Much as I take pride in my knowledge of gaming history, there are a few areas that I could stand to learn more about. One company whose history I don’t particularly know that well – though I’ve always meant to learn more about – was Human, a Japanese developer and publisher prominent through the late 80’s up until the end of the 32-bit era. Human was known for a lot of things: Fire Pro Wrestling (perhaps the best-regarded wrestling game series of its time), a game design school that produced fascinating experimental titles like The Firemen and Septentrion (S.O.S. in the West), the groundbreaking Clock Tower series, and a sudden collapse that left the firm in shambles.

So when I was offered the opportunity to conduct an interview with Hifumi Kono, the former Human employee who went on to found developer Nude Maker, I jumped at the chance. I was eager not only to learn a bit more about Human’s history, but also to look a bit deeper into the game that defined the company’s later legacy, the Clock Tower horror game series, and its spiritual successor Project Scissors/NightCry. Read on for a candid look at Human’s past, Clock Tower’s influence and how it symbiotically benefited from Biohazard, living on pachinko earnings, and what happens when you play a classic Western horror game without speaking the language.

Hello, Kouno-san. I have one fairly obvious question I’d like to get out of the way: why is your company called “Nude Maker?”

Because I work in the nude all the time. *laughs*

Uhhhh…

*laughs* Actually, no, it’s a completely different reasoning. In this industry, people tend to dress themselves up with a lot of titles and accomplishments. I wanted to get rid of that, and focus on creating great games regardless of who’s involved. In that sense, I’m “nude” – nothing decorates me, I’m just Hifumi Kono who makes games.

So how did you first get into game development?

My first experience in anything having to do with games was making a card game in college. It was a simple game, just drawings on cardboard, based on the Yakuza. You’d become a member of a Yakuza family, expand your reach, and try to run the other families out so that your family would dominate. My classmates really liked it, and the joy I felt seeing others have fun with something I made – that was the biggest thing for me.

Since your first experience in game creation was in tabletop games, what lead you into the electronic gaming field?

One of the biggest challenges with tabletop game design is that having other people to play with is practically required. Videogames, in contrast, have a built-in opponent. As a person who grew up playing arcade games, I felt strongly that videogames were the future of the medium.

How’d you wind up transitioning into videogame development, then?

I’d done some experimentation with BASIC in my spare time. I was actually an economics major in college, and I had planned to become an accountant when I graduated. After seeing the success of my self-made game, however, I decided on a whim to send off some resumes to gaming companies. I bought some gaming magazines and looked for the addresses of companies doing recruiting. I sent out resumes to all of them, and the only one that got back to me was Human. That’s how I got in. This was around 1991.

So Human had been around a while by that point. I’m trying to remember what in particular they were pushing at that time. What was the first thing you worked on when you joined the company?

I worked as director on Human Grand Prix 2.

Above: F1 Pole Position, the Western release of Human Grand Prix II.

I seem to recall Human making a lot of really interesting, unconventional stuff around that time, too – games like The Firemen and Septentrion (S.O.S). What was the development atmosphere at Human like at the time?

In modern game development, you’ll see a lot of teams sitting together, regardless of what their specialty is. Human Entertainment, however, was laid out so that, for example, all the planners would sit in one place. Artists, programmers, sound people were also grouped this way. They’d all be separated, rather than just one team sitting together. I recall things like artists not being particularly friendly with one another…

Office politics?

It was different than that. Like, between planners and graphic artists, they couldn’t understand the work the other person was doing throughout the day. Every person thought they were the best in the company. There was a real pride thing going… people just didn’t get along well.

Now I’m wondering just how anything got made in that kind of environment.

Actually, I think it had a positive effect. Because people couldn’t get along and were always arguing, everyone got really passionate and fired up about what they in particular were creating. *laugh*

Interesting way of doing things… so what did you work on at Human besides Clock Tower?

I already mentioned the Human Grand Prix series, but there were two other major titles. One was called Nekozamurai. It literally translates to “cat samurai.”

This was a historical-fantasy adventure game set in old Japan. It didn’t sell very well, sadly.

The other title is Mikagura Shoujo Tanteidan. This game included a gameplay element called the “mystery-solving trigger.” Apparently it had quite an impact on Japanese adventure games that came along later. It was an inspiration for Ace Attorney’s objection system.

(Editor’s note: In the course of research, I discovered that well-known eroge publisher Elf apparently has the rights to Mikagura Shoujo Tanteidan these days. They re-released the old titles and made a new game in the series in 2003 for PC without Human’s involvement. Unsurprisingly for Elf, they also added sex scenes.)

Clock Tower was obviously a breakout hit both for you and for Human. Where and how did you begin working on the title?

Around that time, Human Entertainment’s primary focus was sports games. The sort of games you mentioned earlier, like Septentrion, were actually products of students from the affiliated Human Creative School for game design. So a bunch of us got together and attempted to convince the higher-ups that we wanted to make something besides a sports game. That lead to a competition in-house to determine the best game we could come up with. I came in first, and that’s how work on Clock Tower began.

Very interesting – any idea what the other submissions were?

Sadly, I wasn’t able to see the other submissions. Everyone submitted to their bosses, and the pitches were evaluated in a closed environment. I don’t even know who in particular I was competing against.

After Clock Tower proved to be a hit, Human’s regular staff were allowed to create more weird, experimental games on a regular basis.

When Clock Tower was being developed, the 32-bit CD-based consoles had just hit the market. What made you stick with the Super Famicom for Clock Tower?

At the time, Human Entertainment only had pixel artists. There weren’t many 3D artists at the time. In addition, because this wasn’t a sports game, the company viewed it as high-risk. There was no way they were going to hire expensive specialists to make the game for new 3D platforms. That’s why we wound up working on the SFC.

What were your primary inspirations for the game at the time?

I’d have to say my biggest inspiration was Alone in the Dark.

I’m curious, was that game a particularly big hit in Japan? It’s often cited as an inspiration for the first major wave of Japanese horror games, but I’m not sure if it sold too well there.

It really wasn’t too well known in Japan. Not many people knew of it, but one of my colleagues in the company introduced me to it and it wound up having a big effect on me.

Was it even localized into Japanese?

I don’t think it was! I played the English version. I honestly had no idea what the game was about. Because I didn’t really understand the “rules,” so to speak, I was dying constantly, getting pulled into the dark…

So it essentially wound up being a horror-themed Spelunker where you died constantly. *laughs*

*laughs* For the longest time, I thought it was such a hard game to play!

What made you go with a young woman as the Clock Tower protagonist?

That would be the influence of the 80s horror films that I’d been watching. In my mind, the only good horror had female protagonists. It’s also better to see young women screaming than old men screaming.

*laughs* So what in particular inspired the development of Scissorman, the series’ most memorable antagonist?

The direct inspiration is Phenomena, a film by Italian director Dario Argento. Y’know, back then, there were a lot of game characters that conspicuously resembled characters from famous films. I must apologize to Mr. Argento, because I did exactly that!

What do you feel that scissors represent? They’re a pretty prominent element across the series, and are the working title (Project Scissors) for NightCry.

In the original Clock Tower series, the scissors have a strong impact on the player. I wanted to create a sense of dread, of slow pain. The pain you feel with a knife or a gun is instantaneous, but with scissors, you feel the blads closing in, coming against your flesh, taking their sweet time to finish the act. What I really wanted to express was the duration of pain.

That’s both disturbing and very thoughtful.

In Project Scissors, however, the meaning of the imagery is different. In my mind, what scissors represent are the separation of two things, living or no. One of the biggest things I’m focused on in NightCry is that when a human is born, the baby becomes individal as a human being only after the cord is cut. In that sense, scissors are a tool that separates the lives of two different living things. That’s the basis of the game’s scenario.

When the original Clock Tower released in Japan, I don’t think there was as big a furor over violent or potentially disturbing video game content over there. Still, did you run into any issues getting anything past your higher-ups or Nintendo?

Well, there were a few lines I didn’t want to cross personally – I wasn’t going to show things like heads getting cut off or guts spilling all over the place. Clock Tower was a game more about indirect expression of terrifying situations. Because of that, I didn’t really run into any problems with content.

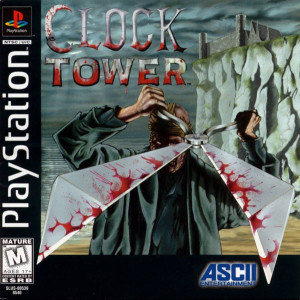

Clock Tower II was released as just “Clock Tower” outside of Japan, and featured amazingly low-key and subtle cover art tailored to Western sensibilities.

Moving on to Clock Tower 2 on the PlayStation – what kind of new potential and challenges did the move up to the Playstation platform deliver?

The team that worked on CT2 was essentially the first team at Human to work on a 3D game engine. The veteran artists insisted on using pixellated art rather than polygons! It was also the first Human title to utilize motion capture. One major thing that 3D allowed me to do was use a larger variety of camera angles… those are the big things I specifically recall from development.

By that point, Capcom had released Biohazard/Resident Evil to massive worldwide success. What sort of effect did this have on development?

Biohazard was announced while we were developing Clock Tower 2. We were amazed at the quality of the visuals Capcom was implementing. It was a challenging goal, but we wanted to one-up Biohazard. Later, when I’d actually get a chance to actually speak to Mikami-san, I was amazed at just how much bigger the Biohazard dev budget was. *laughs*

How were the reception and sales of Clock Tower 2, when compared to the original game?

I felt that we’d really improved the playability of CT2. One thing I also tried to to was implement a bit of psychoanalysis into the game – with those two factors combined, I think we wound up with something that was easier for non-hardcore players to pick up as well. I personally feel like the sequel was accepted by a broader audience. We sold close to half a million copies, but I don’t think we would have reached that number had Biohazard not started a boom in horror games.

Human started to get into serious financial problems towards the end of the 32-bit era. Could you tell us a little bit about what happened to the company?

*laughs* Well, actually… until the end of Human’s lifespan, the consumer games weren’t the problem. The games were turning a healthy profit. The problem was consultants approaching the higher-ups at Human telling them they should look to expand business outside games. The ill-advised expansions lead to all sorts of problems, and eventually they went bankrupt.

What sort of areas did Human try to expand into?

Arcade games, education, and theme parks, off the top of my head.

Theme parks? Really?

Yup. A theme park with dinosaurs. They really were talking with some lousy consultants.

It sure seems like that sort of expansion killed a lot of Japanese developers during that time. I remember one of Compile’s big missteps was trying to get into business software, for example…

Yes, definitely. I can’t say which company, but I know of at least one game developer at the time that was selling mushrooms as a side business for some reason.

Not Nintendo, was it?! *laughs*

*laughs* They use mushrooms in their games. I don’t think they make them!

When you knew that the axe was about to fall, did you have a contingency plan in place, or were you kind of panicked?

My contingency plan was going indie. I’d been planning it for a while, actually, but unfortunately Human was sinking faster than I’d expected and prepared for. I had to abandon ship and establish my own brand.

And that brand was Nude Maker.

Correct! But because I had to leave earlier than anticipated, I didn’t get many projects at first. To earn money to get by, I was playing pachinko.

*laughs* I’m always amazed at how some folks in Japan make a living off of that.

The laws have changed since then, but around that time I could pull in about $4000 a month.

What was the first game you worked on at Nude Maker?

Our first game was Tekki/Steel Battalion for the Xbox. While I was playing pachinko!

So you came up with the concept for that giant controller?

Yes I did!

How did you manage to sell a concept like that to Capcom?

When Mikami-san asked me to pitch a couple ideas, I submitted proposals for a couple of typical action games I thought Capcom would like. But Mikami-san said “these aren’t the kind of games I’m looking for from Hifumi Kono.” So I stuck my hand into my bag and pulled out my single-page pitch that would eventually become Steel Battalion.

I don’t think something like Steel Battalion would have a chance of making it to market today.

Even back then, only Mikami-san believed in bringing that sort of thing to market.

Also, rather ironically, Capcom would go on to publish Clock Tower 3.

Yeah, I didn’t touch that one at all.

It, uh… it shows.

*laughs* Well, the rights were sold to Sunsoft after Human folded. For that game specifically, I believe Sunsoft and Capcom codeveloped it and shared the rights.

Sunsoft, huh… didn’t know they were still that active.

I actually had the opportunity to speak with them prior to the kickoff of Project Scissors. At the moment they’re mostly focused on smartphones and mobile apps. They’re really working hard to create good games.

They’re about the only developer in Nagoya that I know is still around.

Yeah, when I’m traveling cross-country for business I usually try to visit multiple companies. But when I go to Nagoya, the only place I can go is Sunsoft…

Well, back on topic -what kind of difficulties do you face in the current market with getting your pitches accepted?

Unless we’re pitching social games – and specifically card games – the probability of a pitch being greenlit is extremely small.

I was hearing card-based mobile games were falling out of favor, though, with Monster Strike and PazuDora being so popular.

Well, maybe I should clarify – games with “gacha” mechanics rather than just “card games.”

That means it must be really hard to pitch console games.

Indeed. Even pitches from inside major publishers are being cancelled.

Have you had any luck talking with Western publishers?

We’re not really well connected to the Western gaming scene, so that’s a bit of the challenge. We rarely even get to GDC.

So that’s why you’re going with crowdfunding for NightCry.

Well, from what I hear, it’s still also very difficult to pitch console game concepts abroad. Because this game is so unique, we thought crowdfunding would be the way to go.

Crowdfunding isn’t quite as well understood in Japan. Has this proven a challenge in terms of getting the word out about NightCry?

Actually, PR is going pretty well in Japan. The tweet that shares the promotional video was RT’ed 4000 times. But as you say, crowdfunding isn’t fully understood in Japan. The maximum amount of money you can raise in the domestic crowdfounding is probably about $20,000. Our domestic campaign has set the minimum goal around that price.

You’ve already got a mobile version of NightCry planned. What do you want to accomplish with the crowdfunded PC version that you can’t with the mobile version?

With the PC version, we’re planning on a more in-depth scenario, more playable characters… in short, the PC version would have significantly more content.

How do you feel about the current state of the horror game genre?

Well, it’s not really my place to be a reviewer for other games. Personally, though, I feel like nothing currently on the market comes close to my ideal horror game. So through this project, I’m showcasing my take on what an ideal horror game would be.

Moving forward, what is it that you most want to accomplish with NightCry?

One of the goals I have is to establish this new title as a franchise. We want to expand on this concept. If we’re able to prove that crowdfunding can work for us, I would like to create games in other genres with a solid following as well. Maybe a nice new sci-fi game!

So like an Infinite Space 2, then?

That’s right! *laughs*

What a great interview, thank you very much and congrats! He’s certainly a very interesting guy, I always think about Clock tower too. Too bad Nightcry is actually,well… Really bad! Anyway, best of luck to him!

“And now these three remain: faith, hop”e and love. But the greatest of these is love.”

Love indeed, for each other and those amazing games!