time.

We would go on to add more story elements, coupling images with our music, and further developing the story aspect, but I’ll always remember that first and toughest gig we did in 1990.

https://youtu.be/45D4jyKqcPA

A clip from Zuntata’s 1990 concert.

Many developers created in-house sound units during the late 80s and early 90s – S.S.T. Band, Alph Lyra, Gamadelic – but only a few survived past that time period. They put on a lot of live shows, as well. Why do you think they faded away?

Ogura: Hm, I don’t know why those other bands faded away, but I can talk a little bit about why Zuntata’s still around. What we prioritized the most was branding, and that meant we were pretty strict at times. For example, even for music created by members of Zuntata, we looked at whether to release it under the Zuntata name, or simply under Taito. That’s how we sorted out whether it met a certain quality standard or not. I don’t mean like, “Oh, this isn’t very polished as a piece of music, so it’s not a Zuntata work”— it was more about whether it had a certain ambiance or not..

This might have been unpleasant for the composers, but I wonder if strict rules like this were the reason we were able to gain brand recognition.

The important thing is that this kind of creative DNA is being passed on, even to this day.

Darius Gaiden is my favorite game soundtrack of all time. I remember hearing the opening track, VIZIONNERZ, for the first time and being amazed at the emotions it stirred within me. Can you tell me what you wanted to accomplish with this song?

Ogura: Darius Gaiden was created based on a concept that had roots in Jung’s idea of archetypes. For “VISIONNERZ,” I took lyrics that read, “Truth isn’t what lies in front of you. Truth lies elsewhere” and had them sung in an operatic fashion. I think that makes it a rarity among my works; not many of my songs have a concrete concept like that within the work itself. Put succinctly, “VISIONNERZ” is the collapse of the ego given musical form.

If you were looking at something and it changed in front of your eyes, and you suddenly realized that everything you thought was an indisputable truth a second ago wasn’t true at all, that would be a considerable shock to you. People in such situations would be unable to maintain their composure. They’d start to break down mentally. That’s the kind of concept I wanted to convey through “VISIONNERZ” and the music of Darius Gaiden.

Did this game you saw called Darius Gaiden truly exist? I wonder…

As a listener, I feel as though the music in each Darius game you’ve scored follows a theme: the original Darius is a dangerous journey to an unknown place, Darius II is a voyage to return home, Darius Gaiden is very dreamlike, and G Darius is very tempestuous – it oscillates between being quiet and being very loud. I’m wondering if my assessments are akin to what you had in mind when composing… or if I’m totally off the mark, haha.

Ogura: Everyone has their own image of something and everyone has different ways of expressing themselves, so whether they’re on the mark or not seems like a non-issue to me. What makes me happy is the fact that you felt the thematic nature of each title. I’m several hundred times happier hearing that, rather than feedback about indefinable badassness or vague sense of epic scale.

But I know you won’t be content with that answer, so I’ll say this: all of the themes you sensed were part of the concepts I used when creating the music for those games. So no, you’re not off the mark.

You’ve done some projects outside of game music in your career that aren’t quite as well-known. Can you tell us a little bit about those?

Ogura: There really aren’t a lot of them. The only thing I can think of would be the soundtrack I created for the Darius Gaiden image drama (Zuntata Visual Clip Vol. 2: Darius Gaiden), which was a lot of fun to work on.

I had a little TV next to my keyboard, and made timing adjustments to the music based on the clips they gave me. Actually, I remember misunderstanding the schedule they provided, thinking I had way more time until deadline than I actually did – in reality, the audio post-production was mere days away! The director probably thought, “He must have misunderstood the schedule,” so he called me up and gave me the correct deadline. I’m still very grateful to the director for that. I dove into composition work and somehow managed to finish in time.

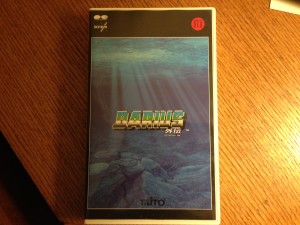

Above: my copy of Zuntata Visual Clip Vol.2

Zuntata’s output seemed to decrease significantly in the 2000s. What were the reasons behind this?

Ogura: I think it’s because Zuntata became heavily involved in a certain kind of content production as a result of the widespread use of mobile phones. (I feel that the company itself was losing the ability to make games). That led to us concentrating on sound work for mobile content. In fact, that was an era [so troubled that] composers were doing content planning itself. But I actually think that was a good experience for me.

When did you decide to leave Taito and go freelance?

Ogura: Draw what conclusions you will from the above answer. I can’t say much, because I love and am proud of Taito.

Can you tell us a bit about your current projects?

Ogura: Most recently, I was working with fellow artist and friend, ekotumi, to arrange a song that was sung and performed in front of 5,000 guests at Japan Expo 2015 in Paris.

You did music for an iOS shooter called Vectros. How was the experience? Since mobile game designs varies from that of consoles or arcade games, did you take a different approach to composition as well?

Ogura: iOS games used a waveform system for music and sound effect playback, so it was painless work. The only issue was size restrictions, which forced a drop in sampling rate for everything other than the main theme, but I have plenty of experience dealing with that kind of thing working on arcade games, so that wasn’t particularly uncomfortable.

The concept I went with was a stark one, which is something of a rarity for me: “Geniuses are errors.” To put it bluntly, I was singling out scientists, inventors and even the people around them who seek to own and profit from their discoveries, for criticism. There are plenty of innovations society probably would have been better off without, after all. Nuclear power might be one. So in that sense, the world is full of “errors”.

For the main theme “SiLent ErRors,” I used sounds from real-life incidents in much the same way I would use synth sounds. I’ve taken things that ought not to exist into my music, and you can consider that my message to the world: “The world is full of errors.”

You also did some music for Minna de Mamotte Kishi (Protect Me Knight 2). I’ve listened to it, and it really… “feels” like something you’d compose, haha. The game was developed by Yuzo Koshiro’s studio Ancient – and Yuzo was one of your contemporaries in advancing game music into an art in the 80s. What was it like working with him on this project?

Ogura: It was a very enjoyable, very happy, undertaking, because it’s a very different thing for me to be asked to work on a project by someone I don’t already share a friendship with.

I’ve done more shooting game soundtracks than anything else. Don’t you think so? That’s why the process of putting music to such a cute, 8-bit-style game was a wonderful experience for me, and I’m grateful to Yuzo Koshiro for giving me the opportunity.

How do you feel about the current state of video game music? What do you like and dislike about it?

Ogura: Sadly, I don’t listen to game music, because with a few exceptions, I don’t enjoy playing games. I treat them as a visual medium. They’re something I view rather than play. Thus, when composing music, I think about what approach I should take musically not in regard to games, but in regard to visual media.

That said, if you’ll allow me to offer my thoughts on the matter, it feels like everything is being glossed over by orchestral sounds. Don’t misunderstand me, I’m not attacking composers. It’s a more fundamental problem than that. It’s about whether game creators want to make games or mock-movies.

Movies have specialized staff, often with decades of accumulated experience. When game creators take a movie scene we vaguely recognize (including the music), imitate it with all the clumsiness of a novice, and drop it into a game, it’s only going to look cheesy and irritate players. Don’t you think?

What are your future plans at this time? Can you announce anything you’re working on?

Ogura: I’m working on the second entry in my original album series, which will follow-up the first entry, “Fukan Shita Jijitsu to Kyakkanteki na Kyokou – Kono Futatsu de Boku wa Sekai o Tsukuru – MMXV-I (Reality from a Birds’ Eye View and Objective Pretense: With These Two Will I Make a World: MMXV-I).” I also have lots of other things I have to work on, but unfortunately I can’t give any specific release dates at this time. The only thing I can tell you is that it’s definitely going to be some interesting compositions.

- I asked John Andersen, who knows an absurd amount of details about old locales of Japanese game developers, about this – according to him, there were two Taito development labs in Tsunashima, Yokohama, one that focused on consumer games (that also housed Zuntata) and another that held some arcade development staff. ↩

Great interview! I think getting in contact with Takaki would be cool also.

Ohhhh man, thanks for including so many good links! Now I need to buy the Silent Errors mp3, the amazingly titled “Reality from a Birds’ Eye View and Objective Pretense: With These Two Will I Make a World” album, and figure out a way to buy the Mamotte Knight 2 soundtrack lol

This was an excellent interview. I’m really glad you touched on the thematic elements of the OSTs. As well, it’s wonderful to hear his process towards composing broken down.

Thanks for this!

Thank you for such an excellent interview!